New Release Includes Manually Vetted Wikidata Mapping

New Release Includes Manually Vetted Wikidata Mapping

One of the reasons for releasing KBpedia as open source last October was the emerging usefulness of one its main constituent knowledge bases, Wikidata. Wikidata now contains about 45 million useful entities and concepts (so-called Q identifers) and more than a quarter billion data assertions across scores of languages [1]. Many of the efforts undertaken for KBpedia’s open-source release and others since then have been to increase coverage of Wikidata in KBpedia [2]. With the release of KBpedia v 2.10, we have extended the mappings to Wikidata instances to more than 98%. We also have increased coverage of other aspects of structure and properties within Wikidata to very high percentages. In this version 2.10 release we also manually inspected all 45,000 mappings of KBpedia reference concepts to Wikidata instances, resulting in many changes and improvements. The quality of mappings in KBpedia has never been higher.

KBpedia, as you recall, is a computable knowledge graph that sits astride Wikipedia and Wikidata and other leading knowledge bases. Its baseline 55,000 reference concepts provide a flexible and expandable means for relating your own data records to a common basis for reasoning and inferring logical relations and for mapping to virtually any external data source or schema. The framework is a clean starting basis for doing knowledge-based artificial intelligence (KBAI) and to train and use virtual agents. KBpedia combines seven major public knowledge bases — Wikipedia, Wikidata, schema.org, DBpedia, GeoNames, OpenCyc, and UMBEL. KBpedia supplements these core KBs with mappings to more than a score of additional leading vocabularies. The entire KBpedia structure is computable, meaning it can be reasoned over and logically sliced-and-diced to produce training sets and reference standards for machine learning and data interoperability. KBpedia provides a coherent overlay for retrieving and organizing Wikipedia or Wikidata content. KBpedia greatly reduces the time and effort traditionally required for KBAI tasks.

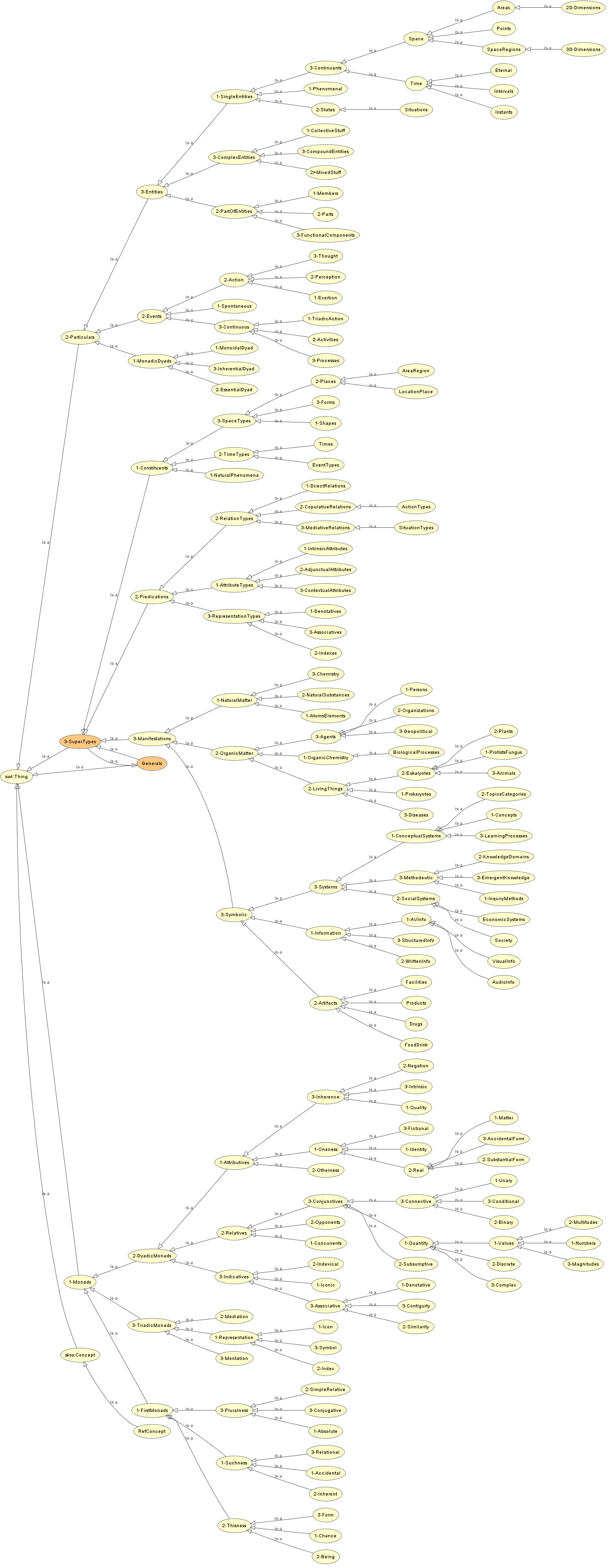

KBpedia is also a comprehensive knowledge structure for promoting data interoperability. KBpedia’s upper structure, the KBpedia Knowledge Ontology (KKO), is based on the universal categories and knowledge representation theories of the great 19th century American logician, philosopher, polymath and scientist, Charles Sanders Peirce. This design provides a logical and coherent underpinning to the entire KBpedia structure. The design is also modular and fairly straightforward to adapt to enterprise or domain purposes. KBpedia provides a powerful reference scaffolding for bringing together your own internal data stovepipes into a comprehensive whole. KBpedia, and extensions specific to your own domain needs, can be deployed incrementally, gaining benefits each step of the way, until you have a computable overlay tieing together all of your valuable information assets.

Major Activities for Version 2.10

Almost all efforts related to KBpedia v 2.10 were focused on Wikidata, though, with their close alliance, many changes also were reflected to the Wikipedia mappings. As noted with the v 2.00 release, the first effort we had was to map Q items (IDs) that have much instance coverage, but were lacking in prior mappings. This attention resulted in adding a net 973 Q IDs to KBpedia. This number is a bit misleading, however, since in the manual inspection phases many duplicates were removed from the system (approx. 2100) and earlier mappings to category Q IDs (approx. 2700) were upgraded to their more specific Q ID instance. Thus, nearly 6,000 Q IDs are now different in this version compared to the prior version 2.00. Since many of the Q IDs also have a direct mapping to a Wikipedia counterpart, these mappings were updated as well. Besides incidental improvements to definitions, linkages and labels that arise when doing such inspections, which were also attended to whenever encountered, no further major changes were made to this newest release.

We are now in very good shape with respect to our mapping and coverage of Wikidata (with a similar profile for Wikipedia). Across a breadth of measures, here is now where we stand with respect to Wikidata coverage [3], with implementation notes provided in the endnotes section:

| Wikidata Item |

No. Items |

No. Mapped Items |

Coverage |

[3] |

| Q IDs |

45,306,576 |

45,882 |

00.1% |

[4] |

| Q instances |

45,306,576 |

44,458,015 |

98.1% |

[4] |

| Q classes |

2,493,795 |

2,312,116 |

92.7% |

[5] |

| Properties |

5,910 |

3,970 |

67.2% |

[6] |

| P Statements |

256,298,963 |

246,055,199 |

96.0% |

[7] |

| P Qualifiers |

38,866,255 |

31,756,937 |

81.7% |

[7,8] |

| P References |

24,582,259 |

20,121,794 |

81.9% |

[7,9] |

One of the first observations that jumps out of the table is how relatively few mappings (~ 45 K, or 0.1%) are sufficient to capture nearly all (98%) of the instances contained in Wikidata. This is because a Q ID may be an individual instance or a parent to multiple instances. The KBpedia mappings focus on the parents, through which the individual instances may be obtained. By virtue of the additions and Q mapping improvements in this version, KBpedia has expanded its instance reach from about 30 million entities to now 45 million entities.

Another observation is that we are also capturing a significant portion of the structure of Wikidata (93%) as provided by the mappings to Q IDs with significant subClassOf connections (P279), which is where the taxonomy of the knowledge base is defined. A third summary observation is that we have similarly high levels of coverage to Wikidata properties. However, at present, this is the least developed area of KBpedia with respect to use cases or cross-knowledge base mappings.

A minor change, but useful to the KBpedia Web site, has been our downgrading of the OpenCyc and UMBEL mapped items. They are still mapped in the knowledge structure, but the Web site removes their links in order to highlight the most popular knowledge bases.

Despite these upgrades and enhancements, the coverage of KBpedia in my new book, A Knowledge Representation Practionary: Guidelines Based on Charles Sanders Peirce (Springer), remains current. The book emphasizes theory, architecture and design, which remains unchanged in this current new release of KBpedia. Also note that future areas of improvement were listed in the KBpedia v 2.00 release notice.

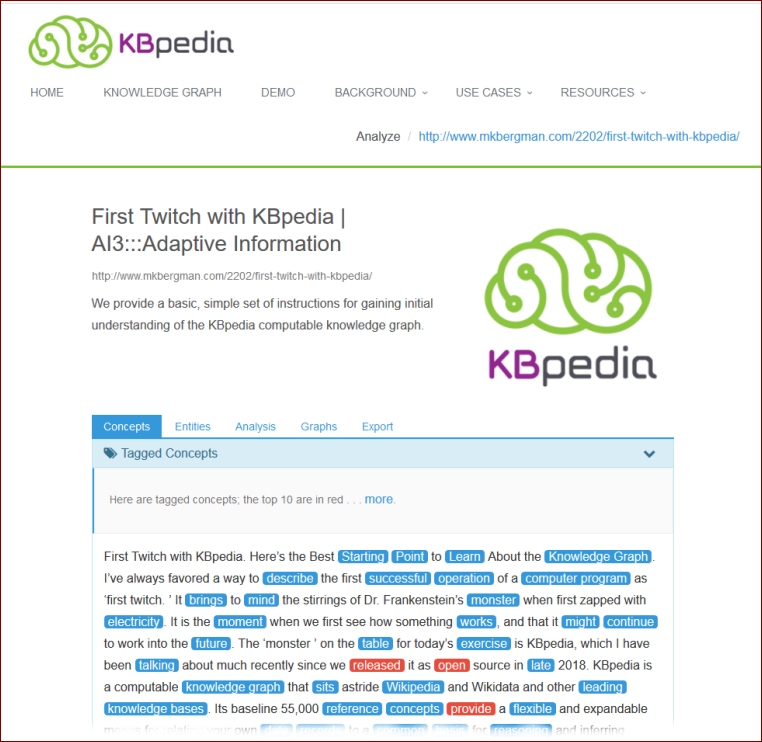

Getting the System

The KBpedia Web site provides a working KBpedia explorer and demo of how the system may be applied to local content for tagging or analysis. KBpedia splits between entities and concepts, on the one hand, and splits in predicates based on attributes, external relations, and pointers or indexes, all informed by Charles Peirce’s prescient theories of knowledge representation.

Mappings to all external sources are provided in the linkages to the external resources file in the KBpedia downloads. (A larger inferred version is also available.) The external sources keep their own record files. KBpedia distributions provide the links. However, you can access these entities through the KBpedia explorer on the project’s Web site (see these entity examples for cameras, cakes, and canyons; clicking on any of the individual entity links will bring up the full instance record. Such reach-throughs are straightforward to construct.)

Here are the various KBpedia resources that you may download or use for free with attribution:

- The complete KBpedia v 210 knowledge graph (8.5 MB, zipped). This download is likely your most useful starting point

- KBpedia’s upper ontology, KKO (332 KB), which is easily inspected and navigated in an editor

- The annotated KKO (321 KB). This is NOT an active ontology, but is has the upper concepts annotated to more clearly show the Peircean categories of Firstness (1ns), Secondness (2ns), and Thirdness (3ns)

- The 68 individual KBpedia typologies in N3 format

- The KBpedia mappings to the seven core knowledge bases and the additional extended knowledge bases in N3 format

- A version of the full KBpedia knowledge graph extended with linkages to the external resources (10.5 MB, zipped), and

- A version of the full KBpedia knowledge graph extended with inferences and linkages (14.7 MB, zipped).

The last two resources require time and sufficient memory to load. We invite and welcome contributions or commentary on any of these resources.

All resources are available under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license. KBpedia’s development to date has been sponsored by Cognonto Corporation. We welcome suggestions for further enhancements or tackling your own improvements. Please let me know what ideas you may have.

Notes

[1] Useful mappings exclude mappings to internal Wikimedia sources (such as templates, categories, or infoboxes on Wikipedia and Wikidata) and scholarly articles (linked in other manners). There are about 45 million ‘useful’ records in the current Wikipedia based on these filters.

[2] ‘Coverage’ is understood to be the percentage of useful instances in a source knowledge base to KBpedia that are actually mapped to a specific KBpedia reference concept or property. These source instances are not included in the KBpedia distribution. They are accessed from the source knowledge base directly. Manipulation of the KBpedia knowledge graph results in the identification of this external source data.

[3] The number of items shown for Wikidata does not reflect the total items on the service, but only those that are useful and relevant after administrative categories and such are removed.

[4] See the text where we describe how choosing to map appropriate structural nodes in Wikidata, which themselves have many child instances, leads to large percentage coverage of all available instances. Instance relationships are obtained from the

P31 Wikidata property. The Q IDs were obtained from a Feb 19, 2019 Wikidata retrieval.

[5] Like the instance (P31) retrievals, the

subClassOf (P279) data was obtained by a SPARQL query to the Wikidata query endpoint.

Try it![6] The properties data was obtained from the

SQID Wikidata service on April 4, 2019. Note, if you try this link, be patient for all of the data to load.

[7] A Wikidata

statement pairs a property with a value for a given entity. It is equivalent to an assertion. It is the most basic factual statement in Wikidata.

[8] Wikidata

qualifiers allow statements to be expanded on, annotated, or contextualized beyond what can be expressed in just a simple property-value pair.

[9] Wikidata

references are used to point to specific sources that back up the data provided in a statement.

It’s Worked for Me, But is Not for Everyone

It’s Worked for Me, But is Not for Everyone