Language is Essential to Communication

Language is Essential to Communication

I recently began a series on the structured Web and its role in the continued evolution of the Internet. This next installment in the series probes in greater depth the question of What is structure? in reference to data and Web expressions, with an emphasis on terminology and definitions.

This post ties in with a new best-practices guide published by Chris Bizer, Richard Cyganiak, and Tom Heath — called the Linked Data Publishing Tutorial — that provides definitions and viewpoints from the perspective of the use of RDF (Resource Description Framework) and W3C practices. My initial post in this series and their tutorial occasioned Kingsley Idehen to post his own Linked Data and the Web Information BUS entry, adding the valuable perspective of practices and terminology going back to the early 1990s in object and relational database systems and standards such as ODBC.

All of these efforts share a desire to craft practices, language and terminology to help promote the availability and interoperability of useful data on the Web.

A challenge for the semantic Web community is to craft language that is clear and understandable to the lay public and Web developers, something which it has often done poorly.Some problematic terms include information resource, non-information resource, dereferencing, bnode, content negotiation, representation, URL re-writing, and others.

This piece only tackles ‘non-information resource‘ head on. Discussion of other problematic terms awaits another day.

These posts caused Kingsley and me to engage in a prolonged discussion about definitions and terms. I acted as the unofficial scribe, which I attempt to more generally capture and argue below. If you like the ideas below, you may credit both of us; if you don’t, ascribe any errors or omissions to me alone [1].

The Basic Framework and Argument

The basic observation related to the structured Web is that it is a transition phase from the initial document-centric Web to the eventual semantic Web. In this transitional phase, the Web is becoming much more data-centric. The idea of ‘linked data‘ also is a component of this transition, but is more precise in meaning because by definition the data must be expressed as RDF in order to aid interoperability.

The challenge is to convert existing Web pages and data into the structured Web with every resource accessible via an unambiguous URI. Insofar as this conversion also occurs to RDF, it will promote linked data interoperability.

Transitions of such a profound nature — even if short of the full vision of the semantic Web — create the need for new language and terminology to aid understanding and communication. Sometimes, as well, longstanding terms and practices may need to be refined or challenged. In any event, notions of simplistic versioning such as ‘Web 3.0‘ add little to understanding and communication.

Let’s Begin with Data Structure

Independent of the Internet or the Web, let’s begin our discussion about the nature of structure in its application to data [2,3]. Peter Wood, a professor of computer science at Birkbeck College at the University of London, provides succinct definitions of the “structure” of various types of data [4]:

- Structured Data — in this form, data is organized in semantic chunks or entities, with similar entities grouped together in relations or classes. Entities in the same group have the same descriptions (or attributes), while descriptions for all entities in a group (or schema): a) have the same defined format; b) have a predefined length; c) are all present; and d) follow the same order. Structured data are what is normally associated with conventional databases such as relational transactional ones where information is organized into rows and columns within tables. Spreadsheets are another example. Nearly all understood database management systems (DBMS) are designed for structural data

- Unstructured Data — in this form, data can be of any type and do not necessarily follow any format or sequence, do not follow any rules, are not predictable, and can generally be described as “free form.” Examples of unstructured data include text, images, video or sound (the latter two also known as “streaming media”). Generally, “search engines” are used for retrieval of unstructured data via querying on keywords or tokens that are indexed at time of the data ingest, and

- Semi-structured Data — the idea of semi-structured data predates XML but not HTML (with the actual genesis better associated with SGML, see below). Semi-structured data are intermediate between the two forms above wherein “tags” or “structure” may be associated or embedded within unstructured data. Semi-structured data are organized in semantic entities, similar entities are grouped together, entities in the same group may not have same attributes, the order of attributes is not necessarily important, not all attributes may be required, and the size or type of some attributes in a group may differ. To be organized and searched, semi-structured data should be provided electronically from database systems, file systems (e.g., bibliographic data, Web data) or via data exchange formats (e.g., EDI, scientific data, XML).

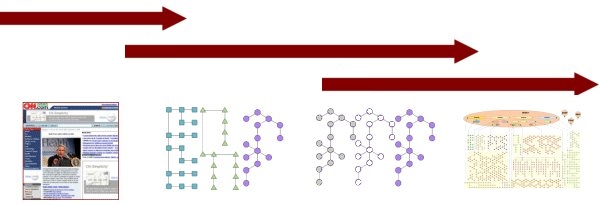

We can thus view data structure as residing on a spectrum (also shown with “typical” storage and indexing frameworks on the top line):

For the past decades, structured data has been typically managed by database management systems (DBMSs) or spreadsheets, unstructured data by text indexing systems such as used by search engines or unindexed in file systems or repositories.

Semi-structured data models are sometimes called “self-describing” (or schema-less) [5]. The first known definition of semi-structured data dates to 1993 [6] by Peter Schäuble: “We call a data collection semistructured if there exists a database scheme which specifies both normalized attributes (e.g., dates or employee numbers) and non-normalized attributes (e.g., full text or images).” More current usage (see the Wood definition above) also includes the notion of labeled graphs or trees with the data stored at the leaves, with the schema information contained in the edge labels of the graph. Semi-structured representations also lend themselves well to data exchange or the integration of heterogeneous data sources.

HTML tags within Web documents are a prime example of semi-structured data, as are text-based data transfer protocols or serializations [7]. Semi-structured data is also a natural intermediate form when “structure” is desired to be extracted from standard text through techniques generally called ‘information extraction’ (IE). For example, here is possible structure shown in yellow as might be extracted from a death notice or obituary [8]:

John A. Smith of Salem, MA died Friday at Deaconess Medical Center in Boston after a bout with cancer. He was 67. Born in Revere, he was raised and educated in Salem, MA. He was a member of St. Mary’s Church in Salem, MA, and is survived by his wife, Jane N., and two children, John A., Jr., and Lily C., both of Winchester, MA. A memorial service will be held at 10:00 AM at St. Mary’s Church in Salem.

This notice contains a great deal of information including names, places, dates and relationships, which once extracted, can be separately indexed or manipulated. Virtually all text-based documents can have similar structure extracted.

The Web has been a prime source of growth of semi-structured data, most often through text-based data serializations [9] and mark-up languages [10].

Depending on point of view or definition, RDF can either be called semi-structured or structured data. It resides squarely at the transition point between these two categories on this structural continuum.

A Variety of Web ‘Resources’

A couple of Web concepts often cause confusion and difficulty for some users: 1) Uniform Resource Locators (URLs) v Uniform Resource Identifiers (URIs); and 2) the concept of “resources” themselves. As it happens, there was a pretty accessible discussion on URIs that was recently posted; I recommend that discussion on that topic. Instead, we’ll focus here on “resources.”

The concept of a resource is basic to the Web’s architecture and is used in the definition of its fundamental elements, including obviously URL and URI above. The essence of the semantic Web parlance, as well, is built around the notion of abstract resources and their semantic properties. The data model and languages of the Resource Description Framework (RDF) squarely revolve around this “resource” concept.

The first explicit definition of resource related to the Web is found in RFC 2396 in August 1998:

However, in the context of the Internet, not all resources so defined (such as a person or a company) can be retrieved, while electronic resources like an image or Web page can. Thus, a first challenge arises in the concept of resource and its locational address: some are actual and physical, others are abstract or referential.

According to Wikipedia’s discussion of resources:

The need to somehow make this distinction between actual or physical resources vs. abstract or referential resources led to much discussion and controversy sometimes known as the httpRange-14 issue [11], resolved by the W3C’s Technical Architecture Group (TAG) in 2005. The TAG defined a distinction between two resource types:

- information resource — this category pertains to the original sense of resources on the Web, such as files, documents or other resources to which a URL can be assigned (including images and non-document media). Though it has been proposed that such resources be designated as “slash” URIs, such as http:///www.example.com/home/index.html, this is not enforceable and some resources in the next category do not adhere. A “slash” URI, however, still is “better practice” (if not “best practice”) for such traditional resources. Note that this category of information resource is very much in keeping with the nature of the early, document-centric Web

- non-information resource — this category is the new one to deal with all of the “abstract” cases such as classes, etc.; this category is especially important to the data-centric Web. As with the other resource category, it was proposed to use the “pound sign” fragment identifiers used by anchor tags, such as http:///www.example.com/data#bigClass, for example, to signal this different resource type, but, again, it is not enforceable and at most could be “better practice.”

A successful HTTP request for an information resource results in a 200 message (“OK”, followed by transfer) from the Web server; if the request is for a resource that the Web server recognizes as existing but of the wrong type requested, the publisher can use the 303 redirect response to provide the correct URI [12].

These resource distinctions are very, very unfortunate in their labeling, if not on more fundamental grounds. It is non-sensical to call one category “information” and the other not, when everything is informational. Moreover, the distinctions bring absolutely no clarity. (Important note: actually, the provenance of the term ‘non-information resource‘ appears to be quite recent, as well as wrong and unfortunate [13]).

However, getting standards bodies to change labels is a long and uncertain task. The approach taken below is to stick with the ‘information resource‘ term, but to provide the alias of ‘structured data resource‘ in place of ‘non-informational resource‘ and to add some additional sub-category distinctions [14].

The Relation Between Resources and Structure

Even though a Web ‘resource‘ has an address scheme and other requirements, these are details and specifics that can mask the fundamental purpose of a resource to act as a “container” for encapsulating information of some sort. This encapsulation is what enables access to its “payload” information (Kingsley’s term) on the Web or the broader Internet via standard protocols (HTTP and TCP/IP). The mechanisms of the encapsulation constitute the details and specifics.

Inherent to the transition from the document Web to the structured Web is the increased importance of that most confusing category: non-information resource. That is because, like fragment identifiers, we are talking about objects more granular (subsidiary) to document-level resources and it is because we are now referencing structure that includes such “abstract” notions as classes, properties, types, namespaces, ontologies, schema, etc.

One paradox in all of this is the very category of resource designed to deal with these data issues is itself called by many a ‘non-informational resource‘. This term is non-sense [13]. We use instead ‘structured data resource.’

There is much that needs to be cleaned up and clarified over time regarding uses and nomenclature regarding resources. However, from the standpoint of the structured Web, we can probably for the time being concentrate on those items shown in bold in this table:

| Information Resource | current standard Web term unstructured and semi-structured data |

||

| Document Resource | text and markup within standard Web pages | ||

| ‘Other’ Resources | non-text resources with a URL (images, streaming media, non-text indexable files) | ||

| Non-information Resource (aka Structured Data Resource) [see text; 13] |

current standard Web term; non-sensical semi-structured and structured data |

||

| Structured Data | all non-RDF data-oriented resources, including non-RDF namespaces, etc. | ||

| Linked Data | all RDF |

Note that the two main resource categories used in practice are maintained. The ‘information resource’ category retains its traditional understanding. From the standpoint of the structured Web, the document resources are the unstructured and semi-structured data content from which information extraction (IE) techniques and software can extract the eventual structure.

The category of document resource likely represents the majority of potentially useful structural content on the Web and is most often overlooked in discussions of linked data or the semantic Web. This content, if subjected to IE and therefore structure creation, then becomes a URI resource better handled as a ‘structured data resource.’

‘Structured data resources‘ (that is, the poorly labeled ‘non-information resources‘) are the building blocks for the structured Web. In all cases, these resources are either semi-structured or structured data. There are two sub-categories of resources in this category, differentiated by whether the structured data is expressed in RDF (or RDF-based languages) or not. All RDF variants are called ‘linked data‘; all other forms are termed ‘structured data.’

Thus, we can see the path to the structured Web taking a number of different branches.

The first branch, and the one necessary for the largest portion of content, is to use a combination of IE techniques to extract entity information from unstructured text or to use structure extraction on the semi-structure of the document [15] to create the structured data resource for that document. Of all variants, this is the longest path, the one least developed, but one with potentially great value.

The second branch is to publish the structured data directly as a resource or to provide access to it through a Web service or API. This is the current basis for most of the structured data resources presently available on the Web. (It is also the outcome of IE for the first branch.)

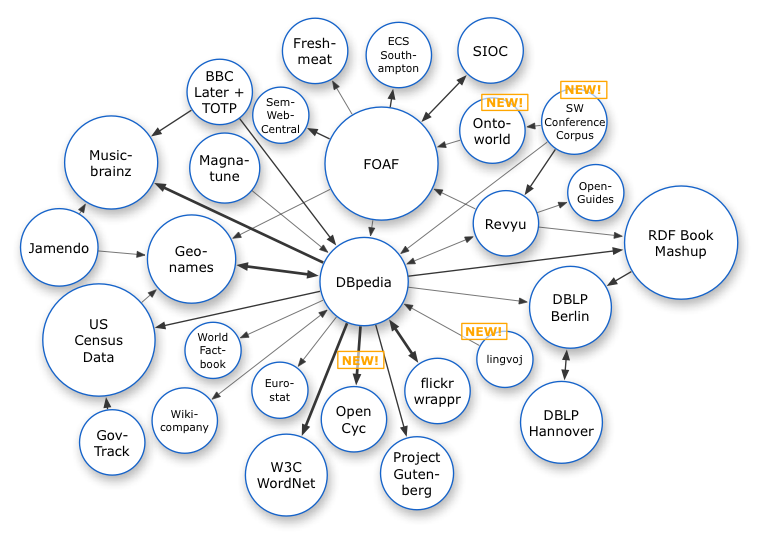

The third branch is really just a complete variant of the other two — ensuring that the structured data resource is available as interoperable RDF linked data. There are two ways to proceed down this branch. One way is for the publisher to create and post the resource directly in a form of RDF. (Though the actual data can be serialized in a variety of ways such as RDF/XML, N3, Atom or Turtle, conversions between these forms is relatively straightforward.) The other way, less direct, is for the publisher or a third-party to convert non-RDF structured data into RDF with the rich and growing list of available ‘RDFizers’ [16].

The Web in Transition

This material, plus the earlier introduction to the structured Web, can now be brought together as a picture of the Web in transition. While there are no real beginning and end points, there is a steady progression from a document-centric Web to one that is data-centric, including the mediation of semantics:

|

|||

| Document Web | Structured Web |

Semantic Web

|

|

| Linked Data | |||

|

|

|

|

|

The basic argument of this series is that we are in the midst of a transition phase — the structured Web — that marks the beginning of the dominance of data on the Web. In its broadest definition, the structured Web has many different data forms and serializations. A subset of the structured Web — namely, linked data — is a direct precursor to the semantic Web with its emphasis on RDF and data interoperability and services.

Another argument of this series is — despite the promise of linked data — that structured data resources in many forms will co-exist and provide alternatives. This diversity is natural. For RDF and linked data advocates, tools are now largely in place to convert these diverse forms. Though the ability to see large-scale availability of RDF data appears clear, the longer-term resolution of mediating heterogeneous semantics remains cloudy.

Brief Glossary

To re-cap, and to aid language and understanding, here is a brief glossary of the key terms used in this discussion:

- dereferencing — the act of locating and transmitting structured data, in a requested format (representation), exposed by a URL

- document resource — a Web resource designated by a URL that contains unstructured and semi-structured data

- information extraction — any of a variety of techniques for extracting structure and entities from content

- information resource — any Web resource that can be retrieved via a URL

- linked data — a structured data resource in RDF that can be obtained via a URI

- non-information resource — this is “any resource” that is not an information resource; preference is to deprecate its use and use structured data resource in its stead

- semantic Web — the Web of data with sufficient meaning associated with that data such that a computer program may learn enough to meaningfully process it

- semi-structured data — data that includes semantic entities that may have attributes or groups, but which are not all required or presented in a set order or in a set size or type; may be embedded or interspersed in unstructured data

- structured data — data organized into semantic chunks or entities, with similar entities grouped together in relations or classes, and presented in a patterned manner

- structured data resource — a structured data resource that can be obtained via a URI

- structured Web — the data-centric Web of structured data resources and structured data in various forms; formally defined as, object-level data within Internet documents and databases that can be extracted, converted from available forms, represented in standard ways, shared, re-purposed, combined, viewed, analyzed and qualified without respect to originating form or provenance

- unstructured data — data can be of any type and does not necessarily follow any format or sequence or rules, can generally be described as “free form;” includes text, images, video or sound

- URI — uniform resource identifier

- URL — uniform resource locator

[1] You will note a heavy emphasis on Wikipedia definitions in keeping with Web usage.

[2] Of course, the word ‘structure‘ has a broad range of meanings; we are only concerned here about data structure and its specific applicability to Web-related information.

[3] Much of the discussion in this sub-section is derived from an earlier AI3 posting, Semi-structured Data: Happy 10th Birthday!, from November 2005; some of the original information is a bit dated. It is also aided by Kingsley’s Structured Data v. Unstructured Data posting from June 2006. That posting notes the frequent confusion and ambiguity between the terms “structured data” and “unstructured data,” and the importance when speaking of structure to keep separate the structure of the data itself (the focus herein), the structure of the container that hosts the data, and the structure of the access method used to access the data.

[4] Peter Wood, School of Computer Science and Information Systems, Birkbeck College, the University of London. See http://www.dcs.bbk.ac.uk/~ptw/teaching/ssd/toc.html.

[5] The earliest known recorded mention of “semi-structured data” occurred in 1992 from N. J. Belkin and Croft, W. B., “Information filtering and information retrieval: two sides of the same coin?,” in Communications of the ACM: Special Issue on Information Filtering, vol. 35(12), pp. 29 – 38, with the first known definition from [6]. The next two mentions were in 1995 from D. Quass, A. Rajaraman, Y. Sagiv, J. Ullman and J. Widom, “Querying semistructured heterogeneous information,” presented at Deductive and Object-Oriented Databases (DOOD ’95), LNCS, No. 1013, pp. 319-344, Springer, and M. Tresch, N. Palmer, and A. Luniewski, “Type classification of semi-structured data,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Very Large Data Bases (VLDB). However, the real popularization of the term “semi-structured data” occurred through the seminal 1997 papers from S. Abiteboul, “Querying semi-structured data,” in International Conference on Data Base Theory (ICDT), pp. 1-18, Delphi, Greece, 1997 (http://dbpubs.stanford.edu:8090/pub/1996-19) and P. Buneman, “Semistructured data,” in ACM Symposium on Principles of Database Systems (PODS), pp. 117-121, Tucson, Arizona, May 1997 (http://db.cis.upenn.edu/DL/97/Tutorial-Peter/tutorial-semi-pods.ps.gz). Of course, semi-structured data had existed prior to these early references, only it had not been named as such.

[6] P. Schäuble, “SPIDER: a multiuser information retrieval system for semistructured and dynamic data,” in Proceedings of the 16th Annual International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, pp. 318 – 327, 1993.

[7] Such protocols first received serious computer science study in the late 1970s and early 1980s. In the financial realm, one early standard was electronic data interchange (EDI). In science, there were literally tens of exchange forms proposed with varying degrees of acceptance, notably abstract syntax notation (ASN.1), TeX (a typesetting system created by Donald Knuth and its variants such as LaTeX), hierarchical data format (HDF), CDF (common data format), and the like, as well as commercial formats such as Postscript, PDF (portable document format), RTF (rich text format), and the like. One of these proposed standards was the “standard generalized markup language” (SGML), first published in 1986. SGML was flexible enough to represent either formatting or data exchange. However, with its flexibility came complexity. Only when two simpler forms arose, namely HTML (HyperText Markup Language) for describing Web pages and XML (eXtensible Markup Language) for data exchange, did variants of the SGML form emerge as widely used common standards. The XML standard was first published by the W3C in February 1998, rather after the semi-structured data term had achieved some impact (http://www.w3.org/XML/hist2002) Dan Suciu was the first to publish on the linkage of XML to semi-structured data in 1998 (D. Suciu, “Semistructured data and XML,” in International Conference on Foundations of Data Organization (FODO), Kobe, Japan, November 1998; see PDF option from http://citeseer.ist.psu.edu/suciu98semistructured.html), a reference that remains worth reading to this day.

[8] David Loshin, “Simple semi-structured data,” Business Intelligence Network, October 17, 2005. See http://www.b-eye-network.com/view/1761. This example is actually quite complex and demonstrates the challenges facing IE software. Extracted entities most often relate to the nouns or “things” within a document. Note also, for example, how many of the entities involve internal “co-referencing,” or the relation of subjects such as “he” or clock times such as “10 a.m” to specific dates. A good entity extraction engine helps resolve these so-called “within document co-references.”

[9] Example text-based data serializations and formats used on the Web include Atom, Gdata, JSON, N3, pickle, RDF/XML, RSS, Turtle, XML, YaML.

[10] Example mark-up languages used on the Web include HTML, Wikitext, XHTML, XML.

[11] It was called the httpRange-14 issue by virtue of the agenda label at the TAG’s meetings.

[12] Of course, nothing compels the publisher to provide these instructions, but they are integral to “best practices” and publishers desirous of attracting consumers have incentives to follow them.

Depending on the nature of the information resource, an HTTP GET returns a 200 OK status and sends the resource (for example a request for a Web page or an RDF file) if the request is for the correct type. If the request is for the wrong type, the publisher can include in the header a 303 (See Other) redirect response to send the requester to the appropriate information resource URL. If the request is for an unknown URI or resource, a variety of 4xx error responses may result. (See further [13].)

One advantage of posting structured data resources as RDF- linked data is that this redirect can be sent to a REST-style Web Service that does a best-effort DESCRIBE of the resource using SPARQL. Since SPARQL is a query language, protocol, and results representation scheme, the redirect can come in the form of a URL that can directly query the structured data resource. In this manner, large structured data resource data sets can act as ‘endpoints’ for context-specific information linked anywhere on the Web.

[13] The report of the TAG’s 2005 ‘compromise solution’ was reported by Roy Fielding, with his public notice reproduced in full:

<TAG type=”RESOLVED”>

“http” URIs for any resource provided that they follow this

simple rule for the sake of removing ambiguity:

2xx response, then the resource identified by that URI

is an information resource;

303 (See Other) response, then the resource identified

by that URI could be any resource;

4xx (error) response, then the nature of the resource

is unknown.

</TAG>

I believe that this solution enables people to name arbitrary

resources using the “http” namespace without any dependence on

fragment vs non-fragment URIs, while at the same time providing

a mechanism whereby information can be supplied via the 303

redirect without leading to ambiguous interpretation of such

information as being a representation of the resource (rather,

the redirection points to a different resource in the same way

as an external link from one resource to the other).

Note that point “a” discusses an “information resource,” with the contrasting treatment in point “b” as potentially “any resource”.

To my knowledge, the first that the unfortunate term ‘non-information resource’ was introduced to cover these point “b” conditions was in a draft (that is, unofficial) TAG finding from two years later, in May 31 of this year, “Dereferencing HTTP URIs.” Besides its unfortunate continuation of the ‘dereferencing’ term (a discussion for another day), it introduces the even-worse ‘non-information resource’ terminology. That draft TAG finding in Sec 2 talks about ‘information resources’ (as does the 2005 TAG finding), and in Sec 3 about ‘other Web resources’ (or the “any” category from the 2005 notice). In Sec 4, however, the document switches from ‘other Web’ to ‘non-information’, which is then continued through the rest of the document.

It is not too late for the community to cease using this term; our replacement suggestion is ‘structured data resource.’

[14] You may also want to see, Leo Sauermann, Richard Cyganiak, and Max Völkel “Cool URIs for the Semantic Web,” or Dan Connolly, “A Pragmatic Theory of Reference for the Web.”

[15] Web documents are typically semi-structured with embedded tag, metadata, and presentation structure in such things as headers, tables, layouts, labels, dropdown lists, etc. For the unstructured text content, traditional information extraction techniques are applied. But for the semi-structure, various scraping or extraction techniques may either be crafted by hand or be semi-automatically or automatically applied through regular expression processing, pattern matching, inspection of the Web page DOM or other techniques. One posting in this structured Web series is to be devoted to this topic.

[16] There is an impressive and growing list of data conversion protocols and tools, most which support multiple input and output forms, including RDF and various serializations of RDF. This list includes Virtuoso Sponger, GRDDL, Babel, RDFizers, general converters, Triplr, etc. One posting in this structured Web series is to be devoted to this topic.