The Structured Web is But an Early Hurdle to the Semantic Web

About a year ago (May 30, 2006), Dr. Douglas Lenat, the president and CEO of Cycorp, Inc., gave a great talk at Google called Computers Versus Common Sense. Doug, a former professor at Stanford and Carnegie Mellon, has been working in artificial intelligence and machine learning his entire career. Since 1984 he has been working on the project Cyc, which subsequently formed the basis for starting Cycorp in 1994. Cycorp, as may become apparent below, does much work for the defense and intelligence communities.

Google Research selected this 70-min video as one of its best of 2006, and I have to heartily concur. Doug is very informative and is also an an entertaining and humorous speaker.

But that is not the main reason for my recommendation. For what Doug presents in this video are some of the real common sense challenges of semantic matching and reasoning by computer. These are the threshold hurdles of intelligent agents and real-time answering and (perhaps) forecasting, the ultimate objectives that some equate to the “Semantic Web” (title case):

Because of the reasoning objectives Cycorp and its clients have set for the system, threshold conditions require not only more direct deductive reasoning (logical inference from known facts or premises), but also inductive (inferred based on the likelihood or belief of multiple assertions) and even abductive reasoning (likely or most probabilistic explanation or hypothesis given available facts or assertions). Doug makes clear the devilishly difficult challenges of determining semantic relevance when complete machine-based reasoning is an objective.

As I listened to the video, I interpreted the attempt to reach these objectives as bringing at least four major, and linked, design implications.

As I listened to the video, I interpreted the attempt to reach these objectives as bringing at least four major, and linked, design implications.

The first design implication is that the reasoning basis requires many facts and assertions about the world, the basis of the “common sense” in the knowledge base. An early lesson that some AI practitioners in the “common sense” camp came to hold was that learning systems that did not know much, could not learn much. When Cyc was started more than 20 years ago, Lenat and Marvin Minsky estimated on the back of an envelope that it would take on the order of 1000 person-years to create a knowledge base with sufficient world knowledge to enable meaningful reasoning thereafter. This is what Lenat has called “priming the pump” of the knowledge base with common sense to resolve so many classes of semantic and contextual ambiguities.

However, this large number of assertions has a second design implication, if I understood Lenat correctly, for the need for higher-order predicate calculus. These higher orders for quantification over subsets and relations or even relations over relations are designed to reduce the number of potential “facts” that need to be queried for certain questions. This makes the knowledge base (KB) as a whole more computationally tractable, and able to provide second or sub-second response times.

A third implication is that, again to maintain computational tractability, reasoning should be local (with local ontologies) and with specialized reasoning modules. Today, Cyc has more than 1000 such modules and reasoning in some local areas may not actually infer correctly across the global KB. Lenat likens this to the observation that local geography appears flat even though we know the entire Earth is a globe. This enables local simplifications to make the inferences and reasoning tractable.

Finally, the fourth implication is a very much larger number of predicates than in other knowledge bases or ontologies, actually more than 16,000 in the current Cyc KB. This large number comes about because of:

- simplifying some of the more complex expressions that frequently repeat themselves in some of the higher-order patterns noted above as new predicates, again to speed processing time, and

- providing more precise meanings to certain language verbs that humans can disambiguate because of context, but which pose problems to computer processing. For example, Cyc contains 23 different predicates relating to the word “in”.

Growing the Knowledge Base

Roughly about the year 2000, sufficient “pump priming” had taken place such that Cyc could itself be used to extend its knowledge base through machine learning. A couple of critical enablers for this process were the querying of Web search engines and the engagement of volunteers and others to test the reasonableness of new assertions for addition to the KB. The basic learning and expansion process is now generally:

formal predicate calculus language -> natural language queries -> issue to Web search engine -> translate results back to predicate language -> present inferences for human review -> accept / reject result (50%) ->’ add to KB (knowledge base)

The engagement of volunteers is also coming about through the use of online “games”. Open source (see below) is another recent tool. (BTW, the 50% acceptance rate is not that there are so many wrong “facts” on the Web, but that context, humor, sarcasm or effect can be used in human language that does not actually lead to a “correct” common-sense assertion. Such observations do give pause to unbounded information extraction.)

Thus, today, Cyc has grown to have a very significant scope, as some of these metrics indicate:

- 16,000 predicates

- 1,000 reasoning modules

- 300,000 concepts

- 4,000 physical devices

- 400 event-participant relationships

- 11,000 event types

- 171,000 “names” (chemicals, persons, places, etc.)

- 1,100 geospatial classes, 500 goespatial predicates

- 3.2 million assertions

As might be expected, the overall KB continues to grow, and on an accelerating rate.

Threshold Conditions and the Structured Web

This all appears daunting. And, when viewed through the lens of the decades to get the knowledge base to this scale and in terms of the ambitiousness of its objectives, it is.

But semantic advantage and the semantic Web is not an either/or proposition. It is a spectrum of use and benefit, with Cyc representing a relatively extreme end of that spectrum.

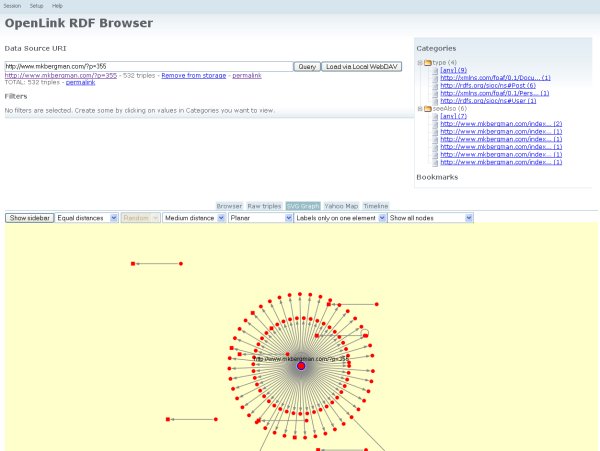

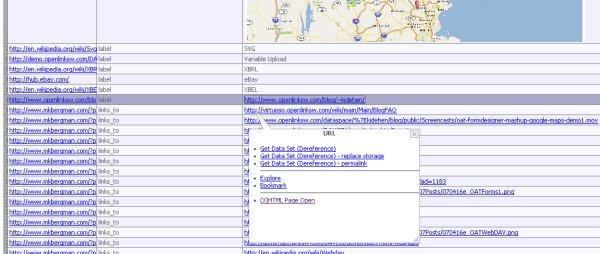

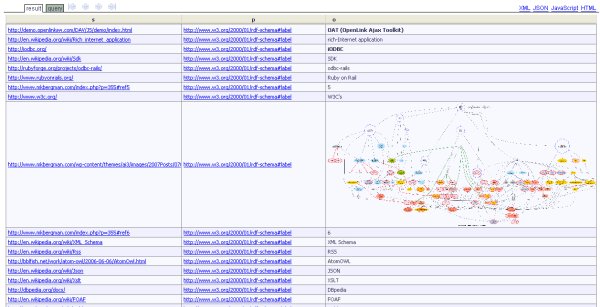

In my recent post on Structurizing the Web with RDF, I noted a number of key areas in which the structured Web would bring benefit, including more targeted, filtered search results, better results presentation, and the ability to search on objects and entities not simply documents. Structurizing the Web, short of full reasoning, is both an essential first step and will bring its own significant benefits.

The use of RDF is also not unnecessarily limiting compared to Cyc’s internal predicate calculus language. The subject–predicate–object “triple” of RDF and its reliance on first-order logic for deduced inferences can also be used to express propositions about nested contexts resulting in metalanguages for modal and higher-order logic. OWL itself is expressed as a metalanguage of RDF encoded in XML; and virtually all mathematics can be described through RDF.

Thus, Cyc, like DBPedia and related efforts to express Wikipedia as RDF, can itself be a rich source of structure for this evolving Web. Like other formats and frameworks, parts can be used in greater or lesser scope and complexity depending on circumstances. The sheer scope of Cyc’s world view in its knowledge base is a tremendous asset.

OpenCyc as a Useful Knowledge Base

The value of this asset increased enormously with the release of OpenCyc in early 2002. The OpenCyc knowledge base and APIs are available under the Apache License. There are presently about 100,000 users of this open source KB, which has the same ontology as the commercial Cyc, but is limited to about 1 million assertions. The most recent release is v. 1.02. An OWL version is also available. The Cyc Foundation has also been formed to help promote further extensions and development around OpenCyc.

There has been some hint on the OpenCyc mailing list of others interested in creating RDF versions of OpenCyc or portions thereof, with the similar benefits to RDF versions of Wikipedia via SPARQL endpoints and retrievals, mashups and RDF browsing. OpenCyc would also obviously be a tremendous boon to better inferencing for the datasets that are rapidly becoming exposed via RDF.

The idea of the local ontologies and reasoners that Lenat discusses — and the broader collaboration mechanisms emerging around other semantic Web issues and tools — bode well for a resurgence of interest in Cyc. After more than two decades, perhaps its time has truly come.

BTW, some interesting slides with pretty good overlap with Lenat’s Google talk can be found here from the Cyc Foundation.

In response to my

In response to my