Introducing the Open Source ‘DocWiki’ System

In the first part to this series, we began with the argument that open source software alone was not sufficient to meet the required acceptance factors in the enterprise. As a guiding way to create the right mindset around these issues we shared the saying that we have adopted at Structured Dynamics that, “We’re successful when we are not needed.”

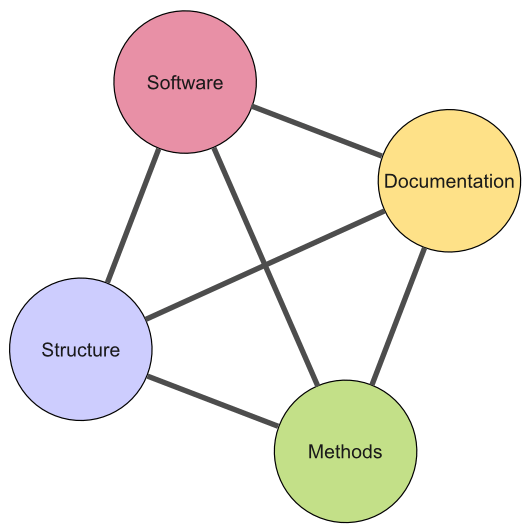

In the second part of this series we described the four legs of a stable, open source solution. These four legs are software, structure, methods and documentation. When all four are provided, we termed this a total open solution.

Now, in this third and concluding part to our series, we introduce the open source documentation and methodology system called ‘DocWiki’. It complements the base open source software, in the process completing the conditions for a total open solution.

Though we call this system ‘DocWiki’, it is not meant to be a brand or particular product description for what Structured Dynamics is offering. Rather, ‘DocWiki’ is merely a placeholder name for a generic, open source system and knowledge base that can be downloaded, installed, branded, modified and extended in whatever way the user sees fit. ‘DocWiki’ is a baseline documentation and methodology “starter kit” that can be dressed up in new clothes or packaged and named in whatever manner best suited to a given deployment.

In describing the major components of this ‘DocWiki’ system we will again use our Citizen Dan initiative [1] as we did in Part 2. This gives us a real use case, though the same approach is applicable to any open source information management initiative by enterprises.

We call the specific version of the ‘DocWiki’ used in the case of Citizen Dan the ‘CIS DocWiki‘ (for community indicator systems), specific to the domain and local government focus of Citizen Dan. Similarly, the structured vocabulary and ontology that guides the system is the MUNI ontology. For other information development initiatives, the specific content of these components would be swapped out for ones appropriate to that initiative.

Overview of the ‘DocWiki’ System

A number of desires and objectives intersected to guide the design of the ‘DocWiki’ system. We wanted:

- A consolidated knowledge base with complete, turnkey implementation content

- A collaborative document authoring system with authoring tools comfortable to most knowledge workers

- A version control system to enable rollbacks and restoration of prior official versions

- A system that would enable and facilitate the collection and import of relevant content; in our own case, that included widely distributed internal content in many forms and locations plus relevant external content (such as defined items in Wikipedia)

- A document management framework that would allow existing content to be mixed, combined and re-purposed for different uses, from training to marketing collateral

- A single source publishing system that would allow content to be published as paper documents, PDFs, Web pages and the like

- A system that could be easily themed, skinned and branded, tailored for any given deployment or circumstance, and

- A system built entirely from open source components and with content that had no restrictions on use or re-use.

In first formulating this design, our assumption was the major building blocks would be an open source document management system linked with some form of version control. Though we think such a formulation could work OK, our exposure to the MIKE2.0 methodology actually caused us to re-look at and re-think a wiki-based approach. Ultimately the trump card that decided the design for us was familiarity and ease-of-use.

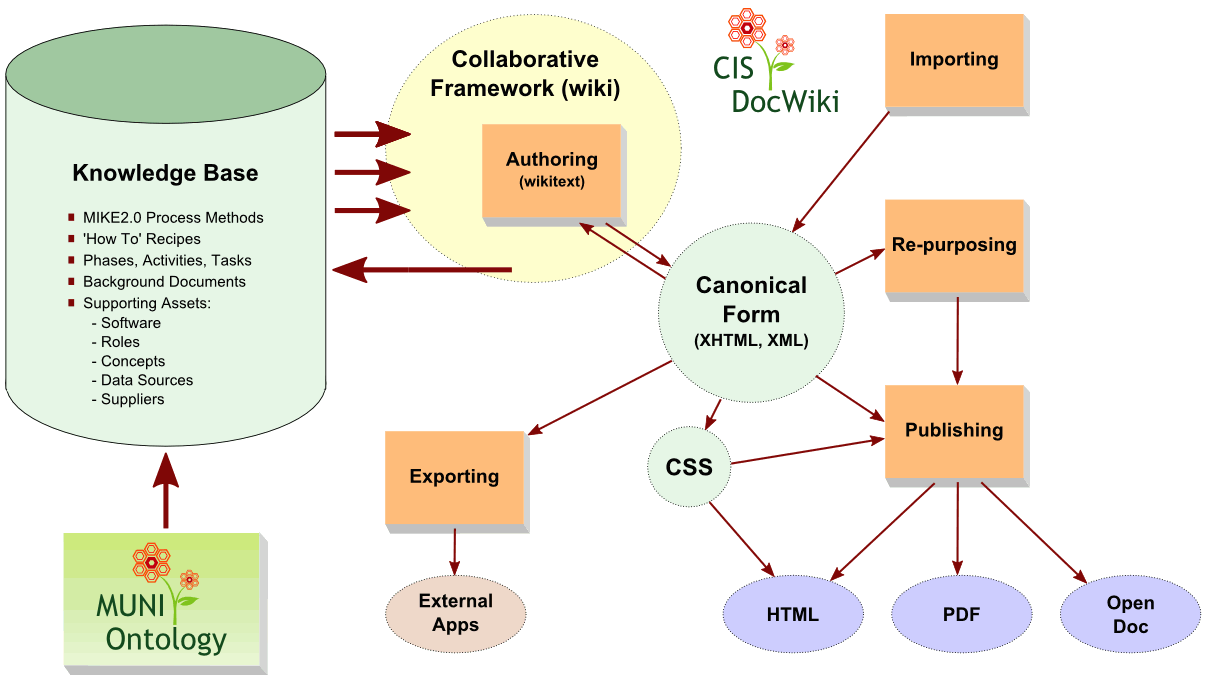

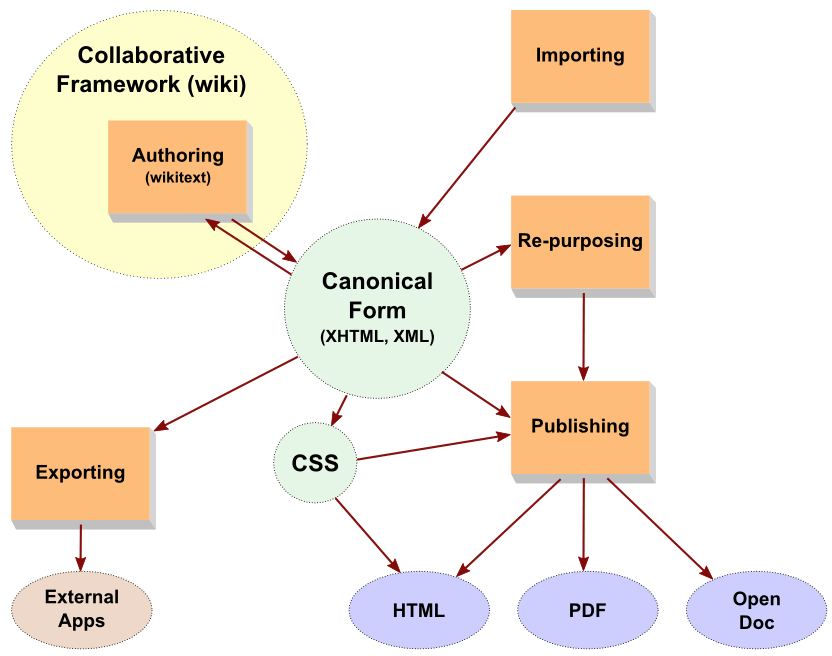

The resulting architecture of the full ‘DocWiki’ system is shown below:

(click for full size)

What is cool about this design is that a single software download install with a few extensions (Mediawiki, the Wikipedia software, plus some standard extensions and judicious use of Semantic Mediawiki) and a single loadable database are all that is required to transfer and install the ‘DocWiki’ system.

To better describe this system, we will focus on three major interconnecting pieces in this architectural diagram: the knowledge base; the vocabulary and structure (ontology); and the authoring and publishing system (wiki).

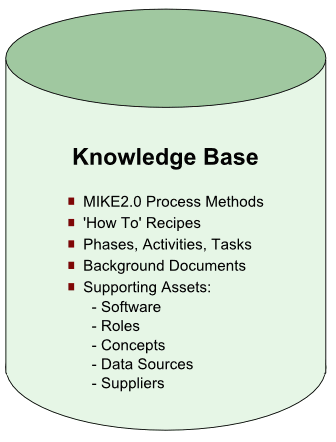

The ‘DocWiki’ Knowledge Base

The pre-loaded content for the ‘DocWiki’ system comes from its knowledge base. This is provided as a text-exported MySQL database that can be modified en masse before loading (such as substituting ‘YourName’ for ‘DocWiki’). The exemplar upon which this knowledge base is modeled is the MIKE2.0 framework.

MIKE2.0 (Method for an Integrated Knowledge Environment ) provides a comprehensive methodology that can be applied across a number of different projects within the information management space. MIKE2.0 provides an organized way to describe the why, when, how and who of information management projects. Via standard templates and structures, MIKE2.0 provides a consistent basis to describe and manage these projects, and in a way that helps promote their interoperability and consistency across the enterprise.

MIKE2.0 has a generalized methodology and set of templates applicable to initiatives, the phases, activities and tasks to undertake them, and supporting assets. Supporting assets can range from glossaries and definition of terms and concepts to very specific technical documents or background material. The entire system is logical and applies a consistent design and organizational structure and categories.

For our purposes, we wanted a complete, turnkey content knowledge base. This meant that we needed to accommodate all forms of project management and guidance, ranging from specific “how-to” and technical discussions to the entire suite of background and supporting material. The scope of this knowledge content is defined as what a new person assigned a lead or implementation responsibility would need to read or master.

As a destination site MIKE2.0 is quite broad: it embraces the ability to model virtually any information management initiative. This makes MIKE2.0 an invaluable source of structure and methodology guidance, but also results in it being quite limited in the specific how-tos associated with any given initiative. I have earlier spoken about the structure of MIKE2.0 and in particular its applicability to the semantic enterprise.

The strength of MIKE2.0, however, is that its structure can be grabbed and quickly applied to form an organizational and structural basis for filling out the knowledge base for any specific information development initiative. And, that is exactly what we did with the ‘CIS DocWiki.’

MIKE2.0 hosts and maintains its project-related structure in Mediawiki (with some extensions). Combined with its templates, this provides a rapid-start baseline for beginning to tailor and flesh out the specific details for a given information management initiative. Thus, after copying broad aspects of the MIKE2.0 system into the incipient ‘DocWiki’, it was relatively straightforward to let the existing structure and templates of MIKE2.0 guide next steps.

As of today’s date, the ‘CIS DocWiki’ contains about 300 substantive articles, a complete activity and tasking structure, and various re-usable templates based on Semantic Mediawiki for structured and consistent access and retrieval. New tasks and structure can be readily added to the system. Existing structure or content can be deleted or marked as archive for non-display. We are still gathering all requisite content pieces, and anticipate by first public release that the baseline knowledge base will include 2x to 3x the scale of its current content.

For new ‘CIS DocWiki’ (or Citizen Dan-based) deployments, this means the knowledge base can be completely modified and extended for local circumstances. The set-up of the Mediawiki instance is separate from the loading or modification of the knowledge base, which means the look-and-feel of the entire system, not to mention user rights and permissions, can also be readily tailored for local requirements.

The core content of the ‘CIS DocWiki’ and its basis in a set structure and methodology (derived from MIKE2.0) means that the knowledge base is also adaptable for other broader information development areas, especially in the semantic enterprise or semantic government arenas. Thus, while Structured Dynamics is first releasing the ‘CIS DocWiki’ in the context of Citizen Dan and semantic government, we also are developing a parallel instance for the Open SEAS approach to the semantic enterprise.

The approach taken here is somewhat different than the standard wiki use. As experts, we are basically sole authoring (with contributions from selected collaborators and our clients) the starting basis of the knowledge base. Unlike many wikis, this enables us to be quite consistent in content, style, and organization. Such an approach allows us to present a coherent and complete starting content and methodology foundation. However, once delivered and installed for a given deployment, its users are then free to extend and change this knowledge foundation in the standard wiki manner. Whether those subsequent extensions are free-form or more tightly controlled and managed is the choice of the new deployment’s administrators.

The Supporting MUNI Structure

Strictly speaking, the vocabularies and structures (including, of course, ontologies) that drive our semantic government or semantic enterprise offerings are also part of the knowledge base. And, in fact, many of these aspects, especially related to the actual operating of the instances, are included as part of the standard knowledge base.

However, the applicable domain ontology itself is separately maintained. Descriptions of how to use and modify such ontologies are part of the general ‘DocWiki’ knowledge base, but the ontology is not. This arm’s length-separation is done to acknowledge that the ontology has independent use and value apart from the knowledge base or the software (Citizen Dan, in this case) that is the focus of it.

In the Citizen Dan instance, this structure is the MUNI ontology. MUNI is a general local government domain ontology that can find use in a broad array of circumstances, using or not Citizen Dan. Thus, like other ontologies developed and maintained by Structured Dynamics, such as BIBO (the Bibliographic Ontology), the ontology itself and its documentation, discussion forums and use cases are maintained separately.

The first release of MUNI is still under development and will be released this summer.

The Wiki/Publication Portion of ‘DocWiki’

The software framework that hosts and manages all of this content is the Mediawiki software, originally developed for Wikipedia. This framework is supported by a number of standard extensions packaged with the ‘DocWiki’ distribution. One of the more notable extensions is Semantic Mediawiki. Mediawiki also is the wiki framework underlying MIKE2.0, so content sharing between the systems is straightforward.

The Collaborative Wiki Portion

The first use of the ‘DocWiki’ is to add new content to the knowledge base and to modify or extend what is provided in the baseline. For straight authoring, ‘DocWiki’ offers the standard wikitext basis for content entry and editing, as well as the WikED enhanced editor and the FCKEditor WYSIWYG rich-text editor. Each of these may be turned on or off at will.

All of the baseline content is fully organized and categorized via a standard structure. Pre-existing templates aid in entering new content in specific areas consistently or in providing standard administrative ways of tagging content for completeness or need for editorial attention. Tasks and concepts, in particular, follow set ways of entry and description. These set templates, some forms-based and some derived from Semantic Mediawiki, are also tied into automatic internal scripts for listing and organizing various items. So long as new material is entered properly, it will be reflected in various stats and listings. Unlike sole reliance on Semantic Mediawiki, the ‘DocWiki’ approach is a mix of standard wiki categories and semantic types. Both are used for effective organization of the knowledge base.

Besides the knowledge base of domain content and “how-to”, the system also comes pre-packaged with many wiki “how-to” and best practices guidance for using the system effectively and consistently. Of course, a given deployment may or may not enforce all of these practices. A poorly administered instance, for example, could degenerate fairly quickly and lose the native structure and organization of the baseline system.

As with standard wikis, there is a history of prior page revisions that gives the system rollback and version control. Mediawiki has a pretty good user access and permissions framework ranging from access, reading, editing and to uploads.

Besides the standard and required extensions, ‘DocWiki’ also comes packaged with the necessary settings and configuration files to operate “out-of-the-box” in its designed baseline mode. Of course, these settings, too, can be changed and modified by site administrators, and ‘DocWiki’ also includes guidance on how to do that.

The Publication Portion

A little known but highly useful part of the Mediawiki API allows direct export of XHTML content [2]. Then, with minor XSLT conversion templates, it is possible to strip out wiki-specific conventions (such as the editing of individual sections) or to create straight XML versions. When this is combined with the use of internal ‘DocWiki’ CSS style sheets that impose some clean and semantic style identifiers, a common canonical output basis for content is possible.

From that point, a given deployment may use its own CSS styles to theme output content. Output Web pages (XHTML) or XML files then can be processed using existing and accurate utilities to produce PDF or *.doc documents. Then, with systems such as OpenOffice, an even wider variety of document formats can be produced. These facilities mean that the ‘DocWiki’ can also act as a single-source publishing environment.

In its initial release, re-purposing ‘DocWiki’ content into other presentations (for example, combining sections from multiple pages into a new document as opposed to re-using existing pages as is) will require creating new wiki pages and then cutting-and-pasting the desired content. However, it should also be noted that both DocBook and DITA have been applied to Mediawiki installations [3]. It should be possible to enable a more flexible re-purposing framework for ‘DocWiki’ moving into the future.

When Available

The ‘CIS DocWiki’ is meant to accompany the first release of Citizen Dan, likely by the end of summer. The MUNI ontology will also be released roughly at the same time. At release, the ‘CIS DocWiki’ is anticipated to have on the order of 500-800 baseline content and “how to” articles.

Depending on time availability and other commitments, Structured Dynamics will also be using this information to build a semantic government composite offering to MIKE2.0. We will be contributing this new offering for free, similar to what we have done earlier for a semantic enterprise offering.

Subsequent to those events, we will then be modifying the ‘CIS DocWiki’ for the semantic enterprise domain. Much of the necessary content will have already been assembled for the ‘CIS DocWiki’.

Conclusions and Applicability

Paradoxically, while developing such knowledge bases and systems such as ‘DocWiki’ appears to be extra work, from our standpoint as developers it is useful and efficient. Structured Dynamics already researches and assembles much material and tries to “document as it goes.” Having the ‘DocWiki’ framework not only provides a consistent and coherent way to organize that information, but it also helps to point out essential gaps in our offerings.

The ‘DocWiki’ delivers the methods, documentation and portions of the structure to a total open solution. The ‘DocWiki’ is the primary means — along with software development and accompanying code-level and API documentation, of course — for us to fulfill our mantra that “We’re successful when we are not needed.” As we pointed out in Part 1 of this series, we really think such an attitude is ultimately a self-interested one. The better we can address the acceptance factors in the enterprise for our offerings, the more opportunities we will gain.

We would like to think that other enlightened open source software developers, especially those in the semantic space but certainly not limited to them, will see the wisdom of this four-legged foundation to total open solutions. Up until now, pragmatic guidance for what it takes to create a complete open source offering to businesses and enterprises has been lacking.

The tools, methods, and workflows all exist for making total open solutions real today. All of the pieces are themselves open source. There are many useful guides for best practices across the pipeline. It is just that — prior to this — no one apparently took the time to assemble and articulate them. We think this three-part series and some of the “how to” guidance in the ‘DocWiki’ system can help fix this oversight.

Ultimately, with wider adoption by developers, goaded in part by demands of the marketplace for them, we would hope that additional innovations and ideas may be forthcoming to improve the industry’s ability to offer total open source solutions. Adding just a small bit of attentive effort to how we organize and package what we know is but a small price to pay for greater acceptance and success.

I think it fair to argue that well-documented open source code generally out-competes poorly documented code. In most circumstances, well-documented open source is a contributor to the

I think it fair to argue that well-documented open source code generally out-competes poorly documented code. In most circumstances, well-documented open source is a contributor to the