Events are a Quasi-Entity and Cross All of Peirce’s Universal Categories

Events are a Quasi-Entity and Cross All of Peirce’s Universal Categories

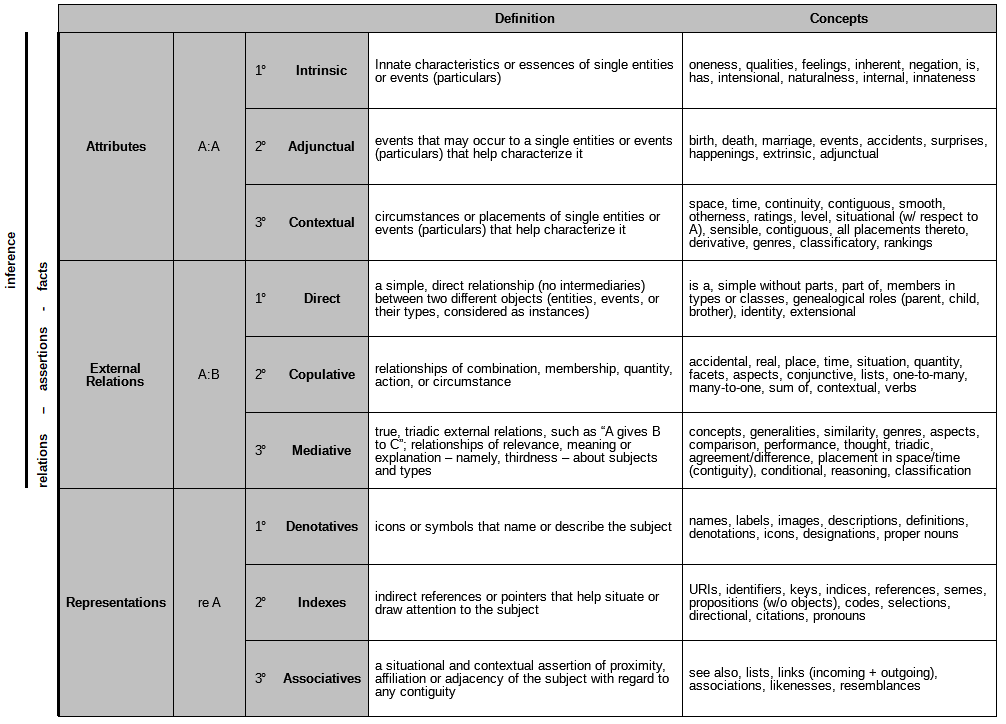

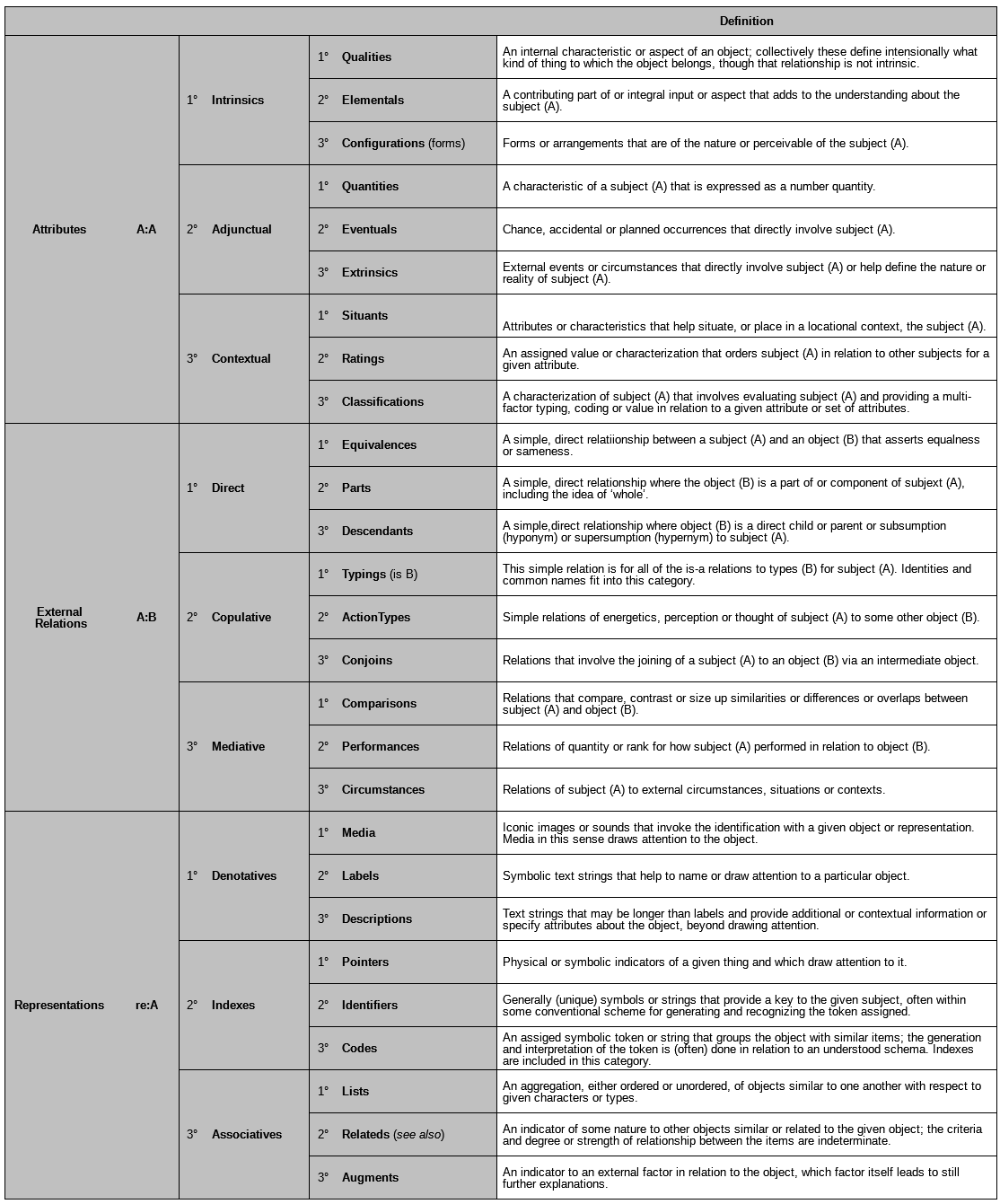

Most knowledge graphs have an orientation to things and concepts, what might be called the nouns of the knowledge space. Entities and concepts have certainly occupied my own attention in my work on the UMBEL and KBpedia ontologies over the past decade. In Part I of this series, I discussed how knowledge graphs, or ontologies, needed to move beyond simple representations of things to embrace how those things actually interact in the world, which is the understanding of context. What I discuss in this part is how one might see actions and events in a way that has logic and coherency. What I discuss in this part is an event-action model.

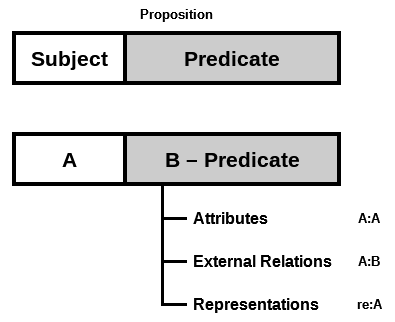

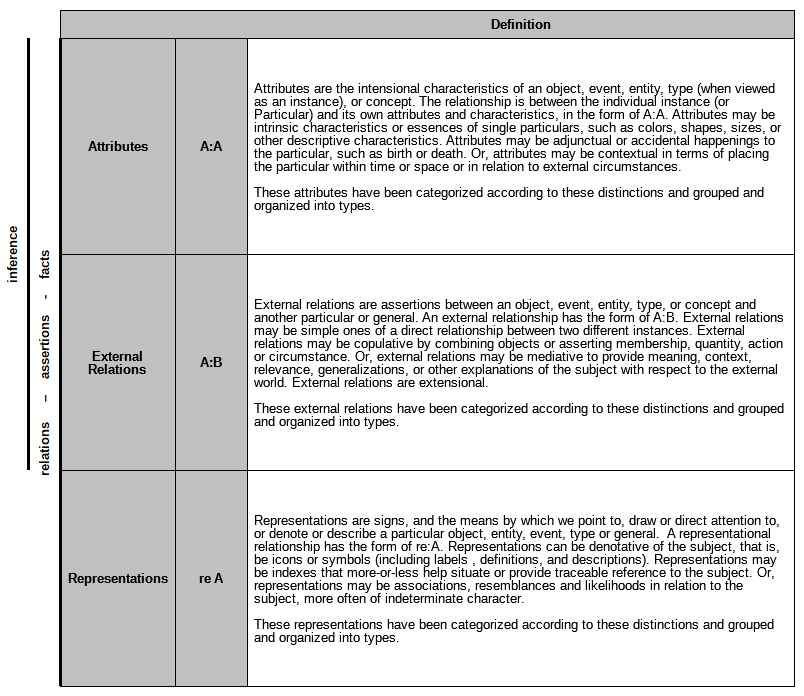

As we all know, knowledge statements or assertions are propositions that combine a subject with a predicate. Those predicates might describe the nature or character of the subject or might relate the subject to other objects or situations. For covering this aspect we need to pay close attention to the verbs or relations that connect these things.

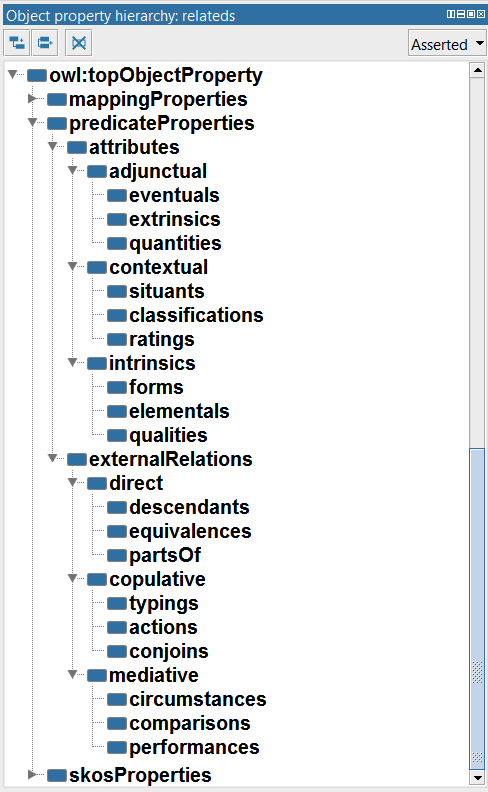

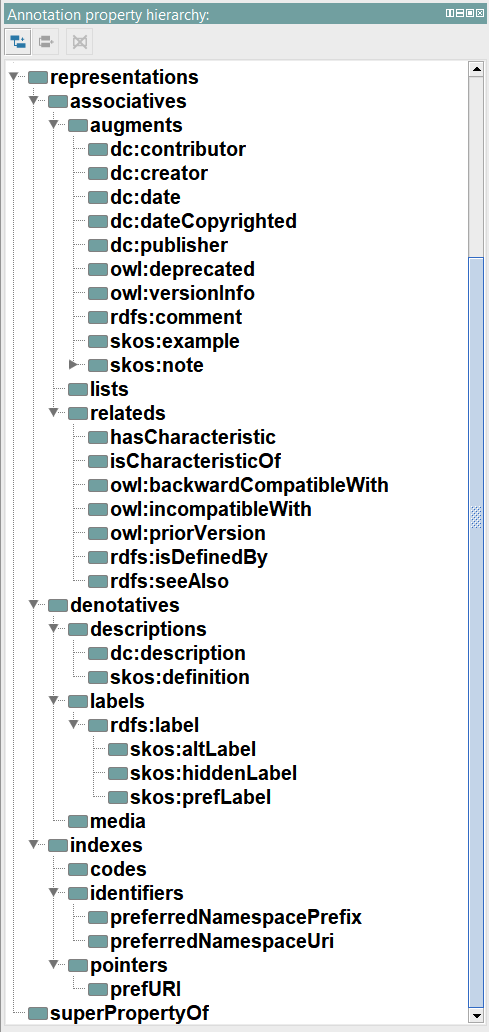

How we model or represent these things is one of the critical design choices in a knowledge graph. But these choices go beyond simply using RDF or OWL properties (or whatever predicate basis your modeling language may provide). Modeling relations and predicates needs to capture a worldview of how things are connected, preferably based on some coherent, underlying rationale. Similar to how we categorize the things and entities in our world, we also need to make ontological choices (in the classic sense of the Greek ontos, or the nature of being) as to what a predicate is and how predicates may be classified and organized. As I noted in Part I, much less is discussed about this topic in the literature.

Some Things Just Take Time

Information and information theory have been my passion my entire professional career. In that period, two questions stand out as the most perplexing to me, each of which took some years to resolve to some level of personal intellectual satisfaction. My first perplexing question was how to place information in text on to a common, equal basis to the information in a database, such as a structured record. (Yeah, I know, kind of a weird question.) These ruminations, now what we call being able to place unstructured, semi-structured and structured information on to a common footing, was finally solved for me by the RDF (Resource Description Framework) data model. But, prior to RDF, and for perhaps a decade or more, I thought long and hard and read much on this question. I’m sure there were other data models out there at the time that could have perhaps given me the way forward, but I did not discover them. It took RDF and its basic subject-predicate-object (s-p-o) triple assertion to show me the way forward. It was not only a light going on once I understood, but the opening of a door to a whole new world of thinking about knowledge representation.

My second question is one that has been gnawing at me for at least five or six years. The question is, What is an event? (Yeah, I know, another kind of weird question.) When one starts representing information in a knowledge graph, we model things. My early ideas of what is an entity is that it was some form of nameable thing. By that light, the War of 1812, or a heartbeat, or an Industrial Age are all entities. But these things are events, granted of greatly varying length, that are somehow different from tangible objects that we can see or sense in the world, and different from ideas or thoughts. These things all differ, but how and why?

Actually, the splits noted in the prior paragraph give us this clue. Events are part of time, occupy some length of time, and sometimes are so notable as to get their own names, either as types or named events. They have no substance or tangibility. These characteristics are surely different than tangible objects which occupy some space, have physicality, exist over some length of time, and also get their own names as types or named instances. And both of these are different still than concepts or ideas that are creatures of thought.

These distinctions, mostly first sensed or intuited, are hard to think about because we need a vocabulary and mindset (context) by which to evaluate and discern believable differences. For me, the idea and definition of What is an event? was my focus and entry point to try to probe this question. Somehow, I felt events to be a key to the very structures used for knowledge representation (KR) or knowledge-based artificial intelligence (KBAI), which need to be governed by some form of conceptual schema. In the semantic Web space, such schema are known as “ontologies”, since they attempt to capture the nature or being (Greek ὄντως, or ontós) of the knowledge domain at hand. Because the word ‘ontology’ is a bit intimidating, a better variant has proven to be the knowledge graph (because all semantic ontologies take the structural form of a graph). In Cognonto‘s KBAI efforts, we tend to use the terms ontology and knowledge graph interchangeably.

A key guide to this question of What is an event? are the views of Charles Sanders Peirce, the great 19th century American logician, polymath and philosopher. His theory of the universal categories — what he termed Firstness, Secondness and Thirdness — provides the groundings for his views on logic and sign-making. As we’ve noted before about KBpedia, Peirce’s theory of universal categories greatly informs how we have constructed it [1]. Peirce’s categories, while unique, are an organizational framework not unlike categories of being put forward by many philosophers; see [1] for more background on this topic.

Thus, with liberal quotes from Peirce himself [2], I work through below some of the background context for how we treat events — and related topics such as actions, relations, situations and predicates — in our pending KBpedia v 150 release.

What is an Event?

Of course, I am hardly raising new questions. The philosophical question of What is an event? is readily traced back to Plato and Aristotle. The fact we have no real intellectual consensus as to What is an event? after 2500 years suggests both that it is a good question, but also that any “answer” is unlikely to find consensus. Nonetheless, I think through the application of Peircean principles we can still find a formulation that is coherent and logically consistent (and, thus, computable).

To begin this evaluation, let’s first summarize the diversity of views of What is an event? Given the long history of this question, and the voluminous writings and diversity of opinion on the matter, a good place to start is the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, which offers a kind of Cliff Notes version overviewing various views on events [3], among many other articles in philosophy. I encourage interested students of this question to study that entry in detail. However, we can summarize the various views as fitting into one or more of these definitions:

- Events are objects (also potentially referred to as entities)

- Events are facts

- Events are actions

- Events are properties

- Events are times

- Events are situations.

Within the context of current knowledge bases, the Cyc knowledge base, for example, asserts situations are a generalization of events, and actions are a specialization of events. Most current semantic Web ontologies place events in the same category or class as entities. Some upper ontologies model time in a different way by viewing objects as temporal parts that change over time, or other dichotomous splits around the questions of events and actions. Like I said, there is really no consensus model for events and actually little discussion of them.

From our use in general language, I think we can fairly define events as having some of these characteristics:

- Events occur in time; “For example, everyday experience is that events occur in time, and that time has but one dimension.” (CP 1.273)

- Events have a beginning, duration and end

- Events may be of nearly instantaneous duration (beta decay) to periods spanning centuries or millenia (the Industrial Age, the Cenozoic Era)

- Events can refer to individual instances (tokens in Peircean terms) or general types

- Events may be single or recurring (birthdays)

- Events occur, or “take place”

- Events, if sufficiently notable, can be properly named (World War II).

For Peirce, “We perceive objects brought before us; but that which we especially experience — the kind of thing to which the word ‘experience’ is more particularly applied — is an event. We cannot accurately be said to perceive events;” (CP 1.336). He further states that “If I ask you what the actuality of an event consists in, you will tell me that it consists in its happening then and there. The specifications then and there involve all its relations to other existents. The actuality of the event seems to lie in its relations to the universe of existents.” (CP 1.24)

We often look for causes for events, but Peirce cautions us that, “Men’s minds are confused by a looseness of language and of thought which leads them to talk of the causes of single events. They ought to consider that it is not the single actuality, in its identity, which is the subject of a law, but an ingredient of it, an indeterminate predicate. Consequently, the question is, not whether each and every event is precisely caused, in one respect or another, but whether every predicate of that event is caused.” (EP p 396) Peirce notes that the chance flash or shock, say a natural phenomenon like a lightning strike or an accident, which by definition is not predictable, can itself through perception of or reaction to the shock “cause” an event. Chance occurrences are a central feature in Peirce’s doctrine of tychism.

Though events are said to occur, to happen or to take place, entities are said to exist. From Peirce again:

“The event is the existential junction of states (that is, of that which in existence corresponds to a statement about a given subject in representation) whose combination in one subject would violate the logical law of contradiction. The event, therefore, considered as a junction, is not a subject and does not inhere in a subject. What is it, then? Its mode of being is existential quasi-existence, or that approach to existence where contraries can be united in one subject. Time is that diversity of existence whereby that which is existentially a subject is enabled to receive contrary determinations in existence.” (CP 1.494).”

Nonetheless, “Individual objects and single events cover all reality . . . .” (CP 5.429). Other possibly useful statements by Peirce regarding events may be found under [4].

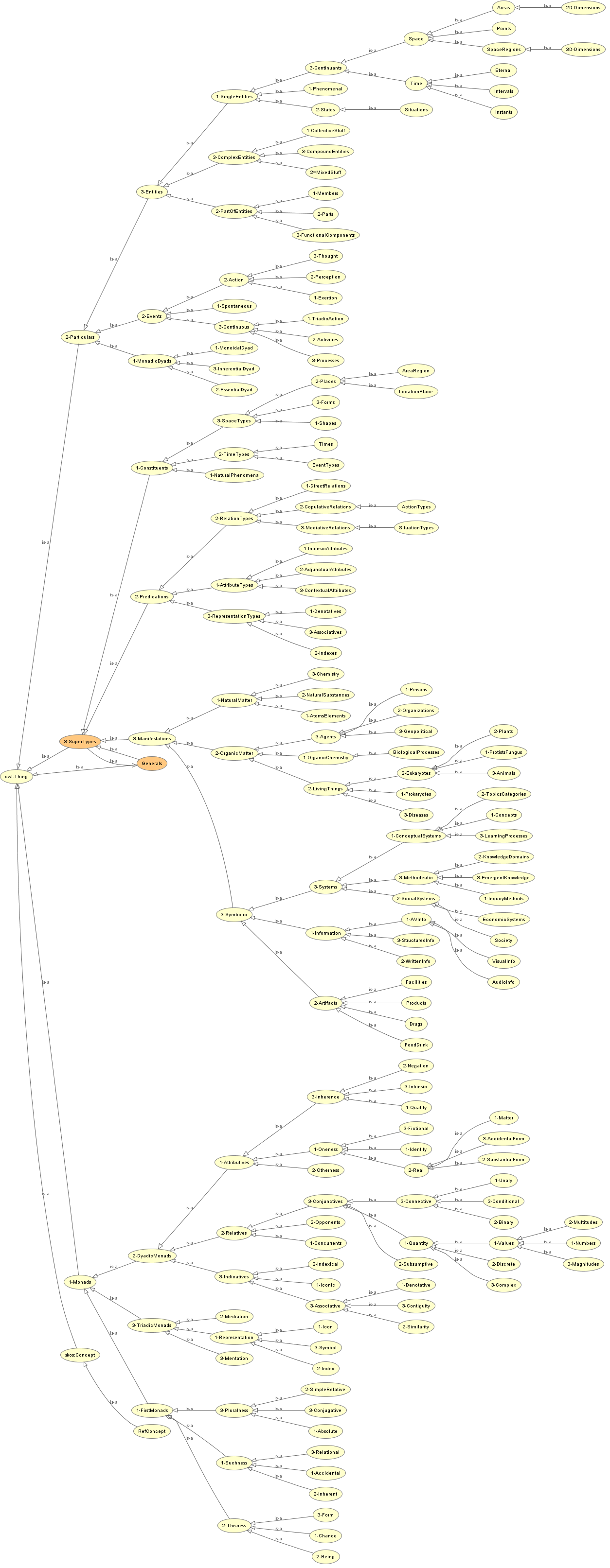

In these regards, we can see both entities and single events as individual instances within our KBpedia Knowledge Ontology, what we call Particulars, which represent the second (or Secondness) of the three main branches in KKO. Per our use of the universal categories to evaluate our subsequent category structures (see [1]) within Particulars, events are treated as a Secondness due to their triggering and “quasi-existence” nature, with entities treated as a Thirdness [5]. Like entities, we can also generalize events into types, which are placed under the third main branch of KKO, the Generals. Event types can be defined and are real in a similar way to entity types.

Within events, we can also categorize according to the three universal categories. What I present below are comments with respect to the event examples first mentioned in the introductory material above.

Events Resulting from Chance or Flash

As noted, the chance event, the unexpected flash or shock, is a Firstness within events. Peirce’s doctrine of tychism places a central emphasis on chance, being viewed as the source of processes in nature such as evolution and the “surprising fact” that causes us to re-investigate our assumptions leading to new knowledge.”Chance is any event not especially intended, either not calculated, or, with a given and limited stock of knowledge, incalculable.” (CP 6.602 ref). The surprising fact is the spark that causes us to continually reassess the nature of the world, to assess and categorize anew [6].

“Anything which startles us is an indication, in so far as it marks the junction between two portions of experience. Thus a tremendous thunderbolt indicates that something considerable happened, though we may not know precisely what the event was.” (EP What is a Sign, Sec 5) The chance event or shock joins energetic effort or perception as the stimulants of action. “Effort and surprise are the only experiences from which we can derive the concept of action.” (EP p 385)

The chance shock produces sensation, which itself may be a stimulant (reaction) to produce further action. “This is present in all sensation, meaning by sensation the initiation of a state of feeling; — for by feeling I mean nothing but sensation minus the attribution of it to any particular subject. In my use of words, when an ear-splitting, soul-bursting locomotive whistle starts, there is a sensation, which ceases when the screech has been going on for any considerable fraction of a minute; and at the instant it stops there is a second sensation. Between them there is a state of feeling.” (CP 1.332)

Still, the chance shock is the one form of event for which there is not a discernible cause-and-effect. It remains inexplicable because the triggering event remains unpredictable. “In order to explain what I mean, let us take one of the most familiar, although not one of the most scientifically accurate statements of the axiom viz.: that every event has a cause. I question whether this is exactly true . . . . may it be that chance, in the Aristotelian sense, mere absence of cause, has to be admitted as having some slight place in the universe . . . . ” (W4:546)

Events Resulting from Actions

We more commonly associate an event with action, and that is indeed a major cause of events. (Though, as we saw, chance events or accidents, as an indeterminate group, may trigger events.) An action is a Secondness, however, because it is always paired with a reaction. Reactions may then cause new actions, itself a new event. In this manner activities and processes can come into being, which while combinatorial and compound, can also be called events, including those of longer duration. That entire progression of multiple actions represents increasing order, and thus the transition to Thirdness.

One of Peirce’s more famous quotes deals with the question of action and reaction, even with respect to our cognition, and their necessary pairing:

“We are continually bumping up against hard fact. We expected one thing, or passively took it for granted, and had the image of it in our minds, but experience forces that idea into the background, and compels us to think quite differently. You get this kind of consciousness in some approach to purity when you put your shoulder against a door and try to force it open. You have a sense of resistance and at the same time a sense of effort. There can be no resistance without effort; there can be no effort without resistance. They are only two ways of describing the same experience. It is a double consciousness. We become aware of ourself in becoming aware of the not self. The waking state is a consciousness of reaction; and as the consciousness itself is two sided, so it has also two varieties; namely, action, where our modification of other things is more prominent than their reaction on us, and perception, where their effect on us is overwhelmingly greater than our effect on them.” (CP 1.324)

So, we see that actions can be triggered by chance, energetic effort, perceptions, and reactions to prior actions, sometimes cascading into processes involving a chain of actions, reactions and events.

Thoughts as Events

Peirce makes the interesting insight that thoughts are events, too. “Now the logical comprehension of a thought is usually said to consist of the thoughts contained in it; but thoughts are events, acts of the mind. Two thoughts are two events separated in time, and one cannot literally be contained in the other.” (CP 5.288) Similarly, in “Law of the Mind” Peirce calls an idea “an event in an individual consciousness” (CP 6.105) Through these assertions, the sticky question of thinking and cognition (always placed as a Thirdness by Peirce) is clearly put into the event category.

Events Resulting from Continuity

Of course, the essence of Thirdness is continuity, what Peirce called synechism. The very nature of continuity in a temporal sense are events, some infinitesimal, transitioning from one to another, with breaks, if we are to become aware of them, merely breaks in the continuity of time. Entities, at least as we define them, provide a similar function, but now over the continuity of space. All objects are deformations of continuous space. By this neat trick of relating events to time and entities to space, all of which is (yes, singular tense) continuous, Peirce nailed one of the hard metaphysical nuts to crack. Some claim that Peirce was the first philosopher to anticipate the space-time continuum [7].

In addition to its embeddedness and embedding into continuity, there are also actions which themselves are expressions of triadic relations. Peirce first says:

“Let me remind you of the distinction … between dynamical, or dyadic, action; and intelligent, or triadic action. An event, A, may, by brute force, produce an event, B; and then the event, B, may in its turn produce a third event, C. The fact that the event, C, is about to be produced by B has no influence at all upon the production of B by A. It is impossible that it should, since the action of B in producing C is a contingent future event at the time B is produced. Such is dyadic action, which is so called because each step of it concerns a pair of objects.” (CP 5.472)

In triadic action, the classic example is ‘A gives B to C’ (EP 2 170-171). The other classic triadic example is Peirce’s sign relation between object, sign and interpretant. Peirce adopted the term semiosis for this triadic relation and defined it to mean an “action, or influence, which is, or involves, a coöperation of three subjects, such as a sign, its object, and its interpretant, this tri-relative influence not being in any way resolvable into actions between pairs” (EP 2 411). Peirce’s reduction thesis also maintains that all higher order relationships (polyadic with more than three terms) can be decomposed to monadic, dyadic or triadic relations. All three are required to capture the universe or potential relations, but any relation can be reduced to one of those three [1]. Further, Peirce also maintained that the triadic relation is primary, with monadic and dyadic relations being degenerate forms of it.

Now, all symbols (therefore, also the basis for human language) are also a Thirdness. The symbol (sign) stands for an object which the interpretant understands to have a meaning relationship to the object. Symbols, too, may be causes of events. As Peirce states,”Thus a symbol may be the cause of real individual events and things. It is easy to see that nothing but a symbol can be such a cause, since a cause is by its definition the premiss of an argument; and a symbol alone can be an argument.” (EP, p 317).

It is not always easy to interpret Peirce. The ideas of creation and destruction, for example, would seem to be elements of Firstness, being closely allied to the idea of potentiality. Yet, as Peirce states, “But the event may, on the other hand, consist in the coming into existence of something that did not exist, or the reverse. There is still a contradiction here; but instead of consisting in the material, or purely monadic, repugnance of two qualities, it is an incompatibility between two forms of triadic relation . . . .” (CP 1.493) This statement seems to suggest that creation and destruction are somehow related to Thirdness. It is not always easy to evaluate where certain concepts fit within Peirce’s universal categories.

While I am unsure of some aspects of my Peircean analysis as to exact placements into Firstness, Secondness and Thirdness, what is also true is that Peirce sets conditions and mindsets for looking at these very questions. Ultimately open questions such as I mention are amenable to analysis and argumentation according to the principles underlying Peirce’s universal categories of Firstness, Secondness and Thirdness. The challenge is not due to the criteria for evaluation; rather, it comes from probing what is truly meant and implied within any question.

The Event-Action Model

What does not seem complicated or confusing is Peirce’s basic model for actions. Actions are grounded in events. As discussed above, Peirce provides for us broad and comprehensive examples of events — chance, actions, thoughts and continuity. Events are always things that occur to an individual (including the idea of an individual type). Peirce categorically states that “. . . the two chief parts of the event itself are the action and the reaction . . . .” (CP 5.424)

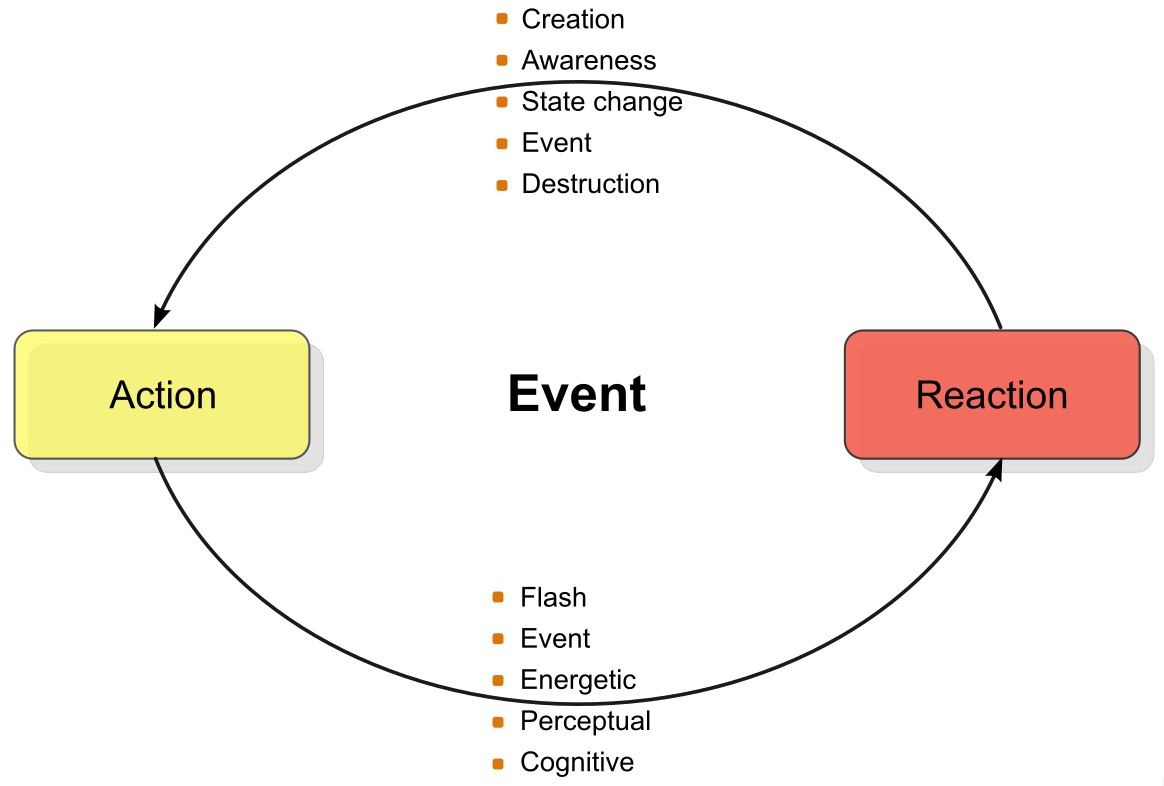

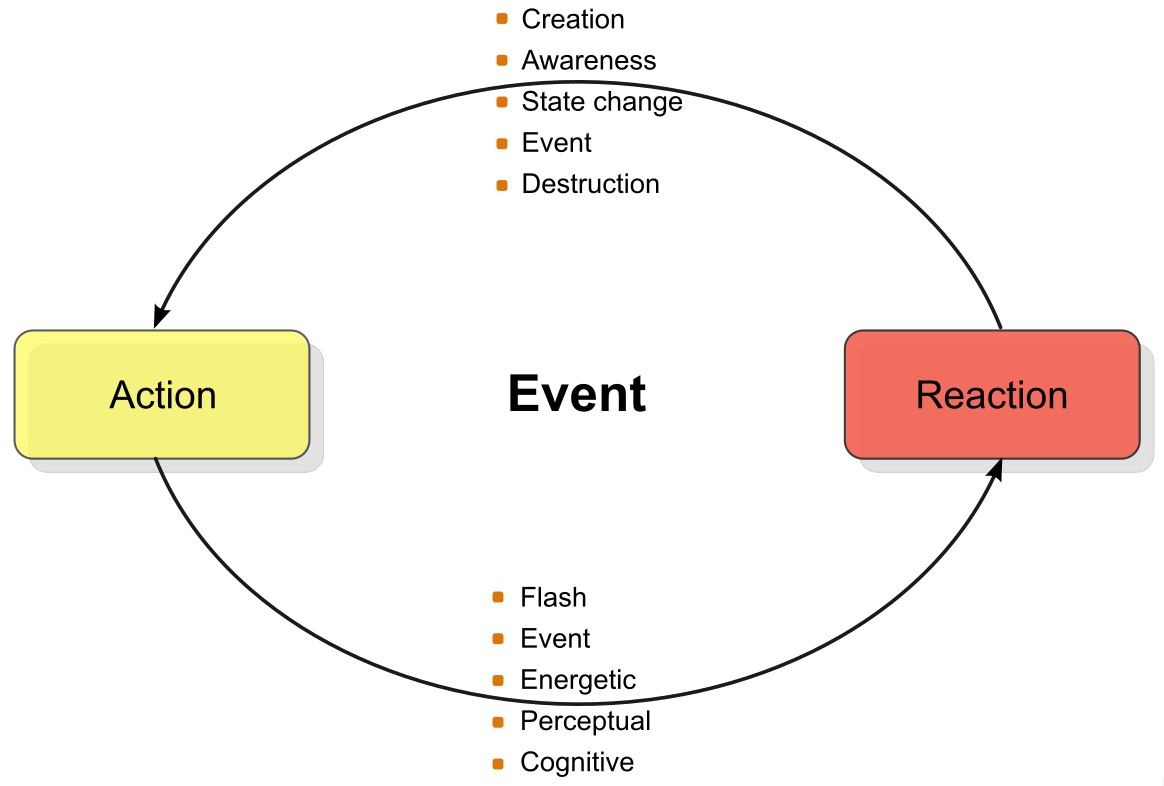

We now have the building blocks to enable us to diagram the event-action model embodied in KBpedia:

The KBpedia Event-Action Model

The single event may arise from any of the bulleted items shown on this diagram. Though every action is paired with a reaction, one or the other might be more primary for different kinds of events. As Peirce notes, the event represents a juxtaposition of states, the comparison of the subject prior and after the event providing the basis for the nature of the event. Each change in state represents a new event, which can trigger new actions and reactions leading to still further events. Simple events represent relatively single changes in state, such as turning off a light switch or a bolt of lightning. More complicated events are the topic of the next section.

Relating Events More Broadly to KBpedia

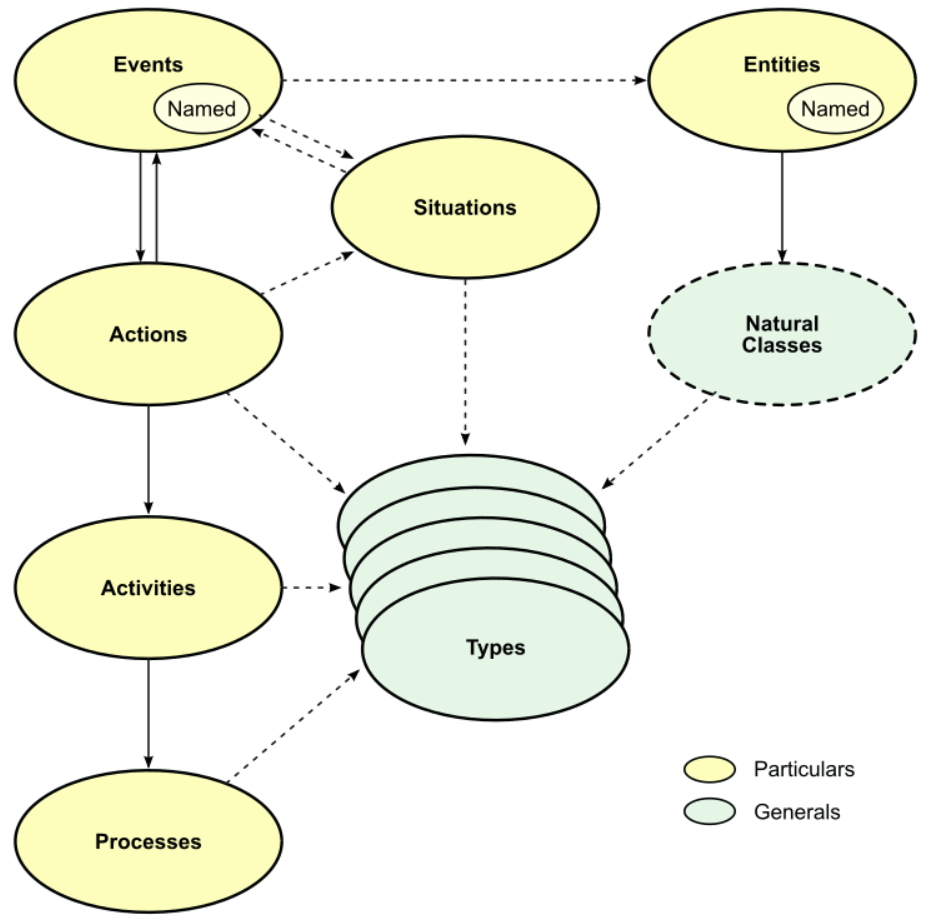

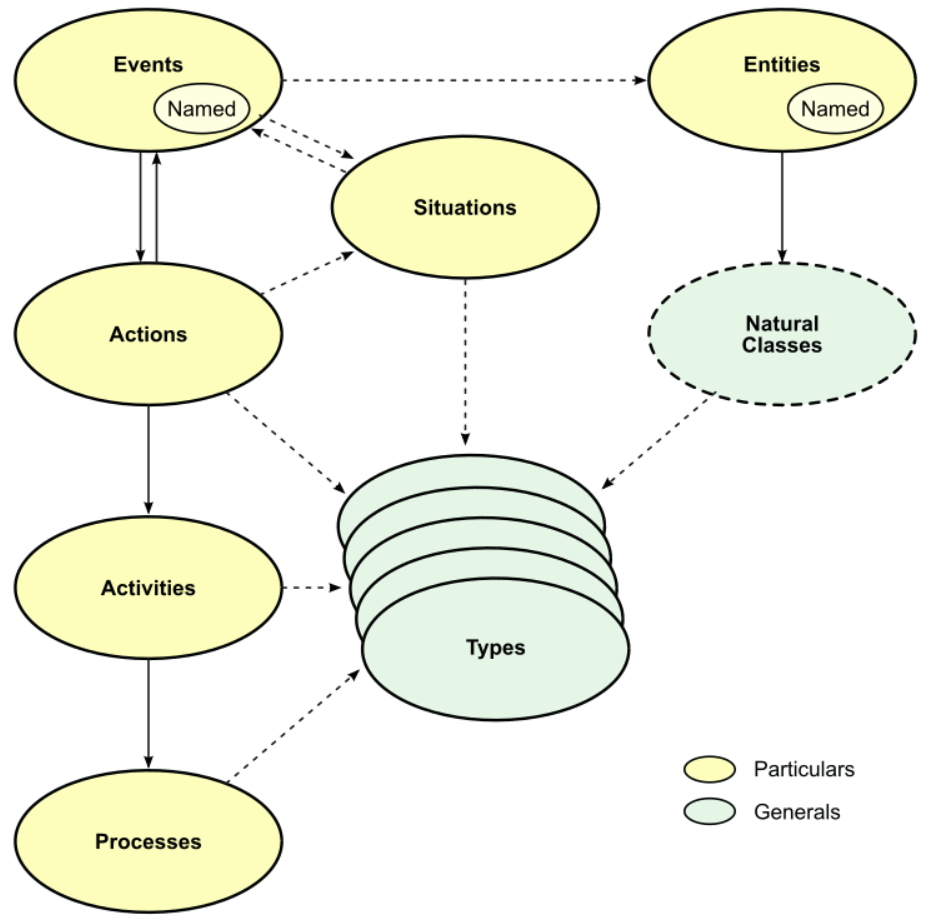

The next diagram relates events more broadly to KBpedia particulars and generals. Events may be the triggers for actions, both embedded within situations that provide their context (and often influence the exact nature and course of the event). Events also precede the creation or destruction of entities, which are manifestations, and events do occur over time to affect those very same entities. These events and these entities are singular, and if notable, we may give the individual instances of them names. These items are shown at the top of the diagram:

KBpedia Particulars and Types

On the left-hand portion of the diagram we have the cascade from events to actions to activities and then processes. The progression down the cascade requires the chaining together of events and actions and paired reactions, getting more ordered and purposeful as we move down the cascade. Of course, single events may trigger single actions and reactions, and events express themselves at every level of the cascade. Events and actions always occur in a situation, the context of which may have influence on the resulting nature of the event and its actions and reactions. This mediation is the exact reason that Thirdness is a logical foundation.

Parallel with events are entities, which themselves result from events. Entities, too, may be named. This side of the diagram cascade leads to classes or types of individual entities, which now become generals, and that may be classified or organized by types. A similar type aggregation may be applied to individual events, actions, activities and processes. At this point, we are moving into the territory of what is known as Peirce’s token-type distinction (particulars v generals). With generals, we now move beyond the focus of events; see further my own typology piece for this transition [8].

Events Provide the Entree to Understand Relations

Events are like the spark that leads us to better understand actions and what emerges from them, which in turn helps us better understand predicates and relations. These are topics for next parts in this series.

What we learn from Peirce is that events are quasi-entities, based on time rather than space, and, like entities, are a Secondness. Like entities, we can name events and intrinsically inspect their attributes. Events may also range from the simple to the triadic and durative. Events are the fundamental portions of activity and process cascades, and also capture such seemingly non-energetic actions like thought. Thought, itself, may be a source of further events and action, as may be the expressions of our thought, symbols. And actions always carry with them a reaction, which can itself be the impetus for the next action in the event cascade.

What this investigation shows us is that events are the real triggering and causative factors in reality. Entities are a result and manifestation of events, but less central to the notion of relations. Events, like entities, can be understood through Peirce’s universal categories of Firstness, Secondness and Thirdness.

Events help give us a key to understand the dynamic nature of Charles Peirce’s worldview. I hope in subsequent parts of this series to help elucidate further how an understanding of events helps to unmask the role and purpose of relations. Though entities, events and generals may all be suitable subjects for our assertions within knowledge bases and knowledge graphs, it is really through the relations of our system, in this case KBpedia, where we begin to understand the predicates and actions of our chosen domain.

This

series on KBpedia relations covers topics from background, to grammar, to design, and then to implications from explicitly representing

relations in accordance to the principals put forth through the

universal categories by

Charles Sanders Peirce. Relations are an essential complement to entities and concepts in order to extract the maximum information from knowledge bases. This series accompanies the next release of KBpedia (

v 150), which includes the relations enhancements discussed.

[2] Peirce citation schemes tend to use an abbreviation for source, followed by volume number using Arabic numerals followed by section number (such as CP 1.208) or page, depending on the source. For CP, see the

electronic edition of

The Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, reproducing

Vols. I-VI, Charles Hartshorne and Paul Weiss, eds., 1931-1935, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., and Arthur W. Burks, ed., 1958,

Vols. VII-VIII, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass. For EP, see Nathan Houser and Christian Kloesel, eds., 1992.

The Essential Peirce – Volume 1, Selected Philosophical Writings‚ (1867–1893), Indiana University Press, 428 pp. For EP2, see The Peirce Edition Project, 1998.

The Essential Peirce – Volume 2, Selected Philosophical Writings‚ (1893-1913), Indiana University Press, 624 pp.

[3] Roberto Casati and Achille Varzi, 2014. “

Events“,

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Aug 27, 2014. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

[4] What constitutes the

potentials, realized

particulars, and

generalizations that may be drawn from a query or investigation is contextual in nature. That is why the mindset of Peirce’s triadic logic is a powerful guide to how to think about and organize the things and ideas in our world. We can apply this triadic logic to any level of information granularity. Here are some further Peirce statements about events:

- “An event always involves a junction of contradictory inherences in the subjects existentially the same, whether there is a simple monadic quality inhering in a single subject, or whether they be inherences of contradictory monadic elements of dyads or polyads, in single sets of subjects. But there is a more important possible variation in the nature of events. In the kind of events so far considered, while it is not necessary that the subjects should be existentially of the nature of subjects — that is, that they should be substantial things — since it may be a mere wave, or an optical focus, or something else of like nature which is the subject of change, yet it is necessary that these subjects should be in some measure permanent, that is, should be capable of accidental determinations, and therefore should have dyadic existence. But the event may, on the other hand, consist in the coming into existence of something that did not exist, or the reverse. There is still a contradiction here; but instead of consisting in the material, or purely monadic, repugnance of two qualities, it is an incompatibility between two forms of triadic relation, as we shall better understand later. In general, however, we may say that for an event there is requisite: first, a contradiction; second, existential embodiments of these contradictory states; [third,] an immediate existential junction of these two contradictory existential embodiments or facts, so that the subjects are existentially identical; and fourth, in this existential junction a definite one of the two facts must be existentially first in the order of evolution and existentially second in the order of involution.”(CP 1.493)

- “A Sinsign (where the syllable sin is taken as meaning “being only once,” as in single, simple, Latin semel, etc.) is an actual existent thing or event which is a sign. It can only be so through its qualities; so that it involves a qualisign, or rather, several qualisigns. But these qualisigns are of a peculiar kind and only form a sign through being actually embodied.” (EP Nomenclature of Triadic; p 291) That is, a sinsign is either an existing thing or event; further, events have attributes.

- “Another Universe [Secondness] is that of, first, Objects whose Being consists in their Brute reactions, and of, second, the facts (reactions, events, qualities, etc.) concerning those Objects, all of which facts, in the last analysis, consist in their reactions. I call the Objects, Things, or more unambiguously, Existents, and the facts about them I call Facts. Every member of this Universe is either a Single Object subject, alike to the Principles of Contradiction and to that of Excluded Middle, or it is expressible by a proposition having such a singular subject.” (EP p 479) The latter is an event.

[5] Under Particulars, the instantiation of qualities (making them subjects as opposed to unformed potentiality) is the Firstness.

[7] See, for example, A. Nicolaidis, 2008. “

Categorical Foundation of Quantum Mechanics and String Theory,”

arXiv:0812.1946, 10 Dec 2008. It is not unusual to see grand claims for the foresight exhibited by Peirce in his writings, which sometimes have an inadequate basis for the claims of prescience. However, Peirce’s general observations often pre-date current, modern interpretations, even if not fully articulated.

Sometimes These Releases Get Complicated

Sometimes These Releases Get Complicated