Bringing Knowledge Graphs into the Content Workflow

The rationale for starting this Cooking with Python and KBpedia series is to better match knowledge graph creation and use with practical requirements and workflows. The notion of ‘roundtripping‘ has one major use when bulk changes are needed, such as making modifications to the domain or scope of the knowledge graph. But roundtripping also supports the idea of a knowledge graph as a computable object, not simply an editable one.

Think for a moment about this: your organization has a vetted knowledge graph at the center of many analytic and knowledge management functions. How does one grow and extend such a resource, while also being able to make bulk changes or have it operate as a constantly available schema? On the one hand, such a vision requires a dynamic, always-on resource that is subject to constant querying and modification. On the other hand, this vision also means staff extending and maintaining the knowledge graph according to organizational standards and governance. The versions of the artifact may differ at various stages when these two hands work together. The capabilities needed to support a roundtripping capability are also some of the same ones needed to support these twin dynamic and standard roles. At some points we work directly with the artifact as a standalone thing, extending it and testing it for consistency and logic. At some points, the current production version of the knowledge graph is being actively exercised for knowledge management, data analysis, data integration, machine learning, or natural language processing tasks.

Now that we have put in place a framework for bulk changes and roundtripping, we next need to turn our attention to how we can access and use that knowledge artifact in a dynamic way. Such serious deployments of knowledge graphs imply many other things in version control, version deployments, and release governance. Those are topics outside of our series on the cowpoke Python package. But dynamic access and use of the knowledge graph is not outside of that scope.

How we may approach this issue in relation to workflows and HTML widgets that we may deploy directly to knowledge workers in a distributed manner is the topic of today’s CWPK installment. Our next installment with then showcase a few code examples of these widgets. Note we will also return to this topic in CWPK #58 onward when we also discuss how to publish results from our knowledge graphs to the Web.

Let’s First Consider Workflows

If your interests at this point are simply in learning a bit more about knowledge graphs (KGs), and perhaps how to design and build them, you may want to set today’s and tomorrow’s installments aside until another day. But, assuming that your interest in knowledge graphs is for eventual productive use within your organization, you will need to grapple at some point with how to integrate KGs into your staff’s current activities and how KGs may contribute to new capabilities.

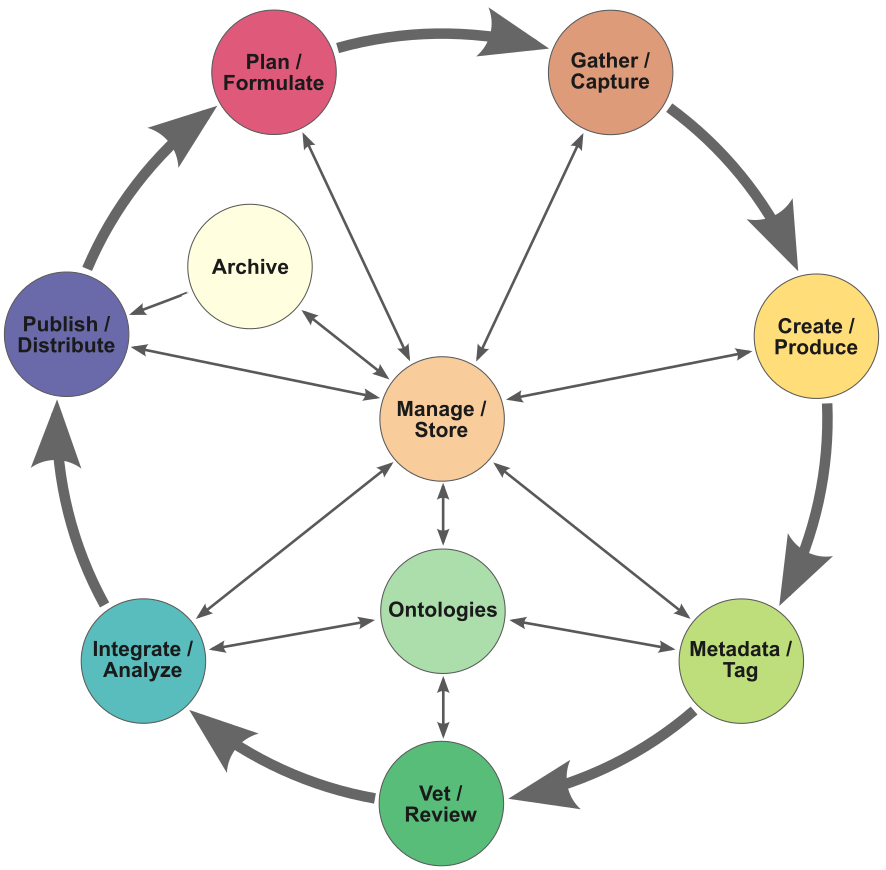

There are clearly many ways to look at content workflows, but here is our longstanding view of knowledge graphs (ontologies) and content management for what might occur in a ‘typical’ larger organization:

Starting at the center, we can understand the Manage/Store bubble to represent what we have in owlready2 (or any similarly hosted knowledge graph). That central hub (which might be a different deployment version) can be the target for gathering activities, creating, tagging, analyzing, managing knowledge, publishing or planning. A separate Ontologies bubble may be the source for bulk updates or changes or for reviewing submissions prior to committing to the central, deployed hub. Older hubs or retired versions may be shifted to an archive status.

There could be different stages and names for these basic activities, and one might also use an ontology to actually govern and provide the ‘tags’ for tracking where content stands. (Including such things as sign-offs.) But, this circle, in general, represents a common set of uses to which any organization would likely aspire. These steps can be expanded or collapsed as local circumstances dictate.

What is important to note, however, is that most activities around the circumference of the workflow occur in context with other existing activities. For example, when reviewing Internet search results or creating documents, both tagging of new content or updating the existing knowledge base would be made easier by having small plug-ins or widgets for the existing applications. Machine learning and statistical tests, or natural language applications, may all surface possible inconsistencies in an existing knowledge graph, which is best captured immediately in conjunction with the tests.

What emerges when inspecting opportunity or choke points for using knowledge graphs is that in nearly all cases new knowledge discoveries occur in conjunction with existing work activities, and if not captured immediately and easily, are all too often not recorded. This inability to capture knowledge in real time undercuts the usefulness of knowledge management and causes existing knowledge to go stale.

For these reasons, it makes sense to assemble a suite of widgets that may conduct simple activities against the knowledge graph, and can be embedded in HTML pages for interacting with current applications. Of course, the nature of the widget and what it does is dependent on the specific current activity at-hand. But these simple activities all tend to be one of the CRUD activities (create – read – update – delete) and are quite patterned.

Python Web Frameworks and Related

The reasons for me to choose Python as the basis for this CWPK series was based on data science applications with a broad user base and an abundance of useful packages and libraries. The usefulness of Python to Web page or site development was not an initial consideration.

Our own experience with Web site development, which as been extensive over the years, began with PHP and eventually migrated into the more modern JavaScript approaches like Bootstrap, our current preferred basis. Sometimes we have created intimate relationships with CMS systems, most prominently Drupal, though we have moved away from such monolithic frameworks to the more fluid ones like Bootstrap.

However, I have been quite impressed working with Jupyter Notebook and have also been following certain Web framework Python packages. Prominent ones that have impressed me (though for very different reasons) include Flask, Tornado, Flexx, Pyramid, Bottle and CherryPy. Useful supporting packages and libraries include Requests and WSGI.

My first thought about this part of the CWPK series was to pick one of these frameworks, learn some rudimentary things with it sufficient to support our widget orientation, and then use it consistently for all HTML aspects. Were I to make that decision, Flask would be my choice based on what I have studied. But I am not now choosing to move in that direction, for a number of reasons.

First, it is difficult to demo Web interactions when it it unlikely that some in the audience may not be readily able to set up their own Web sites. Second, a distributed work environment relies on many existing applications. Even if all of these use HTML interfaces in some manner, it is likely that an effective deployment would still require perhaps multiple frameworks and integrations. Third, though I could set up a dedicated demo site, that would still require adopting a full Web framework with socket, authentication, and content negotiation support. In an ultimate deployment, that is a likely step that must be taken, but our job right now is not to prototype a production system. And, fourth, the easiest way to showcase dynamic demos is to piggyback on what we already have installed and are using: Jupyter Notebook.

Fortunately, there is a nice library of widgets useful in Jupyter Notebook, the ipywidget package, and additional third-party extensions. Widgets are objects that have familiar user interfaces that may be embedded in an HTML page. Example widgets include textboxes, radiobuttons, regular buttons, dropdown lists, tabular displays, graph plots or charts, slider controls, or other forms for interacting with a Web page and its data. Dashboards, for example, are often a built-up combination of multiple widgets. Widgets are common to all modern languages used on the Web, though how they are set up and controlled varies widely.

Because we could relatively demo these widget capabilities directly through Notebook without much further complexity, and have that work in other user settings, we decided to go with the ipywidget option. We will install and demo some Flask uses in about ten installments from now. But, for our current interests in tieing our knowledge graphs to existing work activities, we introduce code for some exemplar widgets in our next CWPK installment.

Additional Documentation

Here are some background materials on the Web frameworks in Python that may be of some use to you:

- The Requests package, and many supporting documents and tutorials

- Material on Flask, including mega tutorials and other supporting materials

- General background material on Python Webframeworks.

*.ipynb file. It may take a bit of time for the interactive option to load.