Part 3 in the Enterprise-scale Semantic Systems Series

Part 3 in the Enterprise-scale Semantic Systems Series

The interests of enterprise architects and semantic technologists do not align. An enterprise architect has the viewpoint of the enterprise and its full breadth of IT requirements, from security to access to content and maintainability (all of which needs to be justified to non-IT managers). The semantic technologist tends to view his entire world through the lens of semantic technologies.

If one is a resident within the semantic technology community, more often than not today’s assessment is that semantics have yet to be successful. If the deployment somehow does not have semantic technologies front and center, then it is largely invisible. The fact that semantic technologies are the core enablers from initiatives ranging from Siri to Pandora to Google and recommendation engines is not embraced and credited: the semantic contribution is hidden.

If one is an enterprise architect, the primacy of whether semantic technologies are in play or not is a non-issue. There are many piece parts to be fulfilled; the system and overall architecture are the concern, not any individual component. The architecture must be broken apart, with the assessment of the suitability of any individual component not based solely on its standalone capabilities, but also as part of an inter-operating whole.

Semantic technology has generally not penetrated well into the enterprise (though it sometimes has in some of the consumer plays as noted above) because its advocates (and, therefore, deployers) have not understood its role. Sometimes semantic technologies are visible, but, more often than not, they are not. The natural role of semantic technologies is in content and schema mediation, functions which reside generally at the repository level and not that of the user.

Two rending forces arise from the wrongful perception that somehow semantic technologies must be evident. The first dissonance is that semantic advocates are often indiscriminate in where they focus their advocacies. While semantic approaches can, theoretically, be applied from the user content management level to applications, these are neither the pain points nor the focus of enterprise architects. EAs are interested in semantic technologies for content integration and interoperability, as often evidenced by superior search, not other uses. The second dissonance is that, not recognizing its natural role, semantic technologists are not paying attention to making their capabilities inter-operable with the rest of the enterprise stack.

Actual enterprise deployments have a rhythm and hierarchy of scrutiny and decision-making. For semantics to become an integral contributor to enterprise solutions, it is important to recognize where this function can fit today. There should be no arrogance in this discussion whatsoever. Like a Galileo thermometer, it is important to find the natural resting point for semantic contributions . . . .

A Basic Architecture

As other discussions by Fred Giasson and I have put forward, the nature of our (Structured Dynamics) semantic stack, what we call the open semantic framework (OSF), has Drupal as its resident content management piece, with Virtuoso the RDF triple store, and many additional open source parts. Our TechWiki explains more of that in detail.

The OSF architecture, though, is generalized enough such that these two components, or any of the other open source pieces in the stack, could be swapped out for others. It is the Web service glue underneath OSF, SD’s structWSF framework, that is the real enabler of the entire semantic stack.

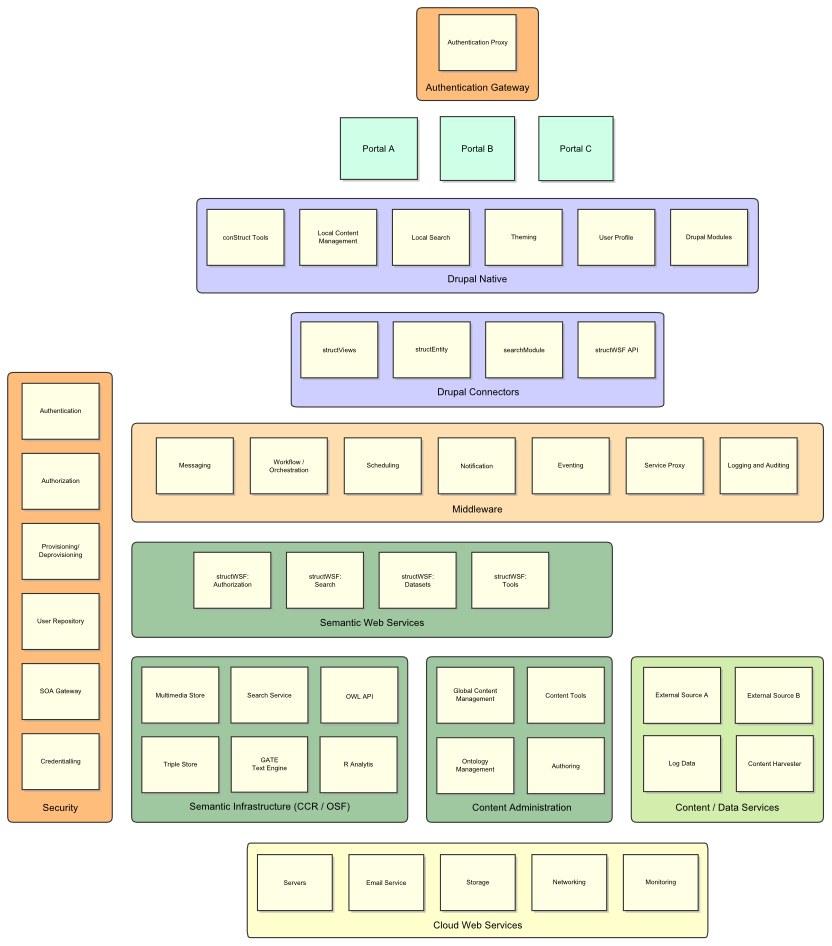

Yet when one is done with design of an enterprise architecture, the actual semantic portion (shown in green below) becomes itself a mere component, all embedded into the full suite of enterprise requirements. This illustrative architecture, generalized across clients, again uses Drupal as the content management framework, with the new service being hosted in the cloud:

We see that a security component now governs all interactions. Middleware has been inserted into the standard OSF stack (Drupal + semantic services) and now takes over the functions of logging, messenging, an enterprise service bus, security, and version control and data governance things. All of our hardware, network services, and Web servers are provided in the cloud. We also need to conform to existing content and data sources and the means to harvest or get updates from them.

The semantic component — OSF in our case — has in effect been surrounded by existing or external sources and services. The semantic management responsibility resides at the core of this architecture, thus making the content repository very important. But, in order for the repository to perform its work, it must interface with all of these existing and required systems. In order for semantics to make enterprise contributions, it must become, in effect, a “hidden” or “buried” service.

When targeting enterprise customers, this role for semantic technologies is a reality. For systems to be adopted, which is the first step to being effective, it is helpful to warmly embrace that your installation will be as much involved with interfaces and external sources and systems as much as semantics alone. Embracing this viewpoint means you are being adopted.

This reality does place a premium on a Web service architecture for the semantic stack. All endpoints can be communicated with via HTTP, and all endpoints have a common and published API. Each re-factoring stresses making the interfaces distinct and clean, and embracing common syntax and protocols for communicating with the endpoints.

The Natural Resting Place for Semantic Technologies

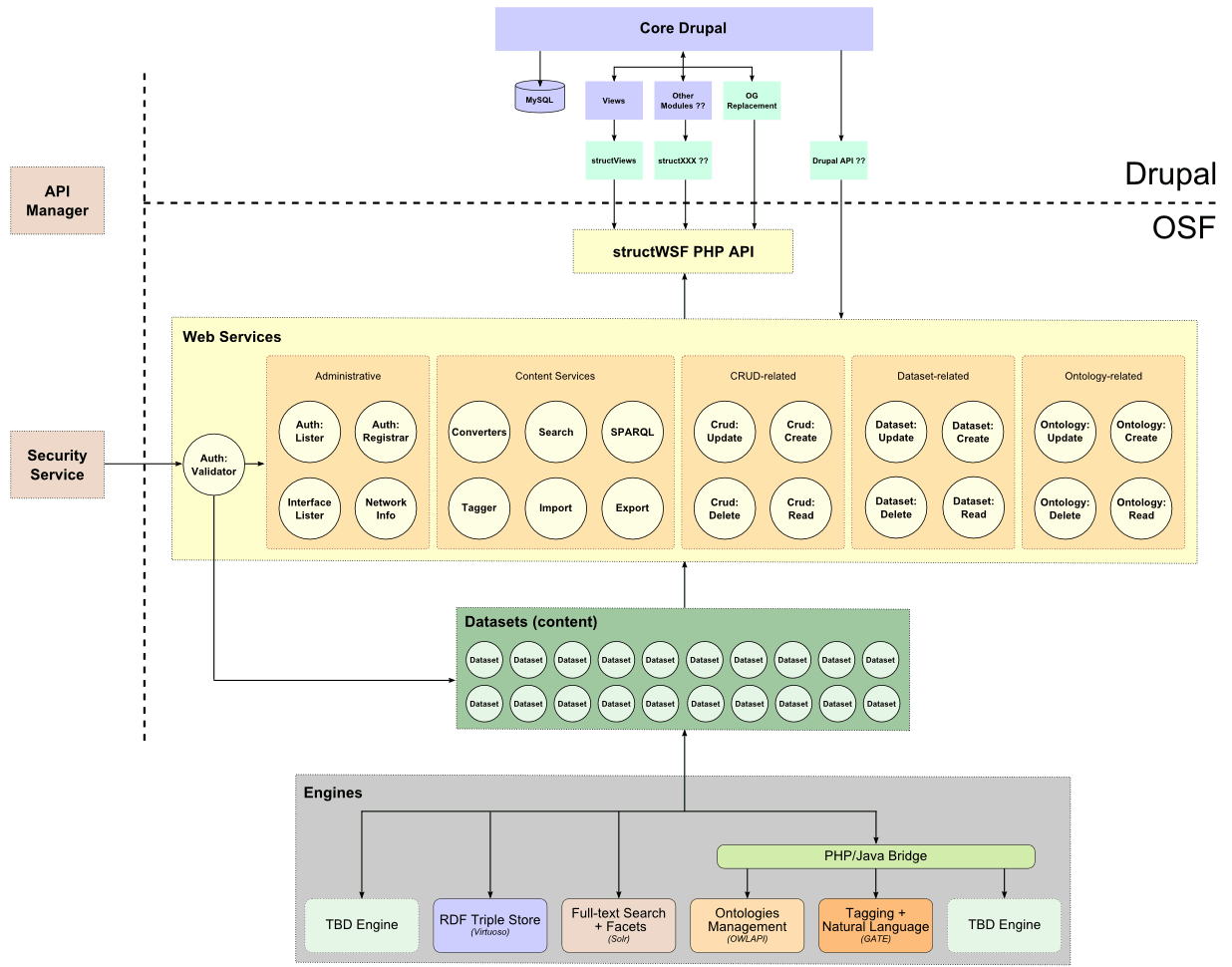

We can expand the green portion of the diagram above — the semantic components or what corresponds to OSF — and show them in more detail, as in the next architecture diagram below. We are now enumerating the Web services in the stack, and are showing the interaction with datasets (important for the security aspects, which a later installment of this series will address). The various engines that power the OSF stack are shown at bottom:

While it is true that the semantic components are “buried” within all portions of the enterprise stack, we can ease the integration challenge by narrowing the interface points to the non-semantic portions. At the top level, in the interaction with the content management framework (Drupal in our case), we have aggregated all Web service interface calls and made them available via a programmatic API via the structWSF PHP API. (Multiples of these can be developed if the programmatic interfaces need to be in languages other than PHP, such as Java.)

The structWSF API provides a consolidated point for writing endpoint calls and queries using PHP. This not only makes it more efficient for developing endpoint connectors (whose purpose is to enable Drupal methods and modules for interfacing with the repository), but also provides a common API and methods. Though it is possible to issue queries directly to any structWSF Web service endpoint, the structWSF API module is a faster and more consistent interface for doing so. This consolidation also means that developers interacting with the semantic components need only worry about the dedicated API module, and not the code or location in the more than 20 individual endpoints.

A similar philosophy is applied to narrowing the security interfaces. We treat security as a black box. Granting access and rights is proxied at the middleware layer. If these rights are granted, the query payload is presented to the Auth:Validator endpoint via a registered security gateway IP. The verification of the IP by Auth:Validator enables the query to be submitted, with a results set also returned via the same pathway.

Three design mindsets govern this architectural design. First, interface points are narrowed and standardized, generally with a formal API. Second, important external services are treated as “black boxes”; how they do their work is immaterial. Only vetted requests and calls approved at these other layers are able or authorized to access the services at the semantic layer. And, third, we are not trying to embrace non-semantic functionality at the semantic layer. These important services — but ancillary ones from a semantic standpoint — are understood as being out of scope to the semantic requirements. This design also makes it easier to “plug” the semantic components into other enterprise stack configurations with other non-semantic services from other sources or vendors.

Some Development Gaps and Imperatives

This design makes sense from a theoretical standpoint, but can pose problems in practice.

The first challenge is that our OSF approach is based on RESTful Web services, in a true Web-oriented architecture. Many of the non-semantic legacy components were originally designed for formal big WS-* approaches drawn from the SOAP perspective. Though most of these existing interfaces have evolved to embrace RESTful alternatives, these interfaces are not always as well tested and complete as the original WS-* ones. This relative immaturity can pose issues with respect to completeness of parameter or function support or inadequate testing.

A second challenge, also related to a RESTful Web service perspective, is the size of payloads in both query and results set objects. Long HTTP queries with many parameter requests and large results sets can be a problem to handle, especially in the security layer. In some cases, we have had to look at ways to minimize and package (consolidate) parameter options in order to make endpoint requests more efficient.

Encoding mismatches are a further challenge. It is generally best, for example, to adhere to a standard UTF-8 encoding via all semantic component interfaces. This requires attention and coordination on both sides of the interface.

The more fundamental challenge, however, is one of mindset. Effective interfaces require effective communications of the participating vendors across the boundary. The terminology, concepts, logic and open-world approach of semantic technologies are not easily communicated to nor immediately understood by traditional practitioners. The communications must be constantly worked in order to overcome past practices and embrace the flexibilities provided by semantic technologies.

The Mismatch is Not Long-term

But these challenges are more one of degree and practice than anything more fundamental. As semantic components get deployed in an enterprise stack, the benefits of faceting and the underlying structure become apparent. Such awareness propels further understanding and a willingness to learn more about underlying foundations. Ultimately, with a design emphasizing a relatively few, focused interfaces, semantic components can be effectively integrated within enterprise stacks.

The more telling lesson is the understanding of the natural role that semantic technologies play within enterprise-scale systems. Semantic technologies are the natural integration framework for federating and interoperating virtually any and all non-transaction information assets of the enterprise. That places semantic technologies at the core of the enterprise stack, even if it is not terribly evident to all users. The natural role for semantic technologies for the nearest term appears to be in repositories and for content integration.