To Combat a Decline in Mindshare, Follow What is Pragmatic

To Combat a Decline in Mindshare, Follow What is Pragmatic

A secret of the semantic Web community is that energy, innovation and participation have slipped over, say, the past three or four years. This has been obvious for some time. I began collecting statistics on such things as prevalence in Google searches, attendance at SemTech or xSWC meetings, postings to user groups, blog postings, heck, even stupid and lengthy controversies on the mailing lists, or the sale and then sale and then sale of SemTech itself.

Fortunately, I realized that my observation of a decline did not depend on having documentary backup: the trend was obvious. So, I could stop collecting time-sucking statistics. I’m sure many of the participants in the formation of the semWeb know exactly of this decline in energy and focus of which I speak.

Other endeavors have kept me from worrying too much about such matters, but recent griping in public forums about the state of the semantic Web got me again thinking about premises and the state of semantic technologies. Such re-thinks are useful because they help put current circumstances into context, and because they help guide how to spot emerging opportunities.

While I am not feeling overwhelmingly passionate about such matters, there does appear to be a villain in this story, what I might term the FYN crowd [1]. But, like all good villains and stories, villainy is mostly a matter of context, with the winners being the ones writing the history. So, accept my thoughts as arising as much from my own worldview as from anything else . . . .

Galileo’s Balls

Once one embraces an intellectual domain with the premise of semantics, then meaning and context a priori become first citizens. Depending on viewpoint, what the semantic Web means to one individual can differ substantially from another individual. Moreover, the space becomes a sort of cipher for expressing any worldview, legitimately. For example, one tension at the heart of the semantic Web enterprise has been bottom up v top down; another has been anything goes v more structure and formalism. Hot buttons arise when worldviews differ, as they always surely do. The semantic Web is no exception.

Yet the stated bases for these semantic Web hot buttons, I would claim, are simplistic. What really occurs in the semantic technology space is something more akin to the Galileo thermometer, multiple viewpoints finding multiple resting points. Only in the semantic Web case, the natural resting points don’t just simply occur along a single dimension of, say, formalism, but other viewpoints as well. So, what we end up with is something more akin to a 3D- or multi-dimensional column. There are an infinite number of resting points in reasoned discourse.

Why should this be strange or threatening? Of course, upon inspection, it is not. The understanding that needs to arise is that semantics is truly about differences at all levels of human experience, perceptions and language. A pragmatic semantics must reflect this reality.

I don’t think that these sentiments will ever translate into precision or algorithms. But they can be modeled approximately with algorithms and refined with judgment. Much of their essence can also be captured by ontologies. These are viewpoints that can be captured in silico and used to help humans make better decisions. Semantics are essential to these prospects. At the heart of any pragmatic semantics must be an accommodation of viewpoints and terminology.

The real point in all of this — actually, also the major reason for semantic technologies in the first place — is that for any topic of normal human discourse there is a variety of viewpoints. Only a system expressly designed to respect these differences can be an effective digital means of interoperability.

Tribal Diversities

There are many tribes within the semantic technology space. Academic researchers are the most visible tribe. Because of funding nuances and general interest and tradition (though there are real differences between the US, Queen’s countries, EU or Asia), academics have — and sometimes continue to — set the tone for the semantic Web community. This has been useful to establish a coherent and (generally) logical basis to the underpinnings of the semantic Web. But most in the community would also acknowledge this basis is not sufficient to achieve commercial breakthrough.

In the US, there is a strange mix, with many semantic researchers flying below the radar, because they work for the three-letter intelligence agencies. Also, there is a very strong biomedical community, often funded from the National Library of Medicine. The biomedical community has been an exemplar innovator. Because of this community’s efforts, we now can see how an entire domain — biomedical — can develop and leverage ontologies, establish common vocabularies or standards, or cooperate on tools development. There is no public community more advanced in semantic techology developments than the biomedical one.

Another tribe in this space is the successful hunter, able to use semantic technology capabilities to attract and secure paying customers. Most of the activities of these tribe members is hidden from view, because their paying efforts are by nature infrastructural and concentrated on enterprise and commercial customers. But, also, many individuals within this tribe actively contribute to public efforts and conferences. Many of the more visible semantic technology companies, including my own, occupy this space.

But the most enriched tribe of the semantic Web has been the background semantic orchestrator, generally through infrastructure-based initiatives like broadscale knowledge representation, statistical analysis of massive text corpora, well-considered ontologies, or knowledge structures. The semantic efforts of the search engine vendors, including Bing and Google’s knowledge graph, are members of this tribe, as is Siri, now part of Apple.

These differences in market focus and visibility have tended to play out in expected ways. Academic researchers, Web enthusiasts and those committed to open data have been most vocal about “linked data”. They tend to be the more visible participants in semantic Web mailing lists and forums. Casual followers of the semantic technology space, or those new to it, mostly hear these same voices. By default, the apparent health and status of the semantic Web is more-or-less defined by these voices.

When I said in the intro that the semantic Web has slipped over the past few years, that perception is mostly the result of the lowered volume and fewer messages coming from the vocal tribe. But there are two problems with the accuracy resulting from that. The first, as argued above, is that the vocal and visible linked data advocates are not the only representatives of the community. And, the second, which I’ll get to in a moment, is that the vocal community’s prescriptions for the semantic Web, in my opinion, are no longer the most meaningful ones.

Branding, Terminology and Marketing Messages

Many early proponents of the semantic Web, I think it fair to observe, would say that two positioning mistakes (from their perspective) have kept the paradigm from grabbing greater hold. The first reason often cited is the use of XML as the initial syntax of RDF. At first blush, I agree with this observation, given that when I was first entering into the dark chambers of the semantic Web it was at times difficult to separate XML from RDF. Today, though, most semWeb practitioners prefer the use of alternative serializations. I personally don’t think that any difficulties that semantic Web understanding and adoption may pose today are any longer influenced by a decade-old XML confusion. In Web years, these are eons.

Many early proponents of the semantic Web, I think it fair to observe, would say that two positioning mistakes (from their perspective) have kept the paradigm from grabbing greater hold. The first reason often cited is the use of XML as the initial syntax of RDF. At first blush, I agree with this observation, given that when I was first entering into the dark chambers of the semantic Web it was at times difficult to separate XML from RDF. Today, though, most semWeb practitioners prefer the use of alternative serializations. I personally don’t think that any difficulties that semantic Web understanding and adoption may pose today are any longer influenced by a decade-old XML confusion. In Web years, these are eons.

The second reason seems to have been the flat-out retreat from “semantic Web” terminology. The conscious decision to switch to the “linked data” branding began in earnest about 2008. I find this shift interesting. I think it relates to looking to the wrong measures of success. What seemed like a clever re-branding at that time has both set the focus in the wrong direction and consequently set the wrong targets for measuring success.

In the areas of standards and movements, moral authority, suasion and prominence often become the bases for who is viewed as “owning” a new concept. There has been much of this posturing around the “semantic Web” and “linked data”, with parry thrusts from “Web 3.0” and “big data” and “open this or that”. So, I’m not surprised that branding many of the concepts of the semantic Web with a new term — “linked data” — was pushed and took hold. But why original semantic Web advocates adopted this term and its shift in focus from an ecosystem to data representation and exchange does surprise me.

The strange thing, in my opinion, is the monadic emphasis on “linked data” that acts to partially kill the semantic Web minding. Whether by design or fallout, “linked data” inexorably shifts the focus to how data is represented and transmitted. It is a royal pain in the ass for publishers to publish “linked data” and then, when done, there is surprisingly little consumption of it. The MusicBrainz announcement it was dropping RDFa last week is telliing [2]. We are seeing the representation of structured Web data being driven on other bases, as evidenced by the success of JSON, something that linked data enthusiasts have only lately come to embrace, and the schema.org initiative of the major search engines.

Once linked data was raised as the lead banner, other branding messages followed. The first add-on message was “follow-your-nose”. FYN represents clcking from link to link following data references of interest on the Web [1]. In order for that be facilitated, but also as a means to clear up some confusions about linked data, the quality standard of “5-star linked data” was also put forth. To achieve all five stars, linked data should conform to open standards such as RDF and link to other data for context [3].

Today, on virtually all “official” semantic Web forums you will see mention of the brands of linked data, FYN, 5-star linked data, and open data. Publishing of data according to best practices that enables global links from datum to datum across the Giant Global Graph has become the sort of gold standard associated with this new branding.

What is the Measure of Success?

Success is always measured against our premises and values. In the case of the vocal tribe, the premises and values relate to linked and open data. By these measures, the semantic Web is a mixed bag. On the positive front, many laudable sources of quality data — most recently the Getty Museum [4], but also the Library of Congress and arts and humanities publishers across Europe, but also including many science realms beyond biology, and of course hundreds of others made famous by the LOD cloud [5] — are published as linked data. or in the process being so. Open data sets are coming from government at all levels [6].

On the negative front, the growth of pubished linked data has fallen behind the pace of publishing structured data in general, and notable evidence for where the consumption of linked data has made a difference is pretty hard to find. Linked data advocates only rarely discuss integration with “closed”, proprietary data or enterprise use, integration and realities. Shitty sameAs assertions abound everywhere. Markets find it hard to get excited when the arguments and reference frameworks don’t relate well to their actual problems and pain points. DBpedia can only go so far, and a mountain of links to it without relevance, context or quality is just so much more noise [7].

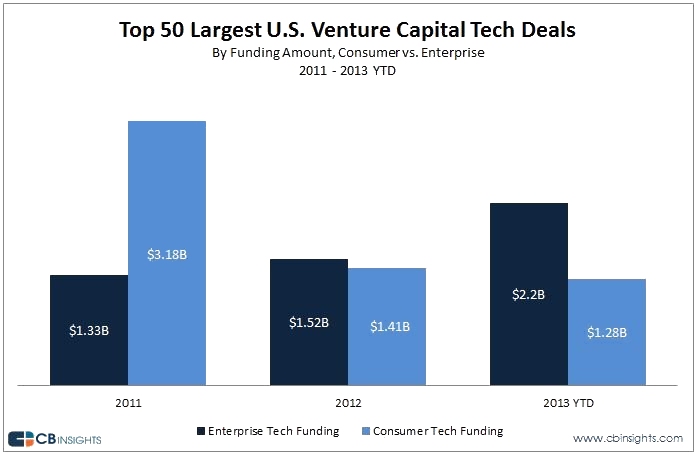

The point here is not to mount a screed against linked data, but to caution: Be careful how you brand yourself. By the measures of growth and penetration and uptake of linked data, moreover linked open data, the semantic Web space is generally not attracting developer interest, media attention or venture dollars. I hope the release of meaningful linked data continues, but setting that goal as the measure of the semantic Web’s success is selling the wrong product.

Rather than setting a FYN objective as to whether our semantic technology efforts to date have been a success, I suggest we adopt a “follow the money” (FT$) premise. Who is investing or making money off of this stuff, and how and why? Herein lies a different measure of success.

If we look to the approaches taken by those making money in this market, we find that the:

- Challenges of meaningful connections

- Interoperability

- Integration across document and structured data

- Discovering new patterns and relationships

- Facilitating semantic understanding across disparate communities and legacy data sources, and

- Providing quality characteristics for new entities,

are where the bucks are being made. These activities are all at the heart of the knowledge worker’s job responsibilities. Even the earliest advocates of the semantic Web must have had aspirations that the semantic Web had the promise to address these meaningful challenges.

Another secret to systems like Freebase, Google knowledge graph, Bing, Watson, Siri, or similar innovations is their use and reliance on Wikipedia, at least in their formative stages. Though often DBpedia was the structural form of ingest, the core basis of these systems’ capabilities comes from content — Wikipedia — the access to which was only made easier via DBpedia.

The sentiment to follow the money is not a sell out or a political statement. It is a recognition that work worth doing is work others appreciate and are willing to pay for. It is the best signal amidst the noise of what is valuable to work on.

It’s Time for the Side B Hit

I’ve been a fairly active participant in the semantic Web for nearly 10 years. I sometimes have the image of an aspiring music artist from the ’50s or ’60s arguing with the record execs which song should be the favored Side A cut on the 45. The visible voices of the semantic Web want to push FYN and linked data as Side A, but it really isn’t selling, according to the advocates’ own success measures.

The Side B of interoperability, RDF and OWL is not just “filler” to the main promotion, but where I clearly think the hit resides. Some have heard that track, buy it, and are enthused about it. It would be nice if the record execs could see what is right before their face and begin promoting it as well.

FYN and its vocal proponents risk the perception of failure of the semantic Web enterprise from the simple fact of putting linked data front and center. Sure, it is a good approach with potentially rich information so long as you can trust the source both for the content itself and the quality of its RDF expression. No one is arguing with that.

But SGML and ASN.1, one could argue, in similar veins, amongst actually dozens of others, were great and useful notations, yet are now mostly historical footnotes. If a trusted source is going to serve me up 5-star linked data, I will take it. Yet the truth is I would take structured data in any form from a trusted source, but take no linked data from an unknown source or one with poor linkages. We spend much time looking at these issues for our clients, and it is the rare linked data set that becomes part of our solution. Even then, we carefully scrutinize all assumed connections.

The Side B semantic Web of vetted and interlinked, interoperable data organized by competent graphs is the winning side. It is the only location where true economic transactions are taking place around the semantic Web. To understand where the semantic Web makes sense, follow the Side B money to your answers.

The insight gained from a FT$ approach clearly points to the failure of FYN. I say, do linked data if you can, it is the best ingest format around. But don’t get too hung up on that. Spend your time figuring out how to bridge meaningful gaps in semantics or data across any enterprise, global or local. Information is not truffles, and following your nose is not the primary argument for the semantic Web.

New OSF Platform Leapfrogs Earlier Releases in Features and Capabilities

New OSF Platform Leapfrogs Earlier Releases in Features and Capabilities