Shun the Frumious Bandersnatch?

Shun the Frumious Bandersnatch?

The Web and open source have opened up a whole new world of opportunities and services. We can search the global information storehouse, connect with our friends and make new ones, form new communities, map where stuff is, and organize and display aspects of our lives and interests as never before. These advantages compound into still newer benefits via emergent properties such as social discovery or bookmarking, adding richness to our lives that heretofore had not existed.

And all of these benefits have come for free.

Of course, as our use and sophistication of the Web and open source have grown we have come to understand that the free provision of these services is rarely (ever?) unconditional. For search, our compact is to accept ads in return for results. For social networks, our compact is give up some privacy and control of our own identities. For open source, our compact is the acceptance of (generally) little or no support and often poor documentation.

We have come to understand this quid pro quo nature of free. Where the providers of these services tend to run into problems is when they change the terms of the compact. Google, for example, might change how its search results are determined or presented or how it displays its ads. Facebook might change its privacy or data capture policies. Or, OpenOffice or MySQL might be acquired by a new provider, Oracle, that changes existing distribution, support or community involvement procedures.

Sometimes changes may fit within the acceptable parameters of the compact. But, if such changes fundamentally alter the understood compact with the user community, users may howl or vote with their feet. Depending, the service provider may relent, the users may come to accept the new changes, or the user may indeed drop the service.

The Hidden Costs of Dependence

But there is another aspect of the use of free services, the implications of which have been largely unremarked. What happens if a service we have come to depend upon is no longer available?

Abandonment or changes in service may arise from bankruptcy or a firm being acquired by another. My favorite search service of a decade ago, AltaVista, and Delicious are two prominent examples here. Existing services may be dropped by a provider or APIs removed or deprecated. For Google alone, examples include Wave and Gears, Google Labs, and many, many APIs. (The howls around Google Translate actually caused it to be restored.) And existing services may be altered, such as moving from free to fee or having capabilities significantly modified. Ning and Babbel are two examples here. There are literally thousands of examples of Web-based free services that have gone through such changes. Most have not seen widespread use, but have affected their users nonetheless.

There is nothing unique about free services in these regards. Ford was able to cease production of its Edsel and change the form factor of the Thunderbird despite some loyal fans. Sugar Pops morphed into a variety of breakfast cereal brands. Sony Betamax was beat out by VHS, which then lost out to CDs and now DVDs. My beloved Saabs are heading for the dustbin, or Chinese ownership.

In all of these cases, as consumers we have no guarantees about the permanence of the service or the infrastructure surrounding it. The provider is solely able to make these determinations. It is no different when the service or offering is free. It is the reality of the marketplace that causes such changes.

But, somehow, with free Web services, it is easy to overlook these realities. I offer a couple of personal case studies.

Case Study #1: Site Search

I have earlier described the five different versions of site search that I have gone through for this blog. The thing is, my current option, Relevanssi, is also a free plug-in. What is notable about this example, though, is the multiple attempts and (unanticipated) significant effort to discover, evaluate and then implement alternatives. Unfortunately, I rather suspect my current option may itself — because of the nature of free on the Web — need to be replaced at some time down the road.

Case Study #2: FeedBurner

Part of what caused me to abandon Google Custom Search as one of the above search options was the requirement I serve ads on my blog to use it. So, when I decided to eliminate ads entirely in 2010 I not only gave up this search option, but I also lost some of the better tracking and analytics options also provided for free by Google. Fortunately, I had also adopted FeedBurner early in the life of this blog. It was also becoming increasingly clear that feed subscribers — in addition to direct site visitors — were becoming an essential metric for gauging traffic.

I thus had a replacement means for measuring traffic trends. Google (strange how it keeps showing up!) had purchased FeedBurner in 2007, and had made some nice site and feature improvements, including turning some paid services into free. The service was performing quite well, despite FeedBurner’s infamous knack to lose certain feed counts periodically. However, this performance broke last Summer when my site statistics indicated a massive drop in subscribers.

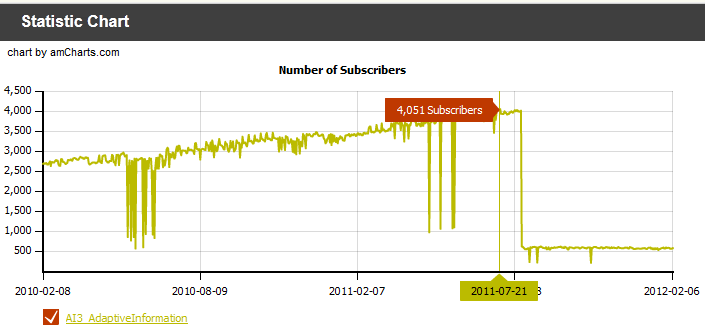

The figure below, courtesy of Feed Compare, shows the daily subscriber statistics for my AI3 blog for the past two years. The spikiness of the curve affirms the infamous statistics gaps of the service. The first part of the curve also shows nice, steady growth of readers, growing to more than 4000 by last Summer. Then, on August 16, there was a massive drop of 85% in my subscriber counts. I monitored this for a couple of days, thinking it was another temporary infamous event, then realized something more serious was afoot:

It was at this point I became active on the Google group for FeedBurner. Many others had noted the same service drop. (The major surmise is that FeedBurner now is having difficulty including Feedfetcher feeds, which is interesting because it is the feed of Google’s own Reader service, and the largest feed aggregation source on the Web.)

Over the ensuing months until last week I posted periodic notices to the official group seeking clarification as to the source of these errors and a fix to the service. In that period, no Google representative ever answered me, nor any of the numerous requests by others. I don’t believe there has been a single entry on any matter by Google staff for nearly the past year.

I made requests and inquiries no fewer than eight times over these months. True, Google had announced it was deprecating the FeedBurner API in May 2011, but, in that announcement, there was no indication that bug fixes or support to their own official group would cease. While it is completely within Google’s purview to do as it pleases, this behavior hardly lends itself to warm feelings by those using the service.

Finally, last week I dropped the FeedBurner stats and installed a replacement WordPress plugin service [1]. It was clear no fixes were forthcoming and I needed to regain an understanding of my actual subscriber base. The counts you now see on this site use this new service; they show the continuation of this site’s historical growth trend.

Is Google Becoming More Frumious?

It is not surprising that in the prior discussions Google figures prominently. It is the largest provider of APIs and free services on the Web. But, even with its continuing services, I am seeing trends that disturb me in terms of what I thought the “compact” was with the company.

I’m not liking recent changes to Google’s bread and butter, search. While they are doing much to incorporate more structure in their results, which I applaud, they are also making ranking, formatting and presentation changes I do not. I am now spending at least us much of my search time on DuckDuckGo, and have been mightily impressed with its cleanliness, quality and lack of ads in results.

I also do not like how all of my current service uses of Google are now being funneled into Google Plus. I am seeing an arrogance that Google knows what is best and wants to direct me to workflows and uses, reminiscent of the arrogance Microsoft came to assume at the height of its market share. How does that variant of Lord Acton’s dictum go? “Market share tends to corrupt, and absolute market share corrupts absolutely.”

We are seeing Google’s shift to monetize extremely popular APIs such as Maps and Translate. My company, Structured Dynamics, has utilized these services heavily for client work in the past. We now must find alternatives or cost the payment for these services into the ongoing economics of our customer installations. Of course, charging for these services is Google’s right, but it does change the equation and causes us to evaluate alternatives.

I fear that Google may be turning into a frumious Bandersnatch. I’m not sure we will shun it, but we certainly are changing our views of the basis by which we engage or not with the company and its services. Once we shift from a basis of free, our expectations as to permanence and support change as well.

Big Boys Don’t Cry

This is not a diatribe against Google nor a woe is us. Us big kids have come to know that there is no such thing as a free lunch. But that message is getting reaffirmed now more strongly in the Web context.

There can be benefits from seeking, installing or adapting to new alternatives with different service profiles when dependent services are abandoned or deprecated. Learning always takes place. Accepting one’s own responsibility for desired services also leads to control and tailoring for specific needs. Early use of free services also educates about what is desired or not, which can lead to better implementation choices if and when direct responsibility is assumed.

But, in some areas, we are seeing services or uses of the Web that we should adopt only with care or even shun. Business opportunities that depend on third-party services or APIs are very risky. Strong reliance on single-provider service ecosystems adds fragility to dependence. Own systems should be designed to not depend too strongly on specific API providers and their unique features or parameters.

Free is not forever, and it is conditional. Substitutability is a good design practice to embrace.

> I fear that Google may be turning into a frumious Bandersnatch. I’m not sure we will shun it, but we certainly are changing our views of the basis by which we engage or not with the company and its services. Once we shift from a basis of free, our expectations as to permanence and support change as well.

Nicely stated Mike and I concur

Good post!! I quietly have been becoming less dependent on Google. I understand Google is a business, but the new policy of tracking across all Google products. So recently I set DuckDuckGo as my default search engine. I will still use Google products and I’m not hating Google it’s just time to lessen my Google footprint. I wonder if more people are doing the same.