Was the Industrial Revolution Truly the Catalyst?

Was the Industrial Revolution Truly the Catalyst?

Why, roughly beginning in 1820, did historical economic growth patterns skyrocket?

This is a question of no small import, and one that has occupied economic historians for many decades. We know what some of the major transitions have been in recorded history: the printing press, Renaissance, Age of Reason, Reformation, scientific method, Industrial Revolution, and so forth. But, which of these factors were outcomes, and which were causative?

This is not a new topic for me. Some of my earlier posts have discussed Paul Ormerod’s Why Most Things Fail: Evolution, Extinction and Economics, David Warsh’s Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations: A Story of Economic Discovery, David M. Levy’s Scrolling Forward: Making Sense of Documents in the Digital Age, Elizabeth Eisenstein’s classic Printing Press, Joel Mokyr’s Gifts of Athena : Historical Origins of the Knowledge Economy, Daniel R. Headrick’s When Information Came of Age : Technologies of Knowledge in the Age of Reason and Revolution, 1700-1850, and Yochai Benkler’s, The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedoms. Thought provoking references, all.

But, in my opinion, none of them posits the central point.

Statistical Leaps of Faith

Statistics (originally derived from the concept of information about the state) really only began to be collected in France in the 1700s. For example, the first true population census (as opposed to the enumerations of biblical times) occurred in Spain in that same century, with the United States being the first country to set forth a decennial census beginning around 1790. Pretty much everything of a quantitative historical basis prior to that point is a guesstimate, and often a lousy one to boot.

Because no data was collected — indeed, the idea of data and statistics did not exist — attempts in our modern times to re-create economic and population assessments in earlier centuries are truly a heroic — and an estimation-laden exercise. Nonetheless, the renowned economic historian who has written a number of definitive OECD studies, Angus Maddison, and his team have prepared economic and population growth estimates for the world and various regions going back to AD 1 [1].

One summary of their results shows:

| Year | Ave Per Capita | Ave Annual | Yrs Required |

| AD | GDP (1990 $) | Growth Rate | for Doubling |

| 1 | 461 | ||

| 1000 | 450 | -0.002% | N/A |

| 1500 | 566 | 0.046% | 1,504 |

| 1600 | 596 | 0.051% | 1,365 |

| 1700 | 615 | 0.032% | 2,167 |

| 1820 | 667 | 0.067% | 1,036 |

| 1870 | 874 | 0.542% | 128 |

| 1900 | 1,262 | 1.235% | 56 |

| 1913 | 1,526 | 1.470% | 47 |

| 1950 | 2,111 | 0.881% | 79 |

| 1967 | 3,396 | 2.836% | 25 |

| 1985 | 4,764 | 1.898% | 37 |

| 2003 | 6,432 | 1.682% | 42 |

Note that through at least 1000 AD economic growth per capita (as well as population growth) was approximately flat. Indeed, up to the nineteenth century, Maddison estimates that a doubling of economic well-being per capita only occurred every 3000 to 4000 years. But, by 1820 or so onward, this doubling accelerated at warp speed to every 50 years or so.

Looking at a Couple of Historical Breakpoints

The first historical shift in millenial trends occurred roughly about 1000 AD, when flat or negative growth began to accelerate slightly. The growth trend looks comparatively impressive in the figure below, but that is only because the doubling of economic per capita wealth has now dropped to about every 1000 to 2000 years (note the relatively small differences in the income scale). These are annual growth rates about 30 times lower than today, which, with compounding, prove anemic indeed (see estimated rates in the table above).

Nonetheless, at about 1000 AD, however, there is an inflection point, though small. It is also one that corresponds somewhat to the adoption of raw linen paper v. skins and vellum (among other correlations that might be drawn).

When the economic growth scale gets expanded to include today, these optics change considerable. Yes, there was a bit of growth inflection around 1000 AD, but it is almost lost in the noise over the longer historical horizon. The real discontinuity in economic growth appears to have occurred in the early 1800s compared to all previous recorded history. At this major inflection point in the early 1800s, historically flat income averages skyrocketed. Why?

The fact that this inflection point does not correspond to earlier events such as invention of the printing press or Reformation (or other earlier notable transitions) — and does more closely correspond to the era of the Industrial Revolution — has tended to cement in popular histories and the public’s mind that it was machinery and mechanization that was the causative factor creating economic growth.

Had a notable transition occurred in the mid-1400s to 1500s it would have been obvious to ascribe more modern economic growth trends with the availability of information and the printing press. And, while, indeed, the printing press had massive effects, as Elizabeth Eisenstein has shown, the empirical record of changes in economic growth is not directly linked with adoption of the printing press. Moreover, as the graph above shows, something huge did happen in the early 1800s.

Pulp Paper and Mass Media

In its earliest incarnations, the printing press was an instrument of broader idea dissemination, but still largely to and through a relatively small and elite educated class. That is because books and printed material were still too expensive — I would submit largely due to the exorbitant cost of paper — even though somewhat more available to the wealthy classes. Ideas were fermenting, but the relative percentage of participants in that direct ferment were small. The overall situation was better than monks laboriously scribing manuscripts, but not disruptively so.

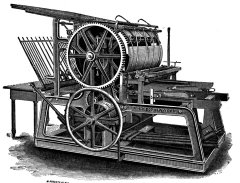

However, by the 1800s, those base conditions change, as reflected in the figure above. The combination of mechanical presses and paper production with the innovation of cheaper “pulp” paper were the factors that truly brought information to the “masses.” Yet, some have even taken “mass media” to be its own pejorative. But, look closely as what that term means and its importance to bringing information to the broader populace.

In Paul Starr’s Creation of the Media, he notes how in 15 years from 1835 to 1850 the cost of setting up a mass-circulation paper increased from $10,000 to over $2 million (in 2005 dollars). True, mechanization was increasing costs, but from the standpoint of consumers, the cost of information content was dropping to zero and approaching a near-time immediacy. The concept of “news” was coined, delivered by the “press” for a now-emerging “mass media.” Hmmm.

This mass publishing and pulp paper were emerging to bring an increasing storehouse of content and information to the public at levels never before seen. Though mass media may prove to be an historical artifact, its role in bringing literacy and information to the “masses” was generally an unalloyed good and the basis for an improvement in economic well being the likes of which had never been seen.

More recent trends show an upward blip in growth shortly after the turn of the 20th century, corresponding to electrification, but then a much larger discontinuity beginning after World War II:

In keeping with my thesis, I would posit that organizational information efforts and early electromechanical and then electronic computers resulting from the war effort, which in turn led to more efficient processing of information, were possible factors for this post-WWII growth increase.

It is silly, of course, to point to single factors or offer simplistic slogans about why this growth occurred and when. Indeed, the scientific revolution, industrial revolution, increase in literacy, electrification, printing press, Reformation, rise in democracy, and many other plausible and worthy candidates have been brought forward to explain these historical inflections in accelerated growth. For my own lights, I believe each and every one of these factors had its role to play.

But at a more fundamental level, I believe the drivers for this growth change came from the global increase and access to prior human information. Surely, the printing press helped to increase absolute volumes. Declining paper costs (a factor I believe to be greatly overlooked but also conterminous with the growth spurt and the transition from rag to pulp paper in the early 1800s), made information access affordable and universal. With accumulations in information volume came the need for better means to organize and present that information — title pages, tables of contents, indexes, glossaries, encyclopedia, dictionaries, journals, logs, ledgers,etc., all innovations of relatively recent times — that themselves worked to further fuel growth and development.

Of course, were I an economic historian, I would need to argue and document my thesis in a 400-pp book. And, even then, my arguments would appropriately be subject to debate and scrutiny.

Information, Not Machines

Tools and physical artifacts distinguish us from other animals. When we see the lack of a direct correlation of growth changes with the invention of the printing press, or growth changes approximate to the age of machines corresponding to the Industrial Revolution, it is easy and natural for us humans to equate such things to the tangible device. Indeed, our current fixation on technology is in part due to our comfort as tool makers. But, is this association with the technology and the tangible reliable, or (hehe) “artifactual”?

Information, specifically non-biological information passed on through cultural means, is what truly distinguishes us humans from other animals. We have been easily distracted looking at the tangible, when it is the information artifacts (“symbols”) that make us the humans who we truly are.

So, the confluence of cheaper machines (steam printing presses) with cheaper paper (pulp) brought information to the masses. And, in that process, more people learned, more people shared, and more people could innovate. And, yes, folks, we innovated like hell, and continue to do so today.

If the nature of the biological organism is to contain within it genetic information from which adaptations arise that it can pass to offspring via reproduction — an information volume that is inherently limited and only transmittable by single organisms — then the nature of human cultural information is a massive shift to an entirely different plane.

With the fixity and permanence of printing and cheap paper — and now cheap electrons — all prior discovered information across the entire species can now be accumulated and passed on to subsequent generations. Our storehouse of available information is thus accreting in an exponential way, and available to all. These factors make the fitness of our species a truly quantum shift from all prior biological beings, including early humans.

What Now Internet?

The information by which the means to produce and disseminate information itself is changing and growing. This is an infrastructural innovation that applies multiplier benefits upon the standard multiplier benefit of information. In other words, innovation in the basis of information use and dissemination itself is disruptive. Over history, writing systems, paper, the printing press, mass paper, and electronic information have all had such multiplier effects.

The Internet is but the latest example of such innovations in the infrastructural groundings of information. The Internet will continue to support the inexorable trend to more adaptability, more wealth and more participation. The multiplier effect of information itself will continue to empower and strengthen the individual, not in spite of mass media or any other ideologically based viewpoint but due to the freeing and adaptive benefits of information itself. Information is the natural antidote to entropy and, longer term, to the concentrations of wealth and power.

If many of these arguments of the importance of the availability of information prove correct, then we should conclude that the phenomenon of the Internet and global information access promises still more benefits to come. We are truly seeing access to meaningful information leapfrog anything seen before in history, with soon nearly every person on Earth contributing to the information dialog and leverage.

Endnote: And, oh, to answer the rhetorical question of this piece: No, it is information that has been the source of economic growth. The Industrial Revolution was but a natural expression of then-current information and through its innovations a source of still newer-information, all continuing to feed economic growth.

[1] The historical data were originally developed in three books by Angus Maddison: Monitoring the World Economy 1820-1992, OECD, Paris 1995; The World Economy: A Millennial Perspective, OECD Development Centre, Paris 2001; and The World Economy: Historical Statistics, OECD Development Centre, Paris 2003. All these contain detailed source notes. Figures for 1820 onwards are annual, wherever possible.

For earlier years, benchmark figures are shown for 1 AD, 1000 AD, 1500, 1600 and 1700. These figures have been updated to 2003 and may be downloaded by spreadsheet from the Groningen Growth and Development Centre (GGDC), a research group of economists and economic historians at the Economics Department of the University of Groningen headed by Maddison. See http://www.ggdc.net/.

Michael,

First of all, thanks for writing so prolifically about the Semantic Web in your blog. Not only have I enjoyed following your journey, I always learned something along the way.

In regard to this recent post, I could not agree more with your postulating about the reality of those key inflection points on the graph. You write within the context of the macro economic picture over the long term. I would posit to you that there is the analog when one applies the same thinking to the corporate world. Unfortunately, over the course of my consulting career I formed the opinion that IT today is very much undervalued by people running businesses. Perhaps it is attitudes that have to change first before a firm can realize similar exponential growth from information. In my experience every once in awhile smaller firms seem to be able to execute on information and knowledge of actionable intelligence better because they are more agile, lean and highly competitive. When I started my career in 1972 attitudes were much different. I think they started changing for the worse with dawn of the PC Computer to the masses.

In the larger corporate scenes people seem to think the IT/IS stuff is simply a necessary evil. And in fact where I work, many people will not use their email believe it or not. If IT or the management of knowledge was important enough for executives in their annual strategic planning, they would not outsource which in my opinion further devalues the net worth of a firms information assets. It is not a matter of saving labor costs on programmers. Your subject matter experts, engineers, scientists all reside within your organization and they are the people who will construct ontologies or design systems around manufacturing and processes. I am not certain you can ever commoditize these attributes because these are the vectors of innovation within our own business and knowledge domains.

The entire IT organization in many firms are staffed with generalists and they have no hope of developing data and information into useful knowledge assets as we think of them in the Semantic Web setting. Take for instance Pharma firms, the biggest percentage of them are not producing cutting edge knowledge management tools, systems, ontologies, etc. that anybody would write home about. Maybe I live a shelterd life, but I certainly have not found this to be the case where I work. Most of this cutting edge technology as you know is blooming from many of our academic institutions. See

http://www.ispe.org/page.ww?section=Journal+of+Pharmaceutical+Innovation&name=Toward+intelligent+decision+support+for+pharmaceutical+product+development

If what you are saying about the real driver of economic growth is human knowledge leading to innovation, a corporation if ever there comes a day of maturity about going from being an IT or MIS mentality to capitalizing on knowledge, only then will we see exceptional economic performances from the large corporate entities which will translate into the macro picture and another blip on the graph. In the meantime, we are stagnated with a host of applications in the pharma area such as LIMS, Trackwise, SAP, eDoc, eRoom to name a few that are so Semantic unfriendly toward the very concepts you elicit in your writings. We exchange unstructured documents, emails, and chase distributed data to the point where it is getting very difficult to develop a new product, manufacture under licensure and bring it to market at reasonable prices. I will get off my minor musical chord now.

Anyway, great article! Keep up the good work.

Kind Regards,

John Wubbel

Hi John,

Thank you so much for your thoughtful comments. What was that paraphrased sentiment: Life sucks and then you die?!

Actually, seriously ….

Let me know if you post something longer on your own blog or elsewhere on this topic. In general, I think the institution of the “corporation” deserves inspection in its own right, and we may also be passing its zenith as an organizational mode for human activity.

I’ve been working virtually now since 1988 (19 years!), which labelled me in the early years as a “teleworker” or “telecommuter” or “unusual” (I actually was invited to speak at numerous conferences years ago on what it was like to work from home!) (all of which meant I was ill suited for the corporate life in any case!).

I now see ads for jobs touting virtual and global and the rest. So, perhaps some of your concerns about the “corporate” may be temporal and liable to similar massive shifts as in past history, which after some indigestion have often proved generally to the good.

Keep in touch, Mike