Another Rung on the Ladder of Knowledge

Another Rung on the Ladder of Knowledge

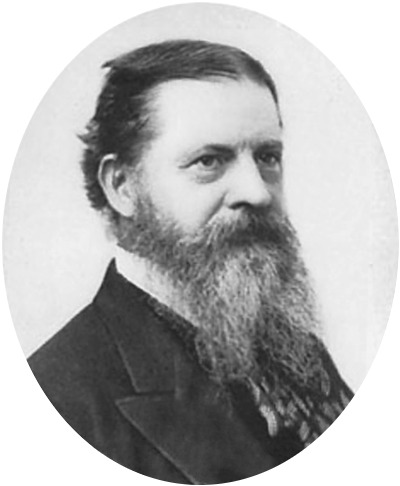

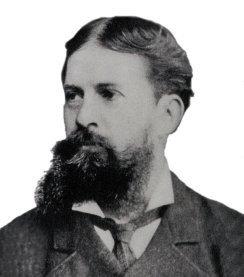

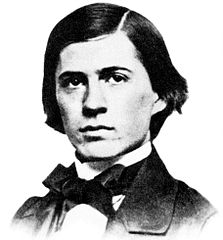

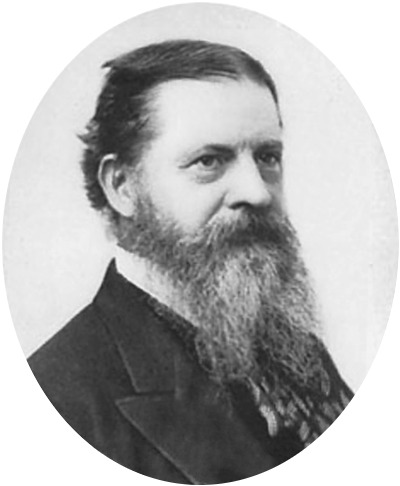

I suppose, like most philosophers, that Charles Sanders Peirce (1839-1914) often engenders much passion and strongly held views. Among the prominent authors who have written about Peirce are scholars, engineers, arm-chair philosophers, charlatans, physicists, confused thinkers, pendants, academics, linguists, mathematicians, cosmologists, biosemioticians, atheists, religionists, scientists, and writers, among other disciplines and viewpoints. Peirce maintained the discovery of truth is a community exercise, yet that consensus about many aspects of his writings eludes the Peircean community [1]. The strength of Peirce’s theories, I believe, resides most in the generals that may be derived from his world view. Despite the areas of disagreement, I think that a general conclusion shared in the Peircean community is that much can be learned about the nature of the world and knowledge of it by studying Peirce.

In this article, the last in my current series of why and how I study Peirce, I discuss the methods and approach — the methodeutic in Thirdness according to Peirce — that I use to interpret his writings. I want to continue to emphasize the general in Peirce’s writings, the Thirdness, that fixes my own beliefs [2]. These beliefs, while sufficient as a basis for action and learning (or habit), are not fixed in the sense of being inviolate. Quite the contrary. I am continuing to learn about Peirce, changing my views and beliefs as evidence presents itself. This evidence comes from either studying more of Peirce’s writings directly or learning from others’ scholarship and insightful interpretation.

Belief is not truth, and what we take today to be truth is fallible. Continuity, change, growth and learning are core concepts within Peirce’s conception of Thirdness. Peirce continued to question and test his own views, leading to changing statements and interpretation in many areas across his five decades of writings. Peirce would have never seen himself as infallible, and would disdain any of those who hold him as such. So we shall not [3].

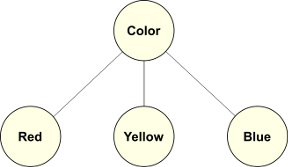

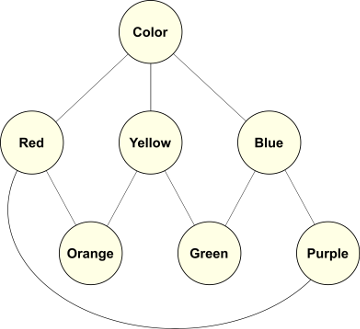

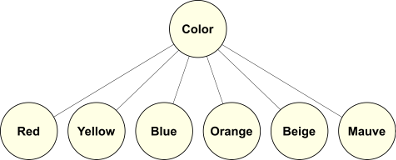

The very scheme of Peirce’s beliefs, what he rightfully termed his architectonic, is grounded in his universal categories of Firstness, Secondness, and Thirdness [4]. Each of these formative concepts is both necessary and sufficient for building all aspects of an understanding of reality, which in Secondness also gives us a basis for understanding the fictional as a contrast to that reality. All aspects of the knowable, experienced reality, what Peirce called the phaneron, can be reduced to one or more of these universal categories, in full or degenerate form [5].

Having died more than a century ago, Peirce was part of an age just on the cusp of electricity, wireless communications, the automobile, and the airplane. The discovery of relativity, atomic energy, quantum mechanics, and computers still resided mostly into the future. So how can Peirce speak to us about these modern things and knowledge? Well, at the most fundamental levels, Peirce is very much a big picture guy, seeking to understand the essences of existence and reality. By trying to grok Peirce’s mindset and methods, I believe we can address problems Peirce did not directly address himself. Because of his timeless insights, Peirce continues to provide adaptive guidance for our changing, modern world.

Why Important to Interpret Peirce

I have maintained throughout this series that Peirce is the greatest thinker ever in the realm of knowledge representation. Yet KR, as a term of art, was not a phrase used in Peirce’s time. True, Peirce wrote much on relations and representation (via his semiotic theory of signs) and provided many insights on the nature of information and knowledge, but he never used the specific phrase of “knowledge representation” [6]. Further, while he categorized the realm of science at least 20 different times (see below), and wrote on Charles Babbage and posited the use of electricity and logic gates for reasoning machines [7], he never attempted to categorize knowledge such as what we have undertaken with the KBpedia Knowledge Ontology (KKO). While I think Peirce had more than a glimmer of an idea that reasoning machines might someday be a reality, there was no need within his time to attempt to provide the specific representational framework for doing so.

Thus, the importance of studying Peirce for me has been to tease out those principles, design bases and mindsets that can apply Peircean thinking to the modern challenge of knowledge representation. This knowledge representation is like Peirce’s categorization of science or signs, but is broader still in needing to capture the nature of relations and attributes and how they become building blocks to predicates and assertions. In turn, these constructs need to be subjected to logical tests in order to provide a defensible basis for what is knowledge and truth given current information. Then, all of these representations need to be put forward in a manner (symbolic representation) that is machine readable and computable.

In reading and studying Peirce for more than a decade it has become clear that he had insights and guidance on every single aspect of this broader KR problem. The objective has been how to take these piece parts and recombine them into a coherent whole that is consistent with Peirce’s architectonic. How can Peirce’s thinking be decomposed into its most primitive assumptions in order to build up a new KR representation? As I argue in this article, the key to unlocking this challenge has been through an understanding of the universal categories and the mindset that resides behind them. In Peirce’s own term, the universal categories are the most “indecomposable” elements of his world view.

Of course, since Peirce himself never addressed the specific challenge of knowledge representation for computers, there is no guarantee that Peirce himself would endorse this current interpretation. Further, Peirce was a stickler for terminology and evolved and changed in his thinking over his long intellectual career. An appreciation of these factors is also important to do justice in posing a Peircean view of knowledge representation.

The Terminology Tarpits

Though Peirce frequently railed against nominalism, arguing instead for a realistic view of the world, he also was very attuned to names, labels and definitions. For example, he authored some 6,000 definitions of technical terms over the years for the Century Dictionary [8]. He was in constant search for the “correct” way to label his constructs. As one instance, at various times, Peirce called abductive reasoning hypothesis, abduction, presumption, and retroduction. He also called the methodeutic speculative rhetoric, general rhetoric, formal rhetoric, and objective logic. Such changing names were not uncommon with Peirce.

Because Peirce held that the understanding of a language symbol is a process of shared consensus among its community of users, he was generally loathe to use common terms for many of his constructs. Indeed, when one of his terms, pragmatism, was adopted by William James who gave it a different spin and interpretation, Peirce disavowed his earlier term and replaced it with the term pragmaticism. “So then, the writer [Peirce], finds his bantling ‘pragmatism’ so promoted, feels that it is the time to kiss his child good-by and relinquish it to its higher destiny; while to serve the precise purpose of expressing the original definition, he begs to announce the birth of the word ‘pragmaticism’, which is ugly enough to be safe from kidnappers” [9, pp 165-166].

This penchant for “ugly” terms is not uncommon with Peirce. As examples, here are some other terminology uses from Peirce’s writings:

| agapism |

coenoscopy |

interpretant |

phaneroscopy |

semeiotic |

| anancasticism |

cyclosy |

legisign |

pragmastic definition |

sinsign |

| apeiry |

dicent |

medisense |

pragmaticism |

speculative rhetoric |

| antethics |

entelechy |

methodeutic |

precission |

stecheotic |

| architectonic |

fallibilism |

objective idealism |

qualisign |

synechism |

| axiagastics |

hylozoism |

percipuum |

representamen |

transuasion |

| ceno-pythagorean |

hypostatic abstraction |

periphraxy |

retroduction |

tychasticism |

| chorisy |

idioscopy |

phaneron |

rheme |

tychism |

Examples of Obscure Peirce Terminology

Changing and “ugly” terminology is but the first of the difficulties in reading and understanding Peirce. His own evolution as a thinker, plus the interpretations of those who study them, also complicate matters. I cover this topic in the next section.

But a real point about interpretation, I think, is to try to get past his sometimes off-putting terminology. Mostly what is hard to understand are terms you may be encountering for the first time. There are rewards if you can see through the newness of this terminology to get to the meat underneath.

Eras and Changing Viewpoints

Peirce was often the first to acknowledge how he changed his views, with one set of quotes from early 1908 showing how his thinking about the nature of signs had changed over the prior two or three years [10]. Yet that was but a small snapshot of the changes Peirce made to his sign theories over time, or of his acknowledgments that his views on one matter or another had changed.

In his analysis of Peirce’s 70-plus definitions of the sign, Robert Marty distinguishes between the original three correlates of the triadic relation as ‘global triadic’ and the later six-element definition as being ‘analytic triadic’ [11, in reference to 5]. Besides this first elaboration, Peirce undertook a further extensive expansion of his theory of signs after the turn of the 20th century. In a new book [12], Jappy provides an intelligent analysis of this evolution of Peirce’s sign theories, focusing on his latter 28-sign scheme, what Jappy feels to be Peirce’s most mature (but still incomplete). Thus, with respect to signs alone, we can trace an evolution or maturation of Peirce’s sign theories that went from 3 → 6 → 10 → 28 → 66 elaborations. The latter 28 and 66 schemes remained incompletely developed at the time of Peirce’s death.

Similarly, Peirce’s classification of the sciences also went through considerable changes. Beverly Kent conducted a thorough analysis in 1987, much based on unpublished manuscripts at the time, that documents at least 20 different classifications of the sciences from Peirce over the period of 1866 to 1903 (the last “perennial”), with minor ones in between [13]. In addition to signs and the classification of the sciences, examples abound of evolving terminology or thinking by Peirce for other topics for which he is commonly known, such as logic (deductive v inductive v abductive), pragmatism, continuity, infinitesimals, and mathematics.

Of course, it is not surprising that an active writing career, often encompassing many drafts, conducted over a half of a century, would see changes and evolution in thinking. Many scholars have looked to specific papers or events in order to understand this evolution in thinking. Max Fisch divided Peirce’s philosophy development into three periods: 1) the Cambridge period (1851-1870); 2) the cosmopolitan period (1870-1887); and 3) the Arisbe period (1887-1914) [14]. Murphey split Peirce’s development into four phases: 1) the Kantian phase (1857-1866); 2) three syllogistic figures (1867-1870); 3) the logic of relations (1879-1884); and 4) quantification and set theory (1884-1914) [15]. Brent has a different split more akin to Peirce’s external and economic fortunes [16]. Parker tends to split his analysis of Peirce into early and mature phases [17]. It is a common theme within major scholars of Peirce to note these various changes and evolutions.

Some of this analysis asserts breakpoints and real transitions in Peirce’s thinking. Others tend to see a more gradual evolution or maturation of thinking. Some of the arguments are clearly aimed at bolstering whatever particular thesis the author is putting forward. Such is the nature of scholarship, and to be expected.

For me, I take a pragmatic view of these changes. First, some of Peirce’s earliest writings, particular his 1867 “On a New List of Categories’ [18], but also mid-career ones, are amazingly insightful and thought-provoking. There is tremendous value in these earlier writings, often infused with genius. Peirce, after all, was in the prime of his powers. Sure, I can see where some points have evolved or prior assertions have changed, but Peirce is also good at flagging those areas he sees as having been important and earlier in error. I therefore tend to rely most on his later writings, when a hard life lived, maturity and experience added wisdom and perspective to his thoughts. I tend to see his later changes more as nuanced or mature, rather than fundamental breaks with prior writings. I see tremendous continuity and consistency of world view in Peirce over time.

Sure, at the level of how specific items or ideas change over time it is important to be cognizant of when a Peirce quote or writing occurred. The jumbled nature of the original Collected Papers means they need to be used with caution, since they have no chronology. Most contemporary Peirce scholars now tend to date by year the passages they quote in order to overcome this problem. I think this is good practice, and for which I am increasingly trying to adhere. Also, I tend to not like his later terminology, since I think it errs on the side of obscurity in order to be precise, which limits its understandability to a broader community. Peirce should have realized that understandability holds sway over individualized perspective. He was silly to argue with James about the term pragmatism, as James was doing so much to promote awareness of Peirce’s ideas.

The Lens of the Universal Categories

Chronologies, terminologies, or evolutions aside, still the question remains: How can one apply Peirce and his ideas to today’s challenges? What is the essence of trying to approach and solve problems by Peircean means? Is there a mindset by which we can think through contemporary problems in domains unheard of in Peirce’s time? Are there indeed timeless truths?

I think there are.

To me, slicing through all of the complexity and the noise, are Peirce’s universal categories of Firstness, Secondness and Thirdness. I find it amazing and consistent how much Peirce himself relies on the universal categories in his own thinking and analysis. There must be something at the heart of these universal categories that make them such a powerful lodestone.

The first hurdle, I think, in attempting to understand the universal categories is the absolute abstractness of the terms Firstness, Secondness and Thirdness. In this case, I believe Peirce’s terminology fussiness to be exactly what is proper. Since, ultimately, all reality, all potential, and all emergence derives from these elements, nothing other than one, two and three will do. Everything that is, may be, or could surprise us arises from these elements. This is the absolute ground. Nothing further can be decomposed from these elements, yet everything that is and is conceivable is built from these categories. I don’t mean to be or sound religious; just logical.

So, if we have such fundamental building blocks at hand, how can we begin to understand their nature, use and implications? How can we incorporate the universal categories into our own methodeutic? How can our thinking, the ultimate Thirdness, leverage these elements?

As might be expected, Peirce tried to get at this very question through the idea of continuity, the force at the heart of Thirdness. The universal categories are not static, but dynamic. The occasional “surprising fact” alters what we think we know about reality, which causes us to re-inspect and re-categorize our world. The dynamic universal categories, faced with the unexpected chance arising in Firstness, ripple through our awareness (reality) to cause a new understanding of the state of existence (Secondness). The universal categories give us the primitive elements by which we can again categorize and generalize our new world, a factor of Thirdness. And so the cycle continues. Truth, understood to be a limit function, gets constantly exposed as all of us test and affirm these new realities.

Peirce, the logical categorizer, concerned with methods, and interested in pragmatic approaches and solutions, understood that how we categorize our constantly emerging worlds was fundamental. His pragmatic maxim helps us decide among many possible alternatives. Perhaps we can follow his natural classification guidelines, an item of keen interest to him, and one which I have previously discussed [19], as a way to better appreciate what these universal categories of Firstness, Secondness and Thirdness are and mean, as we work to categorize our emerging world anew.

One way to do that is to follow Peirce’s directive for determining a natural class by “an enumeration of tests by which the class may be recognized in any one of its members” [20]. So, as to better understand the ideas of Firstness, Secondness and Thirdness, I have assembled as many examples as I could find from Peirce’s writings of these members of the universal categories. The following table lists these 70 or so examples of Firstness, Secondness and Thirdness, the contexts in which they arose, and a citation where to find the supporting material in Peirce’s writings:

|

Firstness |

Secondness |

Thirdness |

|

| Moods or Tones |

first |

second |

third |

[21] |

| Conceptions of First, Second, Third |

independent |

relative |

mediating |

[22] |

| The Categories |

monads |

particulars |

generals |

[23] |

| Time |

“present” |

“past” |

“future” |

[24] |

| Cognition / Space |

point |

line |

triangle / sphere |

[25] |

| Movement |

position |

velocity |

acceleration |

[26] |

| Modes of Being |

possibility |

existence |

law |

[27] |

| Seconds |

internal |

external |

Thirdness |

[28] |

| Thirds |

mixtures |

comparisons |

intelligibles |

[29] |

| Modality |

possibility |

actuality |

necessity |

[30] |

| Phenomena 1 |

sensations |

reactions |

generals |

[31] |

| Phenomena 2 |

qualities of phenomena |

actual facts |

laws (and thoughts) |

[32] |

| Active Elements |

chance |

law |

habit-taking |

[33] |

| Existence |

chaos |

regularity |

continuity |

[34] |

| Continuity |

feeling |

effort |

habit |

[35] |

| Mathematics |

quality |

facts |

laws |

[36] |

| Ceno-Pythagorean Categories |

originality |

obsistence |

transuasion |

[37] |

| Form |

tone |

token |

type |

[38] |

| Being |

quality |

relation |

representation |

[39] |

| Protoplasm |

sensibility |

motion |

growth |

[40] |

| Natural Selection |

individual variation |

heritability |

elimination of unfavored characters |

[41] |

| Modes of Evolution |

absolute chance |

mechanical necessity |

law of love |

[42] |

| Doctrines of Evolution |

tychasticism |

anancasticism |

agapasticism |

[43] |

| Consciousness 1 |

feeling |

sense of action/reaction |

sense of learning |

[44] |

| Consciousness 2 |

feeling |

altersense |

medisense |

[45] |

| Consciousness 3 |

immediate feeling |

polar sense |

synthetical consciousnes |

[46] |

| Thought 1 |

abstraction |

suggestion |

association |

[47] |

| Thought 2 |

possibility |

information |

cognition |

[48] |

| Thought 3 |

thought-sign |

connected |

interpreted |

[49] |

| Synthetical Consciousness |

association by contiguity |

association by resemblance |

intelligibility |

[50] |

| Mind |

feelings |

reaction-sensations |

conceptions |

[51] |

| Logical Mind |

ideas |

ideas from prior ideas |

ideas from prior processes |

[52] |

| Experiences |

simples |

recurrences |

comprehensions |

[53] |

| Information |

intensions |

extensions |

comprehensions |

[54] |

| Knowledge Representation |

attributes |

individuals |

types |

[55] |

| Characters or Predicates |

internal |

external |

conceptual |

[56] |

| Relations |

attributes |

external relations |

representations |

[57] |

| Representation |

sign |

object |

interpretant |

[58] |

| Sign-Object |

icon |

index |

symbol |

[59] |

| Nature of Signs |

qualisign |

sinsign |

legisign |

[60] |

| Kinds of Characters |

singular characters |

dual characters |

plural characters |

[61] |

| Symbols |

words (or terms) |

propositions |

arguments |

[62] |

| Sign-Interpretant 1 |

emotional interpretant |

energetic interpretant |

logical interpretant |

[63] |

| Sign-Interpretant 2 |

rhemes |

dicisigns |

arguments |

[64] |

| Signs 1 |

possibles |

things |

collections |

[65] |

| Signs 2 |

abstractives |

concretetives |

collectives |

[66] |

| Propositions |

hypothetical |

categorical |

relative |

[67] |

| Logical Terms |

monads |

dyads |

triads |

[68] |

| Assertions |

possible modality |

actual modality |

necessary modality |

[69] |

| Reasoning |

what is possible |

what is actual |

what is necessary |

[70] |

| Logical Thinking |

clearness of conceptions |

clearness of distinctions |

clearness of practical implications |

[71] |

| Logic Methods |

abductions |

deductions |

inductions |

[72] |

| Logic |

speculative grammar |

logic and classified arguments |

methods of truth-seeking |

[73] |

| Sciences of Discovery |

mathematics |

philosophy |

special sciences |

[74] |

| Philosophy |

phenomenology |

normative science |

metaphysics |

[75] |

| Normative Science |

logic |

ethics |

aesthetics |

[76] |

| Concepts of Metaphysics |

spontaneity |

dependence |

mediation |

[77] |

| Others |

complete in itself, freedom, free, measureless variety, freshness, multiplicity, manifold of sense, peculiar, idiosyncratic, suchness, one, new, spontaneous, vivid, sui generis |

otherness, comparison, action, dichotomies, mutual action, will, volition, involuntary attention, shock, sense of change, here and now, compulsion, state, occurrence, negation |

idea of composition, continuity, moderation, comparative, reason, sympathy, intelligence, structure, regularities, conduct, representation, middle, learning, conditional |

[78] |

C.S. Peirce’s Universal Categories in Relation to Various Topics

Though atheists and religionists alike argue Peirce’s belief or not in God, I also find this statement by him to be another powerful expression of the universal categories: “The starting-point of the universe, God the Creator, is the Absolute First; the terminus of the universe, God completely revealed, is the Absolute Second; every state of the universe at a measurable point of time is the third.” (CP 1.362)

It took me a while to realize that Firstness, Secondness, and Thirdness are not a linear sequence, nor one in time. In fact, Peirce likens Firstness to the present, Secondness to the past, and Thirdness to the future [24]. All possibilities, Firstness, reside in the absolute present, “for nothing is more occult” (CP 2.85), the instance at which they act or are acted upon or perceive such changes causes them to come into existence, or Secondness, in relation or contrast with other instances and events, because what is real is past. The continuity of these instances through space and time, the future, enables new contexts and generalities arising from what we can learn from Secondness and Firstness. Chance events in Firstness may spring “surprises” in Secondness that trigger new cognition or mediation in Thirdness, which potentially predicates a new basis for categorization, certainly in the sense of knowledge representation, my chosen frame of reference.

My thesis is that studying these assignments in relation to the various contexts is one way to internalize the mindset of the universal categories. At the most fundamental level we can see Firstness as the raw, unexpressed possibilities of the current problem set, the building blocks for the new category, if you will. Chance is the root aspect of Firstness, which means any of these possibilities may express themselves in surprising ways, perhaps causing the need for new categorization. The actual things or events of the new category, as made manifest by their interaction or contact with what also exists in the domain at hand, provide the actual instances of Secondness. And, the generalities or continuities among these instances, classed as best we can in a natural manner, provide the Thirdness of this domain. The best way to glean meaning from this table is through deep study and contemplation.

In the context of knowledge representation, we begin with these foundational aspects of the universal categories and then keep analyzing and categorizing following this mindset. I think it is evident in the table above, sometimes to multiple levels depending on context (which requires studying some of the supporting material to the table), that Peirce applied this same method. Where questions arise about which universal category to assign something, we look to Peirce and later scholars to see if prior determinations have been postulated and argued. If so, we test those assumptions and adopt or not those assignments, based on our own logical assessments. We continue this process as we get deeper and more specific in our categorizations. No matter what the assignment, each should be subject to questioning and testing by the community of users, perhaps altering those assignments as better information or better logic is applied to the assignments. This is the process that has been followed in developing the KBpedia Knowledge Ontology (KKO), the knowledge graph of some 200 concepts that provides the upper-level scaffolding for our knowledge representation efforts.

As of the date of this writing, there is NO other knowledge representation framework besides KKO that explicitly embraces Peirce’s universal categories of Firstness, Secondness and Thirdness. While many, many insights from Peirce’s writings contribute to how we approach representing knowledge in our systems, the adoption of the mindset of universal categories is by far the most important element in how we go about constructing our representations.

A Synthetic Mindset Through Peirce’s Architectonic

Unfamiliar terminology and a triadic foundation to his philosophy make Charles Peirce a difficult guide to initially follow. Further, there are many dimensions, each richly layered, to his guidance. For those who have stayed the course, Peirce has become an invaluable guide.

The overarching framework of Peirce’s philosophy — his architectonic — is grounded in his universal categories of Firstness, Secondness and Thirdness. As a scientist and logician, Peirce applied this mindset in pragmatic and testable ways. These methods, indeed the scientific method itself, further guide how and where to apply this mindset in ways that are economical and promise the most knowledge among all of the possible paths of inquiry. Peirce’s fierce realism, the belief there is reality beyond our own minds, and his insistence that this reality is subject to inquiry and the fixation of belief leading ever closer to truth, is distinctly different than the mind-body duality put forward by Descartes.

Richard Bernstein in a recent book [79], calls this viewpoint a sea change:

“Pragmatism begins with a radical critique of Cartesianism. In one fell swoop, Peirce seeks to demolish the inter-related motifs that constitute Cartesianism [mind-body duality; primacy of personal experience; doubt as a starting condition; there are incontrovertible truths to be discovered] . . . . We can view the development of pragmatism from Peirce until its recent resurgence as developing and refining this fundamental change of philosophical orientation — this sea change. A unifying theme in all the classical pragmatists as well as their successors is the development of a philosophical orientation that replaced Cartesianism (in all its varieties).” (pp 18-19)

Our real world is constantly changing, constantly unfolding. Our real world is viewed by all of us differently, based on background, predilection, perspective and context. What we think we know about the world today is subject to inquiry and new insights. New factors are constantly arising to shift what we think we know about ourselves and our place in the world.

Knowledge representation by computers that does not explicitly account for perspective, meaning, and interpretation is doomed to be wooden and unable to handle context. Such is the state of art today. We do not all need to agree on the specifics or any single interpretation of what our domains of inquiry may be. But we do need a framework that can respect and model those differences.

To sum up, how I interpret Peirce embraces three perspectives. First, given the breadth of Peirce’s insights, I try to read as much by him and about his writings by others as I can. This exposure helps set a rich milieu for my own insights, but also in interpretation and critical judgment. Second, despite my awe of Peirce’s genius, I do not treat his writings as gospel. Were he alive today, I have no doubt that the massive increase in knowledge and information since his day would cause him to alter his own viewpoints — perhaps substantially so in some areas. There is no similar reason why any of us should shy from questioning any of Peirce’s assertions. Yet, given Peirce’s immense powers of logic, one better be well prepared with evidence and sound reasoning before undertaking such a challenge.

And, third, and most fundamentally, I try to view how to represent knowledge through the lens of Peirce’s universal categories. The tasks of defining and organizing knowledge demand that we bring meaning, context and perspective to the task. Peirce stood on the shoulders of the giants before him. We can now stand on Peirce’s shoulders to mount the next rung on the ladder of knowledge. I believe Peirce’s universal categories and what they imply offer the next adaptive climb upward for knowledge representation. As Bernstein states, “Peirce opened up a new way of thinking that is still being pursued today in novel and exciting ways by all those who have taken the pragmatic turn. This is the sea change he helped initiate.” (p 52)

[1] Many of the Peirce quotations are drawn from

The Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, reproducing

Vols. I-VI, Charles Hartshorne and Paul Weiss, eds., 1931-1935, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., and Arthur W. Burks, ed., 1958,

Vols. VII-VIII, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass. The citation scheme used for these sources is commonly seen in Peirce scholarship, and is volume number using Arabic numerals followed by section number from the collected papers, shown as, for example, CP 1.208.

[2] Peirce discusses this topic in his seminal paper, Charles S. Peirce, 1877. “The Fixation of Belief,”

Popular Science Monthly 12:1-15, November 1877

[3] “To be blinded by the peculiar strength of his thinking into a type of reverence that has always been common, would certainly be to violate the very spirit which animated him.” p. xv; from the editor’s introduction to Justus Buchler, ed., 1940.

Philosophical Writings of Peirce, Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd., reissued by Dover Publications, New York NY, 1955.

[5] Peirce’s original three universal categories were expanded to six by adding what he called one “degenerate” form to Secondness and two “degenerate” forms to Thirdness, increasing the original three by an additional three. See further CP 1.365-367.

[6] The exact origin of the phrase “knowledge representation” is unclear. Given its role in symbolic representations to computers, a branch of artificial intelligence, the phrase would not be expected to be used in that sense until the mid-20th century. Knowledge representation first became prominent through systems like the GPS problem-solving program (A. Newell, J.C. Shaw, and Herbert A. Simon, 1959. “Report on a General Problem-solving Program,” in

Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Processing, pp. 256–264, KRL (the Knowledge Representation Language, see Daniel G. Bobrow and Terry Winograd, 1976. “An Overview of KRL, A Knowledge Representation Language,”

Stanford Artificial Intelligence Laboratory Memo AIM 293, 1976), and then the KR thesis work of Ron Brachman at Harvard (1978) followed by his early technical papers and books; see especially the popular Hector J. Levesque and Ronald J. Brachman, 2004.

Knowledge Representation and Reasoning. Amsterdam: Elsevier/Morgan Kaufmann. ISBN 1-55860-932-6.

[7] References to Charles Babbage may be found at CP 2.56 and CP 4.611. For electrical logical machines, see Charles S. Peirce, 1993, “Letter, Peirce to A. Marquand” dated 30 December 1886, in Kloesel, C. et al., eds.,

Writings of Charles S. Peirce: A Chronological Edition: Volume 5: 1884–1886. Indiana University Press: 421-422, with an image of the letter page with the circuits on p. 423.

[8] Charles S. Peirce, 1982.

Writings of Charles S. Peirce: A Chronological Edition – Volume 1, 1857-1866, compiled by the editors of the Peirce Edition Project, Indiana University Press, August 1982, 736 pages,ISBN: 978-0-253-37201-7. The editors note Peirce contributed to 16,000 entries, most in mathematics and logic, with 6,000 written solely by Peirce

[9] Charles S. Peirce, “What Pragmatism Is,”

The Monist, Vol. 15, No. 2 (April, 1905), pp. 161-181; see

http://www.jstor.org/stable/27899577; also CP 5.414. He also expands on this general theme in Charles S. Peirce, 1906. “Prolegomena to an Apology for Pragmaticism,”

The Monist, Vol. 16, No. 4 (October, 1906), pp. 492-546; see

http://www.jstor.org/stable/27899680[10] Charles S. Peirce, 1908. “The Ten Main Trichotomies of Signs,” in “Excerpts to Lady Welby”, in Charles S. Peirce, 1998.

The Essential Peirce – Volume 2: Selected Philosophical Writings (1893-1913), edited by the Peirce Edition Project, Indiana University Press, June 1998, 624 pp., ISBN: 978-0-253-21190-3; also CP 8.363-365.

[11] See his very useful ‘Analysis of the 76 definitions of the sign’ http://www.iupui.edu/~arisbe/rsources/76DEFS/76defs.HTM (Accessed March 2016).

[13] Beverly Kent, 1987.

Charles S. Peirce: Logic and the Classification of the Sciences, McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal, 258 pp.

[14] Max H. Fisch, “Peirce’s Arisbe: The Greek Influence in his Later Philosophy,” in

Peirce, Semiotic, and Pragmatism, p. 227

[15] Murray G. Murphey, 1993.

The Development of Perice’s Philosophy. Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., Indianapolis.

[16] Joseph Brent, 1998.

Charles Sanders Peirce: A Life (2nd edition), Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

[17] Kelly A. Parker, 1998.

The Continuity of Peirce’s Thought. Vanderbilt University Press, Nashville.

[18] Charles S. Peirce, 1867. “On a New List of Categories,”

Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 7 (1868), 287–298. Presented, 14 May 1867. See CP 1.545-559.

[20] Peirce sets this forth as one of his conditions for determining a natural classification; see CP 1.224.

[21] CP 1.355; also, Cosmogenic Philosophy, EP 1.297

[23] This exact categorization was never used directly by Peirce (or so my investigations to date suggest). However, it is clear throughout his writings that he relates monads to Firstness, ‘particulars’ and ‘particularities’ to Secondness, and ‘generals or ‘generalities’ to Thirdness. Further, these terms are understood and used in other categorization schemes, such as those by Aristotle and Kant. We also see, by this chart, that Peirce himself employs many different terms for his universal categories. We have chosen these to be the three main categories in the

KBpedia Knowledge Ontology for these reasons. See further CP 1.300-338.

[24] CP 2.84-86; see also 2.146; it is NOT 1 –> 2 –> 3 present v

hic et nunc ; CP 5.459-463

[29] CP 1.366; This is an example of what Peirce called ‘degenerate’ categories of the category. Degenerate means that it is a component of the category, but not sufficient as a concept in the 1

o and 2

o[34] CP 1.411 and CP 1.175

[35] CP 6.201-202; also called Tritism or Synechism (or “all that there is”)

[37] CP 2.87-89; Peirce using his obscure labels in seeking exactitude

[39] CP 1.555 and CP 2.418; the initial categories were actually bracketed by Being and Substance (5 categories total). In CP 4.3 Peirce re-named these labels as

quality,

reaction and

mediation. However, in that same passage he says, “How the conceptions are named makes, however, little difference.” I have chosen to retain his earlier names because they are more commonly referenced and it retains the idea of ‘representation’, more allied with the idea of

knowledge representation.

[45] CP 7.551; thought is taken to be as equivalent to medisense

[47] The analysis of the labels and relations is provided in these two articles: M.K. Bergman, 2017. “

KBpedia Relations, Part III: A Three-Relations Model,”

AI3:::Adaptive Information blog, May 24, 2017; and M.K. Bergman, 2017. “

KBpedia Relations, Part IV: The Detailed Relations Hierarchy,”

AI3:::Adaptive Information blog, June 27, 2017.

[54] Peirce did not explicitly list these terms, but they can be readily and logically derived from CP 2.419-421. The idea of information being a product of depth (1

o, intensionality) times breadth (2

o, extensionality) is quite insightful

[55] Though ‘general type’ is a common term for Thirdness in Peirce’s writings, he rarely used ‘attibute’ and preferred particulars to ‘individuals’. ‘Attributes’ and ‘individuals’ are now in modern usage, and clearly refer to 1o and 2o, respectively.We have chosen these two terms for use in the

KBpedia Knowledge Ontology for these reasons.

[56] Somewhat modified from CP 5.469 cf, with external and conceptual replacements supported by the senses of the accompany text

[57] Taken from the analysis of Peirce documented in [47]; these are the terms chosen for use in terms for use in the

KBpedia Knowledge Ontology[58] CP 1.339; ‘representation’ is also called a ‘sign’

[59] CP 1.191; can also be called ‘speculative grammar’ or ‘nature of signs’; in Jappy 2017 this is called ‘Sign-Object’, Table 1.2 A Synthesis of MSS R478 and R540, 1903

[60] CP 4.537 fn 3; called simply ‘Sign’ in Jappy 2017, Table 1.2 A Synthesis of MSS R478 and R540, 1903.

[61] CP 1.370-371; can substitute ‘facts’ for ‘characters’

[62] CP 2.95, also CP 8.337; CSP also expresses ‘arguments’ as inferences or syllogisms

[64] From Jappy 2017, Table 1.2 A Synthesis of MSS R478 and R540, 1903

[65] CP 8.366, with respect to the nature of dynamical objects

[66] CP 8.366, with respect to the nature of dynamical objects

[72] CP 2.98; in an earlier version, I listed ‘abduction’ as a Thirdness, but I was corrected on the Peirce-L mailing list. On the other hand, abduction is at the interface between Thirdness and Firstness, since it is the source of the possibilities that need to be considered for a given category. The dynamic nature of Peirce’s semiosis is part of the sign-making and -recognition process.

[74] CP 1.239-242; the ‘special sciences’ include the physical (physics, chemistry, biology, astronomy, geognosy, and whatever may be like these sciences) and the psychical (psychology, linguistics, ethnology, sociology, history, etc.) sciences

[77] CP 3.422; also, Forms of Rhemata (singular, dual or plural)

[78] Mostly random notes teken from various Peirce writings.

[79] Richard J Bernstein, 2010.

The Pragmatic Turn, Polity Press, Malden, MA. 2010.

Some Basic Use Cases from KBpedia

Some Basic Use Cases from KBpedia